An unauthorized Banksy retrospective opens in Germantown

“BanksyLand” has about 50 original pieces by the secretive and controversial street artist. Banksy has neither endorsed nor condemned the show.

Banksy's rats appeared on street signs in Bristol, England, in the 1990s. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

An unauthorized retrospective of the work by Banksy opened in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood on Friday.

The four-day pop-up exhibition, “BanksyLand,” features more than 50 works by the famously secretive British street artist and provocateur whose identity is not publicly known. They include the artist’s early work tagging street signs in Bristol with rat stencils, and whimsical protest imagery merging humor with anti-fascism.

It will be on view through Labor Day.

BanksyLand is an unauthorized traveling exhibition put on by One Thousand Ways, a Portland, Oregon-based company with no direct ties to the artist. Spokesperson Britt Reyes said the company founders have made Banksy aware of the exhibition through his legal representation.

While the artist has not endorsed the show, Reyes said Banksy has not indicated any opposition to it.

“We want his work to be accessible. During the last decade we’ve seen his work be extremely privatized and commoditized, and that’s not his purpose,” she said. “Our goal and intention was to support his reasons and really make this work accessible.”

Philadelphia is the sixth of 11 cities One Thousand Ways is touring BanksyLand. The show is presenting in an obscure location in Germantown: a warehouse space at 219 West Rittenhouse Street normally used by the film production company Rittenhouse Filmworks.

Part of the walls are left as raw brick to give an aesthetically suitable home for the rat street signs, cardboard protest signs, and life-size images of a police officer in full riot gear with a cartoon smiley face, and two male London police officers embraced in a kiss.

The brick wall traces the evolution of Banksy. There are not many details known about his identity or his biography, but it is known that he started as a stencil tagger in the 1990s.

“That’s when we see Banksy introduce himself on the streets of Bristol, tagging up street signs, electrical boxes, government signs,” said Reyes. “Often he introduced himself with a rat stencil, the work being inspired by the early 1970’s Blek le Rat, a French stencil artist, the godfather of stencil art, who also used rats in his work.”

The work on the brick wall shows Banksy using his stencil work in more radical ways, including obscuring a Nazi swastika that had been painted on a wall in Paris, with a pink floral pattern that appears to be painted by the figure of a Black girl.

The original is still on the Paris wall, so this exhibition re-creates the image with high-resolution, life-size photography. It’s one of a few pieces in the show that are recreations of Banksy’s work.

Another part of the building has been built into a white-walled space hung with original screenprints on canvas of works intended for galleries: a triptych of a masked figure throwing what appears to be a molotov cocktail but is actually a bouquet of flowers; a military helicopter flying in combat formation tied with a giant pink bow.

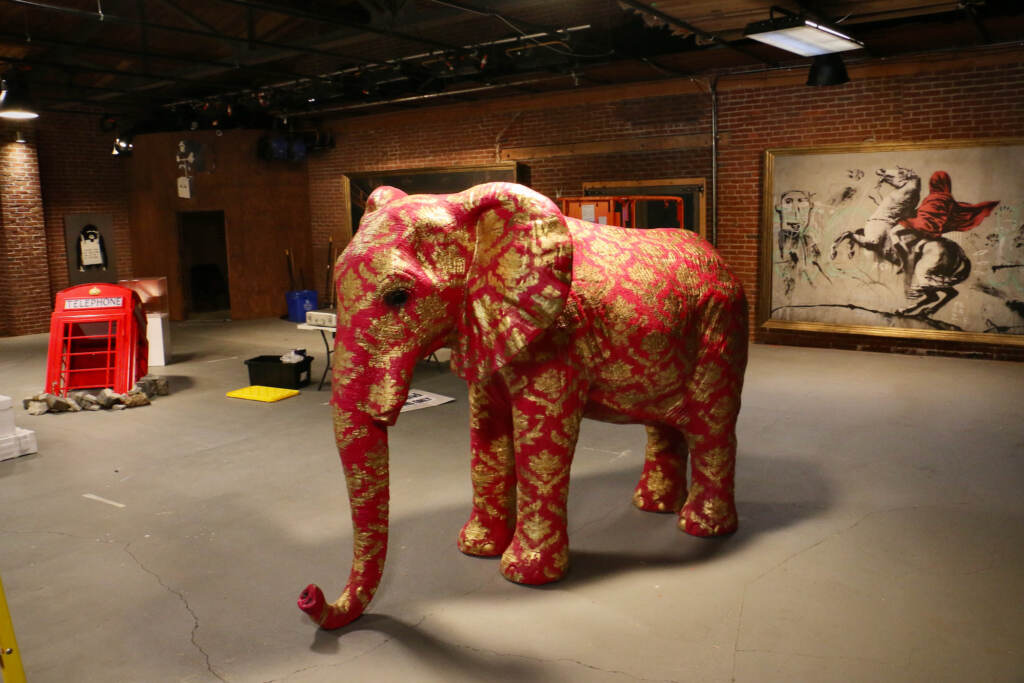

Banksy has become a provocateur in the art world for staging controversial work. In 2006 in Los Angeles, he put a live elephant inside a wallpapered room, and painted the animal from trunk-to-tail in the same pattern as the walls.

It was meant to evoke poverty as the “elephant in the room” that no one likes to talk about, but animal welfare officials condemned the stunt as abusive behavior. A sculptural recreation of that elephant is in BanksyLand.

Later, in 2018, a Banksy screen print of a girl with a balloon was auctioned at Sotheby’s for $1.4 million, but as soon as the gavel went down the print was automatically fed into a shredding machine that was secretly installed inside the frame.

The spectacle that horrified auction watchers was meant to be a comment on the runaway monetization of art. That backfired three years later when the half-shredded print went back to Sotheby’s to be auctioned off for almost twenty times the original price, $25.4 million. BanksyLand features an unshredded version of that girl with a balloon.

Most recently, buildings that have Banksy works on them are fetching higher real estate prices. This week a building in Los Angeles with a Banksy tag went on the market. Its real estate value — minus the Banksy mural — was assessed at $16 million but the art-savvy owners are asking for $30 million.

BanksyLand features photographic documentation of some of Banksy’s high-profile projects, such as DismalLand, a 2015 pessimistic spoof on Disneyland wherein 58 artists were brought in to create a dingy, post-apocalyptic theme park. Some original artifacts, such as a green fluorescent staff safety vest printed with the word “DISMAL,” are included in the exhibition.

Seemingly out of step with Banksy’s ethos, One Thousand Ways is selling its own BanksyLand branded merchandise at the exhibition. The company intends to give a portion of its proceeds to local non-profits in each city it visits. Reyes says the recipients in Philadelphia have not yet been determined.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.