Brujo’s departure an artistic loss for Philadelphia

As one of the 11 million immigrants who came to this country illegally, he has grown weary of the endless threat of deportation, a risk that's skyrocketed under Donald Trump.

-

Brujo de la Mancha is the founder of Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac, which aims to bring indigenous culture and history to the Pa. community. Brujo dances in celebration of Indigenous Peoples Day in October of 2013. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Brujo De La Mancha teaches ceramics to kids at Taller Puertorriqueño. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

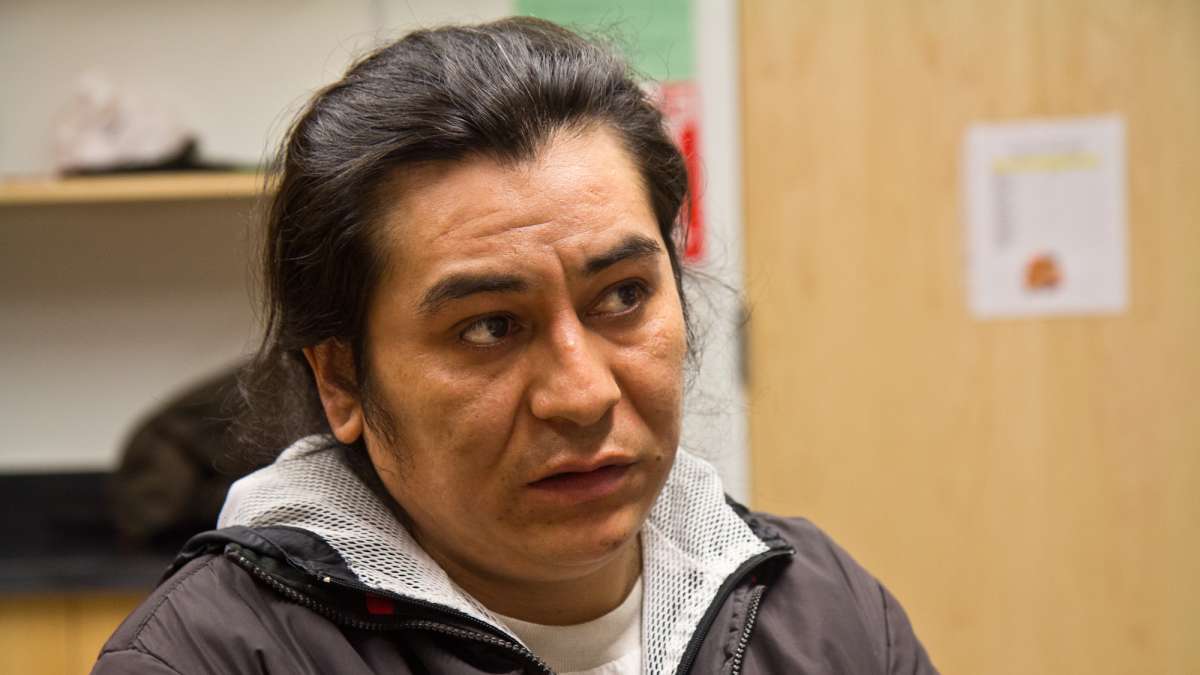

Brujo De La Mancha came into the United States from Mexico 19 years-ago. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Sculptures created by the students of immigrant artist Brujo De La Mancha. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Brujo with Pa. governor Tom Wolf. (Photo by Jesica Diaz)

Brujo de la Mancha is a man whose roots run deep in the community.

He’s an artist, teacher and performer who has done so much in Philadelphia that his resume rambles on for four pages. Philadelphia officials honored him with an “Unsung Hero” award for his work with troubled kids, and he was named one of Delaware Valley’s Most Influential Latinos in 2013.

But Brujo is done with Philadelphia. In fact, he’s done with the United States, altogether.

As one of the 11 million immigrants who came to this country illegally, he has grown weary of the endless threat of deportation, a risk that skyrocketed with Donald Trump’s election to the White House.

He doesn’t want to hunker down until he can get legal documentation — or more immigration-friendly leaders take office — as so many other unauthorized immigrants have decided to do. He knows that could take years to happen — and might never happen at all. He’s lost track of how much money he’s already spent on immigration attorneys who couldn’t help him.

So he wants to move to Canada. He plans to take an English test later this week to prove his proficiency, the first step in the months-long visa-application process. If all goes well, he hopes to be living — legally — in the Great White North by this summer.

“The goal will be to be free, because I have not (felt) free for so long,” Brujo said. “It creates some type of mental problem to be here for so long (with) no hope. It’s like a desperation. It’s like a ghost. I can’t go anywhere else. I wake up (each day), I look around my house, and I think: ‘Everything is a dream! Everything is fake! Nothing here is yours. Nothing is real.’”

Brujo, now 39, grew up in a poor, gritty neighborhood in Mexico City, tormented “by machos” because of both his indigenous Mexican heritage in the Tlaxcalan tribe and his long-haired, punk-rocker look, he said.

At 17, he joined activists rallying in Mexico City to mark 2 de Octubre, an annual commemoration of the authoritarian government’s 1968 massacre of students protesting repression and violence.

That was the first time he got arrested. Police made him squat for hours, kicking him whenever he moved, before freeing him, he said. The next few years brought more baseless arrests at the hands of cops quick to crack down on dissidents, he said.

“They were hard times where the police was undercover, militaries, persecutions,” he said. “You look or dress radical at the time, they will stop you for anything. Mostly they do it because they want to scare you, so you don’t do that thing again. They don’t want you to think outside the box.”

Brujo moved around Mexico to escape the violence, but met an American woman in 1997 in Oaxaca City who loaned him money to leave Mexico. So in February 1998, he paid a man $750 to join a group of about 20 people who journeyed on foot across a treacherous mountain pass called La Rumorosa to get into southern California.

“After three and a half days of walking, I could not walk anymore,” Brujo said. The group stopped briefly at a rural church, where they washed up and ate, before Brujo paid $300 for a taxi to take him to the Los Angeles area. He then traveled further north to San Francisco, where he had friends. But when his American friend, who lived in Philadelphia, again offered him money to relocate to Philly, he accepted without hesitating.

“I wanted to learn English, and my friends in California did not know English,” he said. “So I said: ‘I need to go.’”

The ride, on a Greyhound bus, took three days. The view out the window was eye-opening. During a rest stop in Utah, he marveled at the computers he saw in a trash bin.

“It was very knocking on my head to see a lot of good things in the trash, because in Mexico, we fix a lot of things, fix it and sell it again,” he said.

In Philadelphia, he discovered that far bigger things than computers were trashed.

“There was a lot of abandoned houses, a lot of empty buildings,” Brujo remembered. “I was like: ‘Wait a minute, did they have a war here and never fix it?’“

Brujo spent his first six months or so in Philadelphia living as a squatter in one of those abandoned houses, until police kicked him out.

“But that place is still abandoned, up to now,” Brujo said recently. “I see United States as wasting, wasting, wasting, and wasting.”

Brujo began working in West Philadelphia’s punk scene as a musician but also learned to paint, sculpt, draw, and dance, all of it flavored by his indigenous Mexican roots and his passion for repurposing discarded objects.

His talent earned him space on some pretty prestigious stages, including the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

It also drove him to teach, both as a way to share his indigenous heritage and a means to support himself. He has taught art everywhere from Taller Puertorriqueño and the Fleisher Art Memorial to Rutgers University and the Please Touch Museum.

He arguably might be best known for his work with Ollin Yoliztli Calmecac, the Aztec dance troupe and cultural group he cofounded in 2003.

“He doesn’t sit still for long,” laughed Gina Renzi, director of The Rotunda in University City, where Brujo was the artist-in-residence in 2014.

Renzi created an online “Save Brujo” fundraising campaign and will host a fundraising dinner and concert at The Rotunda to help cover the costs of his move to Canada.

“I wish he didn’t have to leave, but at least we can help him leave safely,” Renzi said.

Of his departure, she added: “It’s a pretty big loss. He is this really interesting cultural connector and educator. Philly is a diverse city, but like any other place, people really are separated in these boxes. Brujo has found this way to transcend communities, from the Puerto Rican community to Native Americans, from kids to seniors. And there really isn’t that much in Philly for indigenous people — there isn’t even a community center. But he has remained present in all of that work. For him to leave, it’s a big deal culturally and for folks in the creative sector.”

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Brujo is one of about 150 artists and community members now working on Philadelphia Assembled, a resilience-themed project involving citywide performances, events and installations starting this month.

“His voice truly does stand out in that he is really able to thoughtfully address subjects of forced migration,” said Amanda Sroka, assistant curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “These subjects are incredibly present in both his artworks, his paintings, but also in the way he holds and builds relationships across Philadelphia. That is something that we all, especially in this moment in time, need to be thinking about and addressing in our own work and our own practices.”

Brujo’s plight as an unauthorized immigrant isn’t unusual, but his decision to ditch the United States and head north is, said Carlos Torres, a spokesman for the Mexican Consulate in Philadelphia.

More often, Mexicans fearful of deportation have come to the consulate seeking answers and paperwork that would enable them to stay here — or return to Mexico, Torres said. Since Trump took power, the number of Mexicans visiting the consulate for passports and other help has doubled, from about 200 to up to 400 daily, he said. About 133,000 people who were born in Mexico now live in Pennsylvania, including 40,000 in the Philadelphia region – although it’s unclear how many are undocumented, Torres said.

Brujo doesn’t want to move back to Mexico, still plagued by fears of the troubles he endured as a teenager there.

He knows going public with his plight could put him in deeper danger of deportation. For that reason, he doesn’t use his birth name; Brujo (sorcerer) de la Mancha (a nod to both the Spanish region and the Don Quixote tale) is the pseudonym he has used as an artist for almost two decades.

But he also has reached a point of resignation.

“I leaving, what else you want to do now, you want to spend the money to take me to the border? You’re going to spend all that? Go ahead! I leaving!” Brujo said.

Besides, he added: “The FBI knows where I am because (they took) my fingerprints to work in the schools.”

If he’s successful in securing a Canadian passport, the first thing he aims to do might seem surprising: visit Mexico.

“I have not seen my dad for almost 20 years,” he said. “I feel the sadness of my friends (here) when I tell them I will go, but I also feel a little bit happiness. It’s tough for me to be in Mexico, but I got to go and see my dad. It’s a moral principle. Anybody should be allowed to do that.”

But with a Canadian passport, he’ll be able to leave again.

No treacherous mountain journeys required.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.