Camden’s past reflected clearly in exhibit; artistic future remains uncertain

-

The Thomas Jefferson Hospital Center for Urban Health, working with the Restaurant Opportunities Center of Philadelphia, is providing free flu shots for restaurant workers. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Thomas Jefferson nurse Clarissa Knight injects Teo Reyes with a flu shot. The Thomas Jefferson Hospital Center for Urban Health, working with the Restaurant Opportunities Center of Philadelphia, is providing free flu shots for restaurant workers. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Thomas Jefferson nurse Clarissa Knight injects Diana Allinger with flu vaccine during a free clinic for restaurant workers at Thomas Jefferson Hospital Center for Urban Health. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Thomas Jefferson nurse Clarissa Knight injects Diana Allinger with flu vaccine during a free clinic for restaurant workers at Thomas Jefferson Hospital Center for Urban Health. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

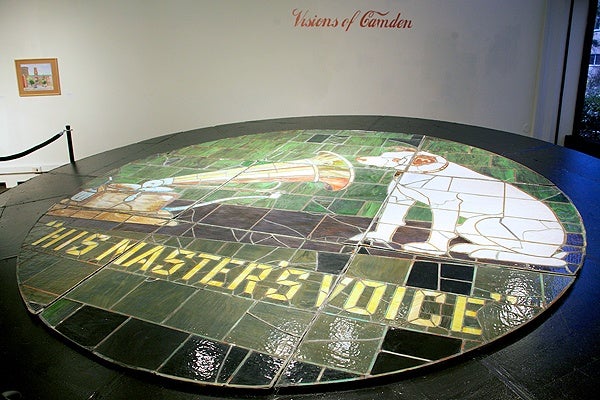

<p>One of four stained glass windows once in the Nipper building's tower. The trademark was originally installed in 1915 and was illuminated at night. (Nat Hamilton/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

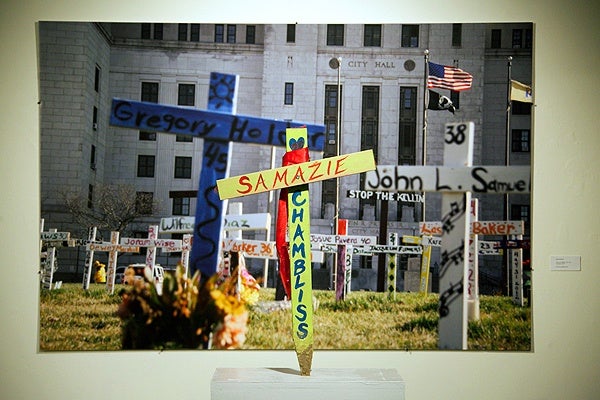

<p>Ken Hohing, Untitled 2012, digital photograph. The work dramatizes the impact of gun violence in Camden, N.J., as part of the Visions of Camden exhibition.</p>

-

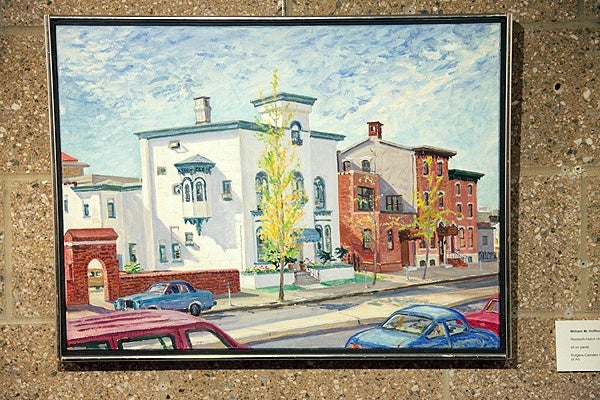

<p>William M. Hoffman, Reinboth-Hatch House, 1991, oil on board. The building is no longer standing. (Nat Hamilton/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

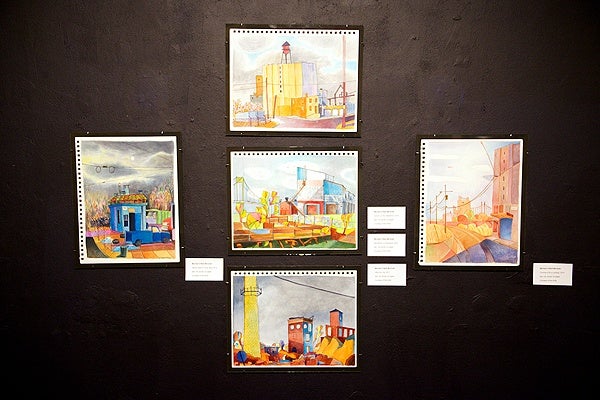

<p>Mickey McGrath's artwork, on display at the Sedman Gallery. (Nat Hamilton/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Cyril Reade is one of the curators for Visions of Camden, at the Stedman Gallery at Rutgers University in Camden. (Nat Hamilton/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>“This Stedman Gallery exhibition offers – and invites – insights into Camden’s past, its present, and its prospects,” says Cyril Reade, curator for the Visions of Camden exhibit. (Nat Hamilton/for NewsWorks)</p>

-

<p>Mickey McGrath's studio, in South Camden N.J.</p>

-

<p>The Rev. Mickey McGrath, <span style="font-family: Arial, Helvetica, Verdana, 'Bitstream Vera Sans', sans-serif; font-size: 12px; line-height: 18px;">Oblate of St. Francis de Sales, </span>is among the artists in a show highlighting art in Camden, N.J. (Nat Hamilton/for NewsWorks)</p>

“I’m a half-full kind of guy,” says Cyril Reade, the director for the Center of Art on the Rutgers-Camden campus. The recent transplant co-curated “Visions of Camden,” an exhibition of art and artifacts of a once-grand city.

“Camden was really a very prosperous town, and really worked in tandem with Philadelphia,” said Reade. “There’s Cooper’s Ferry, Cooper’s Landing. RCA Victor was here, and Campbell’s soup. There’s the shipyards. There’s this incredible history.

“And just seeing development in a lot of places — there has been a spark,” he said. “There’s no reason to not foresee something happening here.”

The exhibition’s showstopper is an enormous, 16-foot diameter, stained-glass window depicting a dog listening to a record player: Nipper hearing “his master’s voice.” One of the original windows from the iconic RCA building is bathed in music as RCA recordings from the early 20th century are piped into the gallery as mp3 tracks.

The show, at the Stedman Gallery until March, also includes archival photo documentation of the building of the Ben Franklin Bridge, vintage Campbell’s soup advertisements featuring images of Camden processing plants, wooden crosses that had been planted outside City Hall marking the city’s homicide rate (with dirt still clinging to their spikes), and cityscapes by local artists.

The holy and the wholly Camden

One of those artists is Brother Mickey McGrath, a Catholic oblate and the resident artist of the Sacred Heart Church in South Camden. He primarily works in religious subject matter, but almost every morning he takes a meditative walk around the Camden waterfront.

“Coming down Second Street, as I do every day, I see all these warehouses and factories,” said McGrath in his South Camden studio. “I can’t help but think of, not only the shapes themselves, but the generations of people that worked there. The families that lived in this neighborhood.”

While his religious paintings are large canvases reflecting biblical narratives, the small acrylic cityscapes on display at Rutgers-Camden were literally ripped from his sketchbook — perforated edges torn from the book binding can still be seen.

“They’re more than a diversion. I don’t see them differently from the religious stuff,” said McGrath. “When I’m painting them, I get caught up in the same contemplative, peaceful moment as I do whether it’s an icon of a Madonna. It’s all good.”

A dearth of artists

McGrath is one of the very few full-time artists working in Camden, there by the invitation of Sacred Heart Church, which bought and renovated the rowhouse that became his studio.

Despite the surplus of abandoned buildings, artists have steered clear of Camden.

“In a lot of places that I lived, artists have gone into abandoned parts of the city, and occupied it. Then the graphic designers come, and the boutiques,” said Reade. “How can you have an area that is so close to Philadelphia, half if not a third of the cost of Philadelphia, to be a no-man’s land?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.