Bright lights, big city: How Philly’s new streetlights could make us safer

Philadelphia’s 100,000 streetlamps vary in brightness and intensity, leaving some areas darker, and more dangerous than others.

People stroll past shops as they close for the night at the commercial corridor on the 5500 block of North Fifth Street. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

Terrance Mason has a nickname for 5th Street in Philadelphia’s Olney’s neighborhood: “Saks 5th Avenue.”

The shop-lined street’s steady flow of foot traffic is one factor behind the nickname. The other is the streetlights.

“There are different bulbs here than in the rest of the neighborhood,” said Mason, who has lived in the area for 32 years. “I don’t know why. City favoritism, maybe.”

But 5th Street wasn’t always so bright. For years, the busy thoroughfare and surrounding streets struggled with dim lighting. In 2018, three traffic crashes happened within blocks of one another on West Olney Avenue between 2nd and 5th Streets, all of them at night when subpar lighting left the area dark. The collisions alarmed neighbors and area business owners who had been complaining for years that the dim streetlights made area roads less safe.

“Our lights used to be inadequate,” said Stephanie Michel, director of the North 5th Street Revitalization Project, a nonprofit on the corridor.

Michel and others advocated for better streetlights for two years. It paid off last fall when the city’s Streets Department replaced many of the old lights with brighter lamps.

The city hasn’t yet released 2019 traffic safety data so its too early to know if crashes have become less frequent in on West Olney Avenue since the new lamps went in, but people say they are less scared to walk around at night and driving feels less risky.

“People feel safer walking out,” Michel said. “Businesses can stay open longer.”

Night is the most dangerous time for people who use Philadelphia roads. While the overwhelming majority of the city’s crashes happen during the day, when more drivers, bikers and pedestrians tend to be using the road, crashes at night are four times more likely to be fatal.

Nearly half of all fatal and serious crashes in Philadelphia occur at night, according to city data

That could be because of a multitude of factors: fatigue, impaired driving, glare from headlights or road signs, or compromised night vision.

“A lot of things happen at night,” said Erick Guerra, a professor of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania. “People are more likely to be drunk, people are driving faster because there’s less congestion, people are paying less attention. We get worse driving on a variety of dimensions.”

But while many of these risk factors are difficult to guard against, one significant danger is preventable: inadequate lighting.

Brighter lights, safer streets

Not all streetlights are created equal.

The Institution of Lighting Engineers notes that the lamps used in streetlights vary “in both size and consumption (usually between 35 and 250 watts)” depending on where they are; a residential street, for example, might be illuminated with less brightness than a main road or a highway. In Philadelphia, streetlight wattage can range from 25 all the way up to 400.

But brighter streetlights mean safer streets. Case studies run by the Federal Highway Administration have shown that enhanced street lighting has the potential to significantly reduce late night and early morning crashes. And Vision Zero, a national network dedicated to making streets safer, has touched on the impact of improved street lighting when it comes to pedestrian safety.

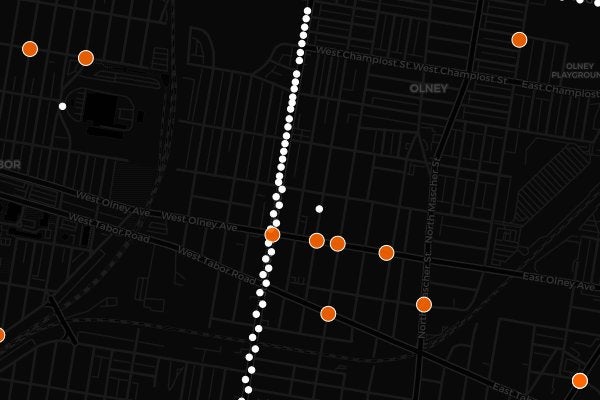

The city’s 100,000 streetlamps vary in brightness. The most powerful of them are concentrated in Center City and along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, as well as along major roads including Walnut and Chestnut streets, Washington Avenue, and Columbus and Roosevelt Boulevards, according to city data.

High wattage bulbs tend to be more sparse, or even nonexistent, in North Philly and the Northeast — places that have also documented a significantly higher concentration of traffic deaths.

The cluster of nighttime crashes along Olney Avenue in 2018 isn’t an outlier. Other dimly lit streets across the city saw higher numbers of collisions at night too.

Crash data from 2018 indicated four nighttime crashes along a singular curve of Lincoln Drive between Henry Avenue and Walnut Lane, an area where only one daytime crash had occurred.

Another cluster of night collisions happened near the intersection of Island and Buist Avenues in Southwest Philly, just past 73rd Street in an area without bright lights, according to a PlanPhilly analysis of city data. In East Germantown, another group of night crashes spanned two blocks between Boyer and Chew Avenues, another area without high-lumen bulbs.

The city’s Streets Department is working to address street lighting concerns, in part with a program that aims to replace Philly’s older yellow sodium lamps with brighter LED ones. Last month, the city and the Philadelphia Energy Authority announced a call for qualifications from contractors interested in the citywide project. The citywide LED-ification is expected to happen within the next two to three years at a cost of $50 million to $80 million.

An action plan for the city’s Vision Zero traffic safety initiative includes lighting upgrades in two projects, a $225,000 project in Chestnut Hill and a $1 million investment in LED streetlights on corridors with high rates of crashes.

“Vision Zero focuses on systemic improvements to Philadelphia’s street infrastructure, including pavement markings, signs, signals, and lighting. Each of these elements plays a role in reducing traffic fatalities,” said Kelley Yemen, the city’s director of complete streets, in a statement.

Yemen said the city is still working on a timeline for the rollout of the new lights, but officials recognize the urgency.

“Upgrading our lighting systems to LED improves visibility especially at intersections and along High Injury Network corridors to help reduce [serious and deadly] nighttime crashes,” she said.

Michel said that N. 5th Street got its new lights partially due to good fortune: Advocates asked for the improvement at the right time.

“They were doing the citywide project of changing out the lights on various corridors, so I would say it was a matter of the city finally being ready and having the funds to do so,” Michel said.

Still, the area remains a work in progress. Some neighborhood streets blaze with a line of bright lights, while other blocks have only one or two.

Back on 5th Street, Terrance Mason hopes everywhere will soon be as bright as his neighborhood’s main street.

“They need to be the same everywhere,” Mason said. “They need to be the same in the whole city.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.