Black Futures Campaign is crowdfunding $100,000 to buy Dox Thrash house

The group behind the campaign wants to buy the Black artist’s house and transform it into a creative hub for North Philadelphia.

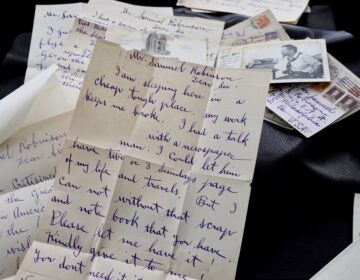

From left to right: architect Chris Mulford, historic preservationist Maya Thomas, and preservation architect Dana Rice are working on a campaign to save the former home of Dox Thrash, a Black artist and printmaker. (Ryan Collerd)

It has never been more urgent to save the Dox Thrash House, says Maya Thomas, who initiated a campaign to preserve the Black artist and printmaker’s former home in Sharswood more than four years ago. Now, she’s hoping to buy the building and make that happen.

The Thrash house, at 2340 Cecil B. Moore Ave., is more or less a shell. The historic rowhouse survived partial demolition with a back end partially torn down, left open to the elements and piled with construction debris. The interior is more or less gutted, with a recent addition of bracing in the form of diagonal beams installed to resolve an unsafe violation of city code. It’s not hard to imagine the damage that more time and exposure would bring.

“It was my instinct to save this house because I’d seen it before in Los Angeles,” said Thomas, who moved to Philadelphia to study historic preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. “I’d seen what happened to South L.A. after the riots and the disinvestment of a community, and then all of that history gets laid over and built over … I saw the same thing starting to happen here, and I got attached to it.”

Thomas and her colleagues, Dana Rice and Chris Mulford, bill themselves as Dox Thrash House Project. Rice describes the entity as an “informal preservation group” that has tasked itself with the dual goal of keeping the house standing and seeing that it is eventually put back in service to the Sharswood community.

Thomas wants to see the Dox Thrash House reclaim its position as an anchor, reestablishing “a community-centered hub of arts.” Preserving the house in a manner that taps into this legacy, Thomas said, will help “establish and bring stability to longtime residents who remember what it is, what it used to be.”

Last week, the group launched the Black Futures Campaign, which seeks to raise $100,000 to purchase the house from the developer who owns it.

In Thomas’s mind, the Thrash House has the potential to set a precedent for how to creatively preserve Black history precisely because it involves taking a house that’s not in great condition — a result of all the compounding effects of systemic racism, she pointed out — and turning it into a model for how historic places might be able to serve their communities.

Though the conditions are certainly not ideal, they’re demonstrative of the reality that many Black communities face, said Thomas. “These conditions are the same reasons why a lot of different African American sites —contemporary or not — get lost.”

Preserving Black history while serving the community of today

The house is listed on the local historic register — a nomination was submitted in 2013 by the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia. Yet 10 years of vacancy led to a current state nothing short of precarious. Over the last decade, the house accumulated a number of city code violations while unaddressed roof damage caused the near-complete deterioration of its interior.

When Dox Thrash House Project first began looking at options to acquire or preserve the property, it was tied up in a tangled title. The listed owner, Shaykh Muhammad Hassan, who purchased the building from Thrash in 1959, had died in 2002.

Hassan was an activist and minister of the National Muslim Improvement Association of America, a well known and respected part of the community in his own right. He hadn’t left the house to any of his children, and while some descendants expressed interest in the possibility of regaining ownership and shared enthusiasm for the group’s vision for its future, resolving the title created a financial burden. Between the cost of clearing the title and the mounting expenses for property damage and resulting legal citations, the project became too costly for the family. In 2019, the property sold at sheriff’s sale for $86,000 to JAS Group Associates, an LLC based out of New York.

According to Rice, JAS Group wasn’t aware that the property was historically designated, or that it had racked up so many violations, including an imminently dangerous violation issued April 2, 2019. Rice said that the company has since applied for an alteration permit to stabilize the property, after the city’s Department of Licenses & Inspections required that it clear the violation before attempting to sell it. That stabilization was completed in fall 2019 and yielded the conditions seen today, Rice said. Within months of the work being done, L&I had issued a new unsafe structure violation, in November 2019.

The property is currently listed for sale for $125,000. Thomas and Rice hope that following their fundraising campaign, they can present an offer to JAS Group to take the burden off its hands.

Alongside the fundraising campaign, Dox Thrash House Project is pursuing fiscal sponsorship through a larger organization to oversee the house. When talking about the house’s future, Thomas cited examples such as the Nina Simone House and the Stony Island Arts Bank by the Rebuild Foundation.

Honoring Black history that was ‘erased’

A renowned printmaker and artist, Dox Thrash was born in Griffin, Georgia, in 1893. He attended the Art Institute of Chicago and was eventually drawn to Philadelphia by the energized community of Black artists and intellectuals that had been developing there.

His home and his studio across the street, which was demolished in 2012, stood right in the heart of Sharswood and in the mix of legendary spots such as the Point Jazz Club, the Checker Club and the Pearl Theater, where jazz greats like John Coltrane and Duke Ellington performed. And they were a short distance from the Pyramid Club, a preeminent social club for Black professionals and an exhibition space where Thrash showed his work.

The area’s history is rich, though little of its physical evidence remains. Around World War II, as more African Americans moved north during the Great Migration, the area around Columbia and Ridge Avenues matured into a hub for Black artists, intellectuals, and activists influenced by the Harlem Renaissance and New Negro movement.

A powerful Black activist presence carried on through the civil rights movement. An impressive list of activists — including Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Cecil B Moore, and Leon Sullivan — had ties to the area, marching, speaking and organizing for civil rights, nationally and locally, including pushing for the desegregation of the nearby Girard College.

But after the 1964 riots along Columbia Avenue, the neighborhood was characterized as dangerous and violence-prone, rhetoric reinforced by the media and the Philadelphia Police Department. Simultaneously, government subsidies encouraged white flight, while racist lending practices devalued property in predominantly Black neighborhoods through redlining. By 1948, the Philadelphia Housing Authority had officially categorized the neighborhood “blighted.”

After decades of struggle, the PHA’s Sharswood Blumberg Choice Neighborhoods Transformation Plan, underway by 2016, included imploding the massive Norman Blumberg Apartment complexes and condemning hundreds of commercial and residential properties, dozens of which were occupied. Some saw the effort as an attempt to further sever the community from its history.

“The whole redevelopment project in itself was a way of erasing the history from that community … without acknowledging how the community came to be the way it was,” said Rasheedah Phillips, an activist, artist, and housing attorney in Philadelphia who started the Black Quantum Futurism Collective (BQF).

Phillips, who also lives in North Philadelphia, set out to document neighbors’ experiences during the tumultuous year that the Blumberg towers came down.

In 2016, BQF received funding to open Community Futures Lab, “a collaborative art and ethnographic research project” that documented and explored the impact of redevelopment and displacement in North Philadelphia “through the themes of oral histories, memories, alternative temporalities, and futures.”

The project operated out of a space at 2204 Ridge Ave. that became a hybrid gallery, resource center, workshop venue, recording studio, and communal gathering spot, where members of the community could gather to discuss the neighborhood’s past, present and future.

“We wanted to support the community and amplify their voices and push back against the narrative that was being shared in the media,” Phillips said. They gathered “oral histories” and “oral futures” to document all of the “beautiful and positive things that had come out of the community,” legacies of artists and activists that had impacted the neighborhood, some of whom, Phillips noted, still live there.

BQF also lent the Futures space to Dox Thrash House Project, so it could present a series of community workshops sharing information about the history of the house and the group’s vision for the future, opening up a dialogue with the community and providing a chance for people to offer input.

Phillips said she sees a place for Thrash’s legacy in the present. “The issues that Dox Thrash was dealing with in the ’40s and pre-civil rights, those same exact issues we’re still dealing with today,” she said.

During the weeks of Dox Thrash House Project’s funding campaign, BQF is donating 100% of proceeds from its book, Space-Time Collapse Vol II: Community Futurisms, to the fund to save the Thrash House.

“I do feel that the physical building is extremely important,” said Phillips. “Overwhelmingly and resoundingly, the buildings that hold meaning and connection to our cultural legacy — we’re seeing them disappear … It speaks to the erasure that we see happening not just of our communities, but of our cultural memories.”

Heritage ‘hanging on by a thread’

Despite the challenges they face, Thomas remains optimistic about the Dox Thrash House’s future. Ultimately, the goal is to turn the property over to an organization that’s already doing work in the community, and the group has identified a handful of potential contenders.

She pointed out a number of community resources that exist nearby — the North Philly Peace Park, Malcolm X House, Cecil B. Moore Library, the Stephen Klein Wellness Center, and the Martin Luther King Center — that comprise a strong network of support and might serve as potential partners.

“I think the best-case scenario is when we’re not needed anymore,” said Rice. “I think we would like for one of the great organizations already out there doing the work, and that appreciates the work of Dox Thrash [to take over the building] … that would be the best long term.”

Until then, they just hope to keep the building standing. Rice and Mulford are both registered architects, and they have the skills and discerning judgment to be realistic about likely future outcomes. They’re also committed to providing some of the preliminary assessments and drawings pro bono.

“This is really one of the last remaining remnants of this heritage in this neighborhood, and it’s hanging by a thread,” Rice said. “An effort like this should have been made 10 years ago, and it probably could have been salvaged to a higher degree.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.