With Boy Scouts opening up, Girl Scouts facing a crossroads

With the Boy Scouts now accepting girls, will the Girl Scouts go the way of all-women's colleges? Or will they take a different trajectory?

Listen 0:00

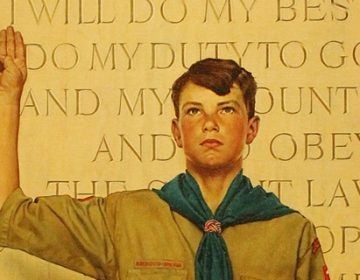

Girls can now chose between the Girls Scouts and Boy Scouts. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Ann Perrone was born to be a Scout.

Her mom was a camp director for the YWCA and family trips tended to revolve around the great outdoors.

“I’ve always been a tomboy,” she said. “[I] like climbing, don’t mind bugs. I love to get dirty and explore stuff.”

When Perrone was a teenager in the late 1960s, she joined a Girl Scout troop in Northwest Philadelphia. She loved the experience and formed lifelong bonds with the other girls in her troop. But as much as they all loved Girl Scouts, it was no secret: they wanted to be out exploring the wilds. What they really wanted was to be Boy Scouts.

“We all wanted to be doing what the boys were doing,” said Perrone.

Years later, when she had a son, Perrone got her wish. For 25 years, she’s volunteered with the Boy Scouts of America, most recently as scoutmaster of Troop 1719 in Germantown. When the Boy Scouts announced Wednesday they’d allow girls to become Cub Scouts and participate in programs that would allow them to earn the prestigious Eagle Scout rank, Perrone was thrilled.

“My own personal feeling is that it’s gonna be a good thing,” she said.

Will Girl Scouts survive?

But what does that good thing mean for the Girl Scouts? If this generation’s Ana Perrones switch their scouting allegiance, could one of America’s great female institutions weaken?

“I think it has a potentially damaging impact on the Girl Scouts,” said Barbara Arneil, chair of the political science department at the University of British Columbia.

Arneil has written about the history of scouting, which in the United States evolved much differently than it has in most countries.

While scouting tends to be coed elsewhere around the world, the Boy and Girl Scouts have developed distinct — and somewhat opposing — identities.

The increasingly countercultural tastes of American youth caused both organizations to hemorrhage membership in the 1970s, Arneil said. Scouting seemed old-fashioned and unresponsive to the changes wrought by the civil rights and women’s rights movements.

But while both organizations suffered initially from their “square” status, they responded to the challenge in different ways.

“The Boy Scouts kind of doubled down,” Arneil said. “After initially kind of toying with maybe embracing the changing norms in society, they actually became more conservative. Whereas the Girl Scouts embraced these various kinds of movements and tried to create an organization that wasn’t as traditional.”

From the 1980s to the early 2000s, Girl Scout membership soared — as a result of the organization’s pivot, Arneil believes. Boy Scouts, meanwhile, continued to lose members.

Lately, though, both organizations have been in an enrollment slide.

Girl Scouts membership peaked in 2003 at 3.8 million, including adult volunteers, according to the Washington Post. Today, the organization has about 2.3 million members. The Boy Scouts, on a similar trajectory, have fallen to about 3.2 million members. Tension between the two organizations spilled out into the public earlier this year when Buzzfeed published a letter from Girl Scouts leadership accusing the Boy Scouts of trying to poach its members.

“They’re trying to figure out how to sustain themselves,” said Kim Fraites-Dow, CEO of Girl Scouts of Eastern Pennsylvania. “And I feel bad for the boys that they’re having to consider not serving boys only anymore.”

All this leaves Arneil torn. She applauds the Boy Scouts’ shift toward greater inclusion, evidenced by this latest move and the organization’s growing acceptance of openly-gay members. But she’s worried about the ripple effects.

“My concern is that this is really about trying to drive up their membership numbers,” she said. “And they’re doing it by kind of pulling folks away from the Girl Scouts.”

Parallels with college coeducation trend

Now it’s tough to tell whether the Boy Scouts’ new policy will actually erode Girls Scouts’ reach and influence.

Perrone believes the Boy Scouts will tend to attract young women who weren’t all that interested in what the Girl Scouts offer anyway.

“Things have a way of shaking out to a new normal,” she said. “I think that’s what’s gonna happen.”

Perrone also thinks the new Boy Scout rules will be a boon for families who want their kids to have access to the same activities.

“I think it’s going to really be a nice package deal for families,” she said.

But if the Girl Scouts do lose membership, it wouldn’t be the first time a venerable, all-female organization weakened when a counterpart went coed. Take the world of higher education.

In 1960, there were roughly 230 women’s colleges, according to the Women’s College Coalition. Over the next two decades, nearly every major university started to accept women. Today, there are fewer than 50 all-women colleges.

Arneil sees some parallels. She worries, for instance, that young women might see the Eagle Scout program — with its deep connections to the nation’s most powerful political networks — as a more desirable rank than anything Girl Scouts can offer.

But she also believes the Girl Scouts start from a far stronger position today than the women’s colleges of the 1960s, partly because of its separate evolution.

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, a professor at all-women’s Smith College who studies women in higher education, agreed.

“There’s such a difference ideologically between the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts that it doesn’t quite work the same way,” she said.

Separate but equal outlook

Those ideological differences could be the key to Girl Scouts maintaining its vibrancy.

“Girl Scouts has been a very progressive organization that has stood firmly in the space of wanting to provide opportunities for girls to lead, even when as a nation we weren’t necessarily there yet,” said Fraites-Dow of Girl Scouts of Eastern Pennsylvania.

At the time they went coed, schools including Harvard and Columbia were widely seen as more similar — albeit more prestigious — versions of their sister schools. That dynamic gave them a clear edge in the competition for students.

“The Boy Scouts don’t have the premier ranking that the strong liberal arts programs at these strong universities did,” said former Girl Scout Patricia Albjerg Graham, who studies the history of American education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Graham, who advised Princeton while it went coed, also went through gender-admission debates at Barnard and Radcliffe colleges.

“I’ve had three rounds of this discussion,” she said.

She does foresee some weaker Girl Scout troops dissolving, just as some weaker all-women’s colleges folded. But, overall, she believes the organization is much better suited to thrive in an environment where its counterpart admits all applicants.

“While I find it amusing that the Boy Scouts have chosen to integrate, so to speak, I hope very much the Girl Scouts will remain for those who wish to be in girls-only activities when they’re young,” she said.

Graham still fondly remembers earning her swimming badge as a Girl Scout in West Lafayette, Indiana. As she recalls it, the rules of the time required her to jump out of a boat with clothes on and find some way to stay afloat and climb back into the vessel.

It was Graham’s father who dropped her in the middle of Lake Superior and supervised her attempts to crawl back into his small rowboat.

“And I got my badge,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.