Princeton exhibit focuses on the Mali women who resisted the jihadists

Photograph by Katie Orlinsky

Today, women in Mali can dance in the streets. Girls can spend their days studying in school and their afternoons playing basketball. They can be seen wearing colorful hijab, or shorts and T-shirts; praying or watching TV. They attend wedding ceremonies dressed in their finest, and have their palms painted with henna. Hair-braiding and laundry are part of the daily routine.

Today, women in Mali can dance in the streets. Girls can spend their days studying in school and their afternoons playing basketball. They can be seen wearing colorful hijab, or shorts and T-shirts; praying or watching TV. They attend wedding ceremonies dressed in their finest, and have their palms painted with henna. Hair-braiding and laundry are part of the daily routine.

A woman riding a motorcycle alongside the Niger River in Bamako, her hair flowing in the breeze: The unbridled spirit of these women can be seen in the photographs of Katie Orlinsky, on view at Princeton University’s Bernstein Gallery through January 26, 2017, in A Quiet Defiance: Women Resisting Jihad in Mali. This exploration of women’s lives in central Mali shows how the women resisted jihadist efforts to impose despotic law in 2012 and captures their resilience, dignity and beauty.

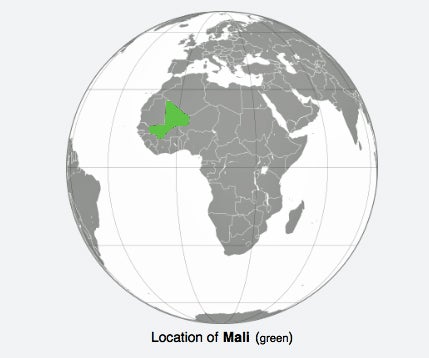

The Republic of Mali, in Western Africa, is that continent’s third largest producer of gold, and yet half the population lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 (U.S.) a day. Mathematics, astronomy, literature and art once flourished in Mali. Most of the nation fell under French colonial rule at the end of the 19th century, then became the Independent Republic of Mali in 1960. Following the March Revolution in 1991, Mali became a democratic multi-party state.

Mali was again threatened in 2012 when jihadist militants took over cities. “Imposing their own despotic version of religious Islamic law, with brutal punishments and public executions, the jihadists threatened to decimate the relics of Mali’s ancient past and suppress the lively spirit of its joyous communities,” says Orlinsky. “In places like Timbuktu women bore the brunt of this crackdown: they were forced to cover their brightly lit clothes with dark hijabs and face-covering burkas, and were banned from work, school, or regular access to medical care. Behavior deemed ‘immoral’ resulted in imprisonment and beatings.”

When an international coalition led by French paratroopers pushed out the jihadists in 2013, a fragile peace ensued. That is when Orlinsky traveled to Bamako (the capital) and Timbuktu (500 miles away on the edge of the Sahara) to meet the women of Mali and absorb their stories.

To survive, many women had fled or hidden in their homes for months, but many also found ingenious ways to stand up to the Islamists’ demands and keep the spirit of their country alive.

Civil unrest and jihadist militias still plague Northern Mali with suicide bombings, kidnappings and a growing conservative Islamic movement. Malian women’s lives, and by extension the identity of Mali, remain at threat. “Their story is not over,” says Orlinsky, a photographer who has worked for The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal and others. She recently won the Paris Match female photojournalist of the year award.

Travel to Timbuktu was challenging. “It was too dangerous to make the journey by road, and the city was completely isolated from commercial aircraft. Eventually I gained access to a plane of special UN forces to get there—and the city was far from post-conflict.” There had just been a failed explosion at the local Malian forces headquarters.

A native New Yorker as well as New York resident, Orlinsky’s interest in international politics and her desire to raise awareness on social issues led her to a stint in Mexico, working as a photojournalist for small newspapers and wire services.

“I naturally gravitated toward covering conflict and social issues, hoping to capture the intimate moments of daily life behind the chaos,” she says. “I was, and am still, inspired by the endurance, dignity and will to survive of human beings despite their difficult circumstances.”

The daughter of theater producers has pursued stories and projects all over the world. “I try to create images that can foster empathy, so that even someone who has no connection to the story or place can see the work and relate to it in some way,” she says. “I like to have the time to just let a story unfold and follow my instinct, allowing the relationships I create to influence and change a story as I go.”

Her focus is on the daily lives of women in situations of conflict and violence, whether in Mexico, Nepal or Mali. “Intimacy is the most important element to making a story work, and it takes time,” says Orlinsky. “As photographers working in conflict zones we generally only have a limited amount time, due to a variety of factors like resources and safety. So for me, one of the best ways to gain access and trust is to have a reciprocal relationship with the people you are photographing. In the case of the images I made in Mali, specifically the portraits, these were women who wanted to share their stories. Some had spent years in hiding, or silenced, and it was cathartic and meaningful for them to talk about what had happened.”

For other women, the trauma was too fresh, and they didn’t want to relive it by talking about it. Others wanted to talk anonymously, but didn’t want their picture taken. Orlinsky made some images of women with their identity concealed by shadows, but in the end decided that wasn’t the story she wanted to tell. “I was struck by the bravery, pride and resistance of the women in Mali, and wanted to focus on that. I only made portraits of women who were eager to publicly share their stories.”

__________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.