Black middle class finds refuge in East Germantown’s diversity, gentrifying on their own terms

“I can’t reverse gentrification with one bookstore. But what I can do is model alternatives to what gentrification looks like,” said Hill.

James Earl Davis, a Professor of Urban Education at Temple University and his golden doodle, Baldwin, pictured in his home in East Germantown. (Brad Larrison for WHYY)

Temple University education professor James Earl Davis and his partner moved into their stately 150-year-old Victorian home in East Germantown in 2001, at a time when the neighborhood was, well, iffy.

“The car was broken into around 2002 because there was money and CDs on the front seat. They broke the window and got those, but that was kind of an urban novice error,” Davis recalled with a knowing laugh.

Germantown, which sits in the Northwest section of Philadelphia, is one of the oldest, most historical sections of the city, and architecturally, one of the most diverse. Rowhomes and twins share blocks with Victorians and mansions.

Davis — who’s African American and describes himself as a country boy from Alabama — wanted to buy a single family standalone home, a rare option in Philly.

“We looked in Center City and Fairmount, and we quickly realized if we want more space and acreage, we’d have to move out,” he said. “Someone suggested the Northwest…and we would get more house for the money in Germantown.”

When Davis bought there, he thought he was investing in an area on the verge of major transition — a place on the rebound from decades of disinvestment, political neglect and blight.

But, 17 years later, East Germantown hasn’t changed all that much, at least on paper.

Median household income is $28,000, the same as it was when Davis moved in. In the past two years, 14 people were killed in the neighborhood — about on par with the trend. And the number of owner-occupied units actually dropped, from 41 percent in 2000 to 37 percent in 2010, according to the U.S. Census.

Not that the neighborhood has been static. Davis and his partner have seen a lot in their time there. They watched neighbors come and go. And they endured while their community became flooded with social service organizations, like halfway houses and group homes.

But they’ve seen inklings of positive change.

There has been an uptick lately in the number of college-educated homeowners. And about 10 years ago, Davis celebrated the arrival of a grocery store in a neighborhood he considered a food desert.

The shift pales in comparison to what’s occurred in some of the city’s most gentrifying neighborhoods.

But as potential buyers are priced out of those areas, there’s a renewed focus on East Germantown for homeowners looking to get more bang for their buck — and their presence is gradually transforming the neighborhood.

It’s slow progress, but that’s fine by Davis.

“There’s a fear that if gentrification comes in the way that is hard and fast and furious, it could potentially take some of that community feel, sort of progressiveness from the neighborhood,” he said.

Davis’ block is an eclectic, urban oasis. He lives next door to an African-American fraternity house, Omega Psi Phi. Next to that is a Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall, and down the block, the Philadelphia Tennis Club, one of the nation’s oldest all-black tennis club. Davis says they are all good neighbors.

But go a couple of blocks over and signs of a struggling neighborhood abound. Converted apartments stand next to a long abandoned row house buttressed by a vacant lot.

That’s East Germantown, Davis says.

“You have to be committed to living in this particular context,” Davis said. “I don’t want to say uncertainty, but there’s a different verve in this neighborhood…you make the neighborhood what you want to make it.

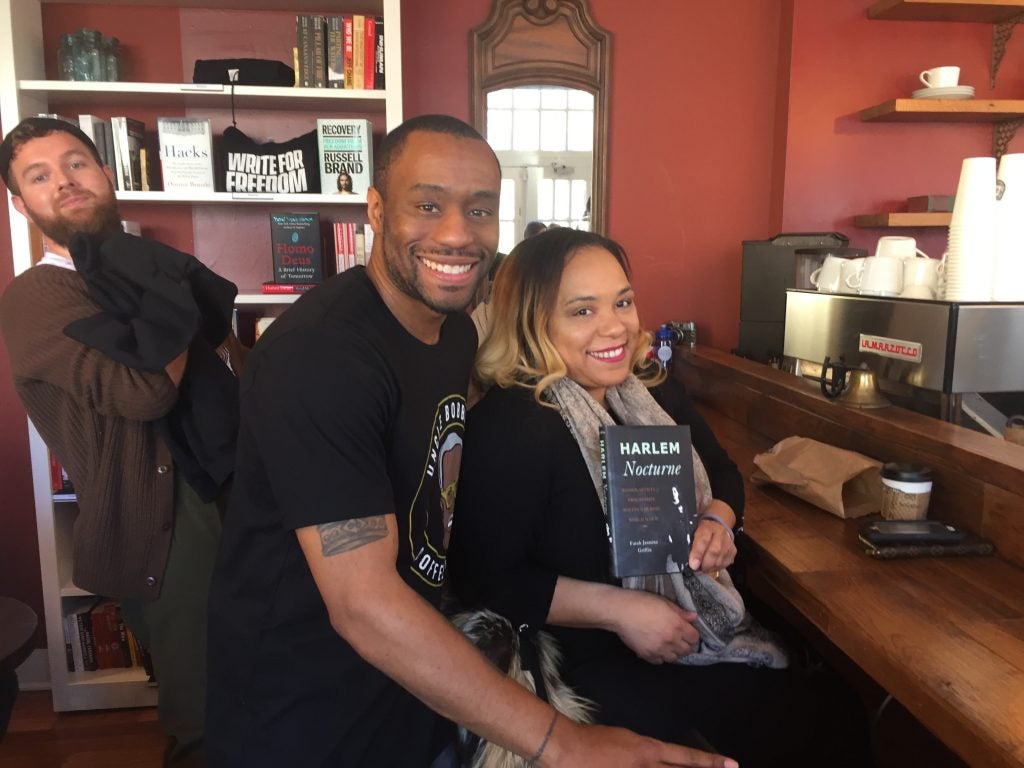

Davis’ neighbor, Marc Lamont Hill, is trying to take that active role. And he’s doing it by flipping a stereotypical notion of gentrification — one of whites opening coffee shops in black neighborhoods — on its head.

He recently celebrated the grand opening of his coffee shop, Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee and Books, on Germantown Ave. It’s a warm, welcoming space, where baristas serve up herbal tea and sweet potato pie. The bookstore features titles by black authors that Hill devoured as a child while visiting his Uncle Bobbie, the shop’s namesake. There’s also a community space next door.

“I can’t reverse gentrification with one bookstore. But what I can do is model alternatives to what gentrification looks like,” said Hill.

Think of it as gentrification for black people by black people.

It’s just what the neighborhood needs, says Nicole Swinson, a black woman who’s lived in the neighborhood a dozen years.

“To get changes, white people have to move in?” she scoffed. “I resent that. Marc is a prime example of how that doesn’t have to happen.”

Hill, who’s a CNN commentator and also a Temple professor, was in his 20’s when he bought his a three-story row home in the neighborhood in 2005.

He was assured by his realtor that within 10 years the neighborhood would be full of “people like you.”

Instead, the recession hit.

“What was interesting after the bubble burst and a lot of people who moved into Germantown who thought they were going to triple their money left. I was left in Germantown with renters, who had already been there,” Hill said

Hill chronicles his experience in Gentrifier, the book he co-authored.

Despite all of the changes, Hill stayed. And not because he’s making some kind of noble sacrifice.

“I like living around black people. I fell in love with the neighborhood, and I wanted to do something to help the people who are here, not the people who are plotting on this place like a colonizer, but the people who are part of this place.”

Davis agrees, and after living here nearly two decades, he’s really embraced East Germantown’s many layers — black and white, richer and poorer.

“There’s always been a diversity in Germantown that people have appreciated — which in some ways can be more challenging in terms of what people want and need from a neighborhood,” he said. “That’s one of the things Germantown grapples with, and that’s what makes it so special.”

—

This series is a collaboration of PlanPhilly, Keystone Crossroads and WHYY News, supported by a grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.