Atlantic slave trade legacy still drives local roots of Black church

As the 400th anniversary of the Transatlantic Slave Trade approaches, religious leaders said the legacy of the early Black church must continue for complete freedom

The Very Rev. Canon Martini Shaw stands outside of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. (Ronald Gray/The Philadelphia Tribune)

This story originally appeared on The Philadelphia Tribune.

Throughout four centuries of slavery and beyond, the Black church has taken on countless forms: a secret meeting place, an intense spiritual gathering, a road to freedom, a ground for rebellion, a refuge for the enslaved, a respite from oppression.

As the 400th anniversary of the Transatlantic Slave Trade approaches, religious leaders said the legacy of the early Black church must continue for complete freedom to be realized among Black people and other marginalized groups — as the ancestor’s way of struggling was most effective.

“I always make a distinction between the versions of the faith that Black people eventually innovated and the version that their captors practiced,” said the Rev. Leslie D. Callahan, who holds a doctorate degree in religion with a focus on African-American Christianity.

“The church was involved in the slave trade and not just one kind of church — the Catholic church, the Protestant church — because the slave trade was a central enterprise,” she said.

“[But] Black people made for themselves a different kind of church and when the Black church is at its best, it continues to embody a warmth and an openness to whomever shows up,” Callahan added. “That’s rooted in the reality that Black people innovated.”

Callahan noted a recent trip that she took to historical sites in Ghana showed the “striking contradiction” of the white church’s Christianity. On top of the old dungeons that held captured Africans sat churches where the captors worshipped, an irony that she says is also key to understanding Christianity in the slave community.

“While Black people suffered extraordinary cruelty, their captors worshipped literally, on top of them, with the sounds and the smells. I can’t imagine how they did it,” she said. “[But] when the [enslaved] started doing church, what they grasped about the Gospel, what they grasped about faith, what they grasped about Jesus was a welcome and an embrace that was not limited, that crossed all kinds of boundaries.

“They reversed the very distinction … that allowed their captives to say they were practicing the faith and enslave them at the same time,” she said.

The Atlantic slave trade started with the Portuguese bringing the first captives from Africa to Brazil in 1526 and continued into the 19th centuries, with estimates putting the number shipped across the ocean at more than 12 million over a 400-year span.

In 1619 the first Africans stepped foot on what became the United States. Records show the English colony of Jamestown, in what is now Virginia, took possession of the bounty that English privateers seized from a captured Portuguese slave ship — at least 19 African captives.

Though the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 banned the importing of new slaves into the United States, the practice came to an end in 1865 with the Union Army victory in the Civil War.

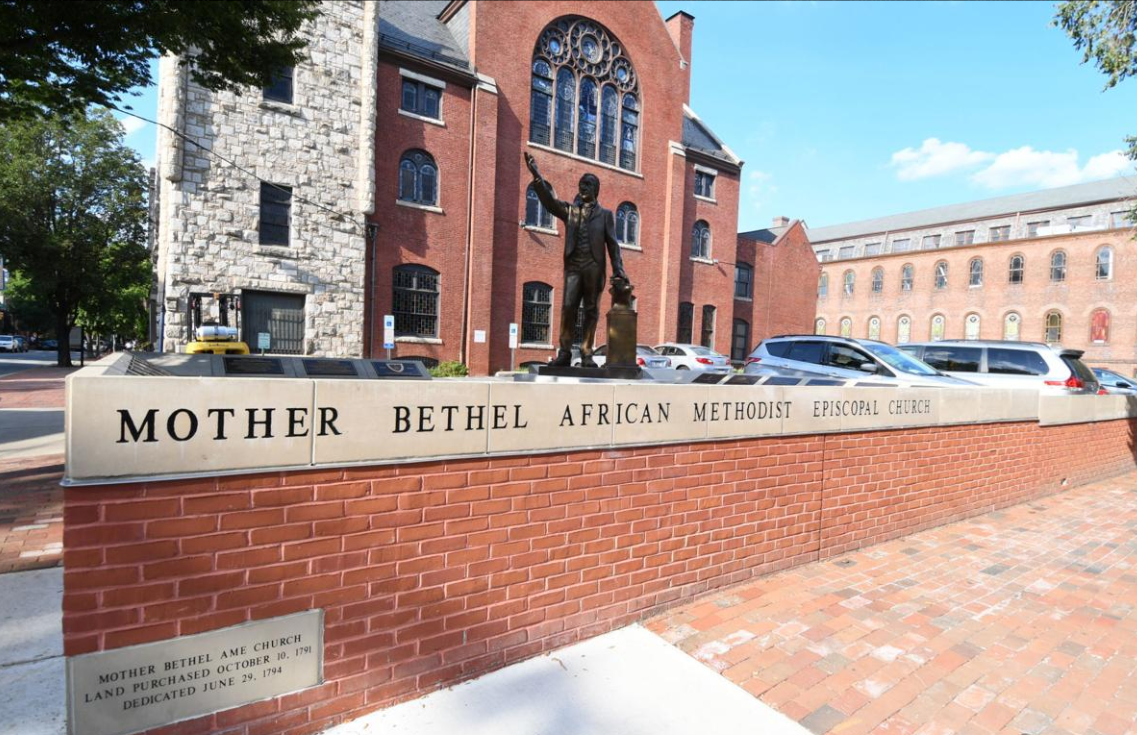

During the intervening decades, the building blocks of the modern-day Black church in the United States was laid in Philadelphia.

The Rev. Mark Tyler, pastor of Mother Bethel AME Church in the Center City area, said as the 400th anniversary of the slave trade approaches, the Black church should reflect on the examples and perseverance of the past and figure out how to show gratitude in active, contemporary ways.

“We need to be grateful in this moment to our ancestors who did not give up in the face of the horror of what American slavery ultimately became. We stand on their shoulders, people who had every right to give up, but who chose to fight for us,” said Tyler.

“We need to show gratitude to them,” he said. “It’s how we live day to day, in a way that reflects people who are grateful for the sacrifice others made for us.”

As the first African Methodist Episcopal church in the nation, Mother Bethel is intimately connected to slavery in America. Its founder, Richard Allen, was a slave who bought his freedom and served as an abolitionist throughout his life. Tyler said Mother Bethel was “probably also apart of the inspiration for Oney Judge and Hercules to run away from George Washington’s white house and free themselves.”

Allen’s wife, Sarah, was referred to “as a friend to the freeing slave” in her obituary, which Tyler says is understood “to be a statement about her activity on the Underground Railroad,” a system of routes and havens for slaves to escape to freedom.

Before Mother Bethel, Allen co-founded the Free African Society as a religious and aid organization with Absalom Jones in 1787 after some unrest worshipping with slave masters and white people in St. George’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.

“Absalom Jones attended church at St. George’s Methodist Church. Blacks in that church had to sit in the balcony,” explained the Very Rev. Canon Martini Shaw of St. Thomas African Episcopal Church.

“Absalom Jones and Richard Allen had been bringing folks in. And the Black population had grown. We know that an incident occurred in which all the Blacks walked out of St. George’s. Two elders led the way, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, and they founded the Free African Society and the first African church came from that.”

The St. Thomas African Episcopal Church was founded by Jones, the first Episcopal priest of African-American descent, in 1792 and is the oldest African Episcopal church in the country. Jones was a former slave who attended church with his slave master. According to St. Thomas’ history, he bought his wife’s freedom in 1770 and his own in 1784.

In addition to Christian gathering, St. Thomas was a platform for Jones’ abolitionist efforts, and was a part of the Underground Railroad.

Both Mother Bethel and and St. Thomas are involved in social justice work today.

Through efforts with Philadelphians Organized to Witness Empower and Rebuild, Tyler and Bethel members have advocated against police brutality, worked with city officials to increase the minimum wage and advocated for equitable funding of the public school system, among other efforts.

Shaw says St. Thomas has a charitable arm and continues to advocate for racial and social justice. He stresses it is important that the church maintains a relationship “with our elected officials,” even the ones with whom it might disagree.

“The moral voice of the church has to be respected by Republicans, Democrats and independents,” he said. “This means crossing the aisle and having conversations with the other [side].”

Despite the past and current work to free and empower Black people, the clergy say there is much more to be done.

Using the example of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave rebellion that killed at least 55 in Virginia, noted by historical accounts as one of the bloodiest and most effective in American history, Callahan observed that moment began as a “gathering of Black folk for worship.” He touts it as a lesson for today’s Black church.

“I’m calling for a resurgence of the Black church as a site for organizing, for liberation and human thriving, but not every church is trying to do that. The creation of our institution is an act of resistance. We need to recover that tradition of resistance,” she said.

“If we start from the moral perspective that everybody who draws breath has a right to things that make thriving possible: housing; water that is drinkable; to be a family with whomever you choose. If we build from that foundation, then you can’t cage children at the border, you can’t cage our children in Philadelphia,” Callahan added.

“America was planted in slavery and fed by slavery and genocide, and we are still bearing contaminated fruit because we haven’t dealt with the roots of our project,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.