Can new federal plan really bring high-speed rail to Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor?

Taking them might beat driving, but trains on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (NEC) are not very fast. It takes about an hour and fifteen minutes to get to New York from Philadelphia on the Acela Express, Amtrak’s so-called high speed option. That speed is closer to those of the legacy trains of yore than the modern, high-speed rail prevalent across Europe and East Asia. Real high-speed rail along the NEC would link Philadelphia to New York in less than 40 minutes and to Washington, D.C. in less than an hour.

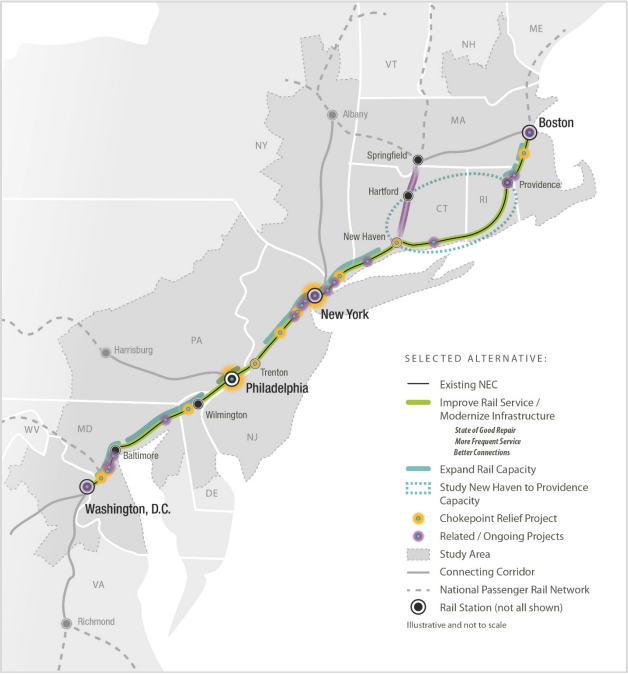

In support of the goal of high-speed rail, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) began a program called NEC Future, which examined alternatives for improving the corridor.

Unfortunately, the FRA may have compromised NEC Future in two ways. First, it didn’t consider each potential speed upgrade to the corridor separately. Instead of evaluating each separate infrastructure proposal for cost-effectiveness, it analyzed three consolidated scenarios with different levels of investment. Second, even the lowest-investment scenario included many projects whose benefits accrue almost entirely to commuter rail—think SEPTA’s Regional Rail or, really, NJ Transit. It packaged these projects under the umbrella of NEC Future, but they are not really about the future of the intercity NEC, but about the future of intra-regional commuter rail in Boston, Washington, and New York.

Of the three alternatives it studied, the FRA just announced its preferred set of options and recommend the middle option, which would reduce travel time from Philadelphia to New York to about 50 minutes and overall travel time from Boston to Washington to five hours. The estimated cost: $121 to $153 billion. It is possible that the majority of this pricetag would consist of commuter rail improvements rather than speed boosts.

The biggest single item NEC Future proposes is the Gateway Project, which would build a new tunnel between New York City’s Penn Station and New Jersey and install related capacity upgrades costing about $28-29 billion. Other large commuter rail upgrades in the plan include a $2 billion expansion of Boston’s South Station and a $7 billion upgrade to Washington’s Union Station. While regional commuters in these metro areas may welcome these improvements—although some face local opposition—they won’t do anything to speed up trips between cities.

The primary selling point of Gateway is capacity. Right now, Amtrak runs between two and four trains from Philadelphia to New York during peak hours. When it runs four trains, two are Regionals (regular service running at lower speed making more stops between Boston and DC), one is an Acela Express, and one is a Keystone (running between NYC and Harrisburg by way of Philadelphia). Amtrak can’t run any more than four trains in the tunnels underneath the Hudson River without taking spots currently used by New York commuter rail , but commuter trains from North Jersey to Manhattan are already packed well beyond seated capacity. By adding the new Gateway tunnel, NEC Future would allow Amtrak to on run ten trains per hour during peak between Philadelphia and New York.

However, there are cheaper ways to add capacity—if not as much as NEC Future would like— than building pricey, new tunnels. The easiest is to just run longer trains. All of the intercity rail platforms between New York and Washington are long enough for 12-car trains, and some can fit 16 cars (except Wilmington, which can fit 11 cars). But trains on the NEC run, at most, eight-car trains, which includes a locomotive (two on Acela trains) and a cafe car, meaning only five or six cars are dedicated to passenger seating. And most, if not all, of the platforms that can’t already fit 16 cars could be lengthened at relatively low cost. The six-car Acela (of which one car is a cafe) has about 300 seats. A 16-car Japanese bullet train, with the same roomy seats as Amtrak, has about 1,100.

During the early stages of NEC Future planning, there were calls for building a new Amtrak tunnel under Center City dedicated to high-speed trains that would have served Market East Station, instead of 30th Street Station. There was no support for this tunnel in Philadelphia, so the NEC Future planners dropped it. This decision wasn’t merely political: The tunnel would have been very expensive for the amount of time it would have saved on intercity travel times, with no ancillary benefits for Regional Rail. Meanwhile, other expensive urban projects, including Gateway, remain in NEC Future’s plans because they benefit commuter rail as well as intercity travel times, and enjoy more local political support.

But even within the scope of intercity rail improvements, the priorities are not always in order of maximum reduction of travel time for the highest number of passengers at minimum cost. A source who worked for one of the private consultants involved in the NEC Future planning explained to PlanPhilly how the FRA came up with the alternatives.

Per the FRA’s plan, the NEC Future alternatives analysis included three main options, in increasing order of costs and benefits numbered 1-3. Alternative 1 just featured incremental improvements and fixes to the worst slowdowns (for example, trains must reduce speed to 30 miles-per-hour at the Shell Interlocking near New Rochelle, New York, which is kind of like having I-95 drop down to 20 mph when it runs through Chester). The most expensive option, Alternative 3, included full high-speed rail with dedicated tracks the entire way between DC and Boston, putting Philadelphia not much more than an half hour away from New York and less than an hour from Washington. In the end, FRA played Goldilocks and picked the in between option, Alternative 2 which would put Philadelphia 1:15 from Washington and perhaps 50 minutes from New York.

According to a consultant on the NEC Future plan who spoke anonymously because they were unauthorized to comment on the planning process, the project was set up in a way that prevented planners from considering that the best alternative may differ in each segment. In other words, they never thought to mix-and-match different elements from the three options. In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the corridor is largely straight (except for a short stretch through Providence, RI and its suburbs). The average Acela speed is already fairly high, which means the low-cost Alternative 1 might have been the most appropriate option for this section. But more work is required around Philadelphia, so Alternative 2 may offer more bang for the taxpayer buck. In Connecticut, where the curvy and slow tracks need the most work to improve speeds, Alternative 3 may have been best.

Sticking to just Alternative 2 also means that the FRA will skip some easy fixes to significantly increase speeds along certain stretches of the Northeast Corridor. Between Newark, NJ and Philadelphia, the Corridor is mostly straight, with just a few short, sharp curves between otherwise fast segments (most notably in Elizabeth and around Metropark). Straightening those curves, even with some minor residential and commercial takings, would enable very high speeds from Newark to the Philadelphia suburbs. But this didn’t make it into the FRA’s final NEC Future plan. That’s because Alternative 2 aims for a top speed of 160 mph, making the slowdowns to 100 mph restrictions around these curves not a big deal. But if the FRA was aiming to increase maximum speeds to 220 mph, those restrictions would become much worse, because the hitting the brakes down to 100 mph and then accelerating back up to 220 mph would take so much longer.

The stretches of track near city stations offer the biggest speed boosts per mile of track rebuilt. The old interlockings at a complex city stations—like 30th Street Station or Penn Station in New York, where dozens of separate lines converge leading into the terminals—can add two minutes of travel time within sight of the platforms. Some fixes are cheap. A mile and a half north of 30th Street Station, the Main Line and NEC tracks diverge at Zoo Junction, and the NEC has one of its tightest curves, currently limited to 30 mph. However, if the tracks were properly banked along the curve, Acela trains could navigate them at 70 mph. Other fixes may be unaffordably expensive, such as those that would require modifying the support columns at underground stations. But NEC Future does not provide a good list of which individual fixes are cheap and which are expensive, because it only considered the three alternatives as wholes.

It is likely that a project aimed at maximizing speed increase per dollar invested could create benefits approaching those of full high-speed rail. The New York-to-Philadelphia segment in particular needs some curve fixes, even with some takings, but no new tunnels or greenfield alignments. Even the complicated curve at Frankford Junction, currently limiting trains to 50 mph, could probably be straightened to 110-125 mph for $150-250 million.

The ultimate goal should be to construct high-speed rail averaging about 150 mph, on par with trains in Europe and East Asia. This would put Philadelphia about 38 minutes from New York, 56 minutes from Washington, and perhaps 2:15 from Boston. NEC Future is on the way to this goal, with many useful projects that will support higher speeds. But a more flexible investment strategy that mixed low-end and high-end investments, could provide faster travels times at lower costs.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.