At Philly museum, prints charming and Grimm tell story of German Romantic era

-

Festival planners (from left) Danielle Gray of Schuylkill River Development Corp., Katey Metzroth of Secondmuse, Molly Baum of Hacktory and Alex Gilliam of Public Workshop, gather at Grays Ferry Crescent Trail Park to finalize their plans for Discover the Crescent. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Visitors to the Schuylkill River festival, Discover the Crescent, can learn to make their own electric fierflies. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

A coalition of Philadelphia civic groups wants to draw attention to the hidden treasures at Grays Ferry Crescent Trail Park with a weekend festival. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

At Crescent Trail Park, skateboarders take advantage of a small park under the Grays Ferry Road. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Estelle Terrell enjoys a day of fishing on the Schuylkill River at Grays Ferry Crescent. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Most museum exhibitions offer audio guides to help viewers take in the art. In the Honickman and Berman Gallery of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, visitors are instead offered magnifying glasses.

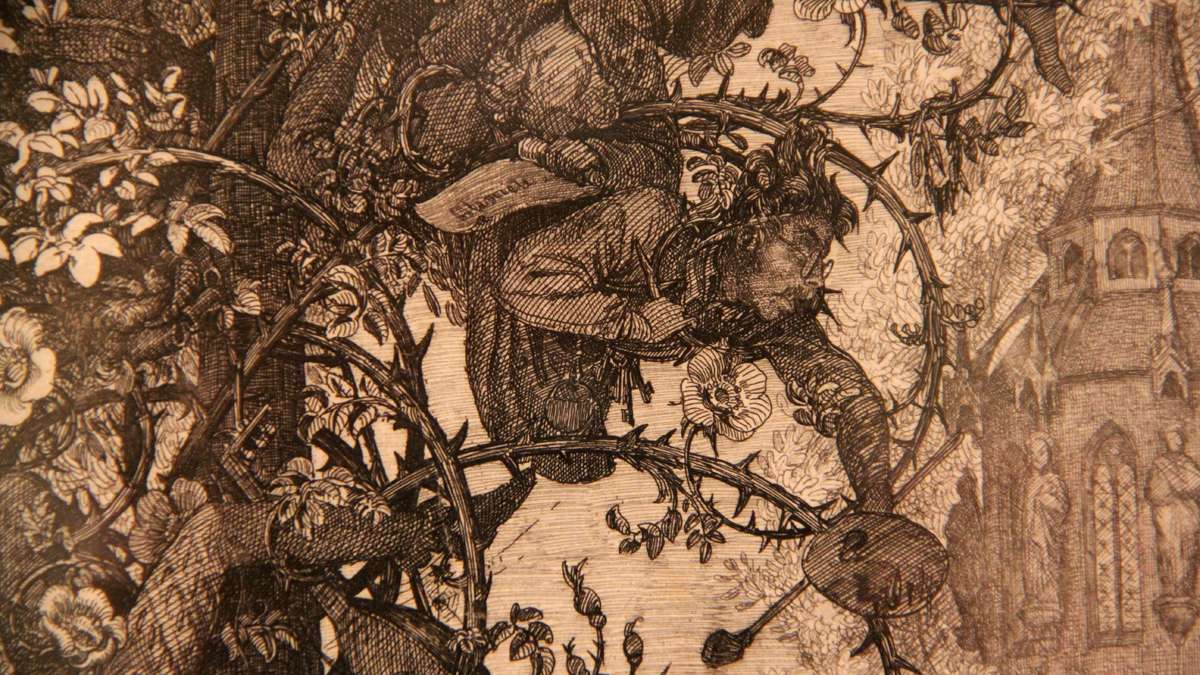

The prints on view, from the German-speaking world of the late 18th to the mid-19th century, are so densely detailed that the plain eye is sometimes not enough.

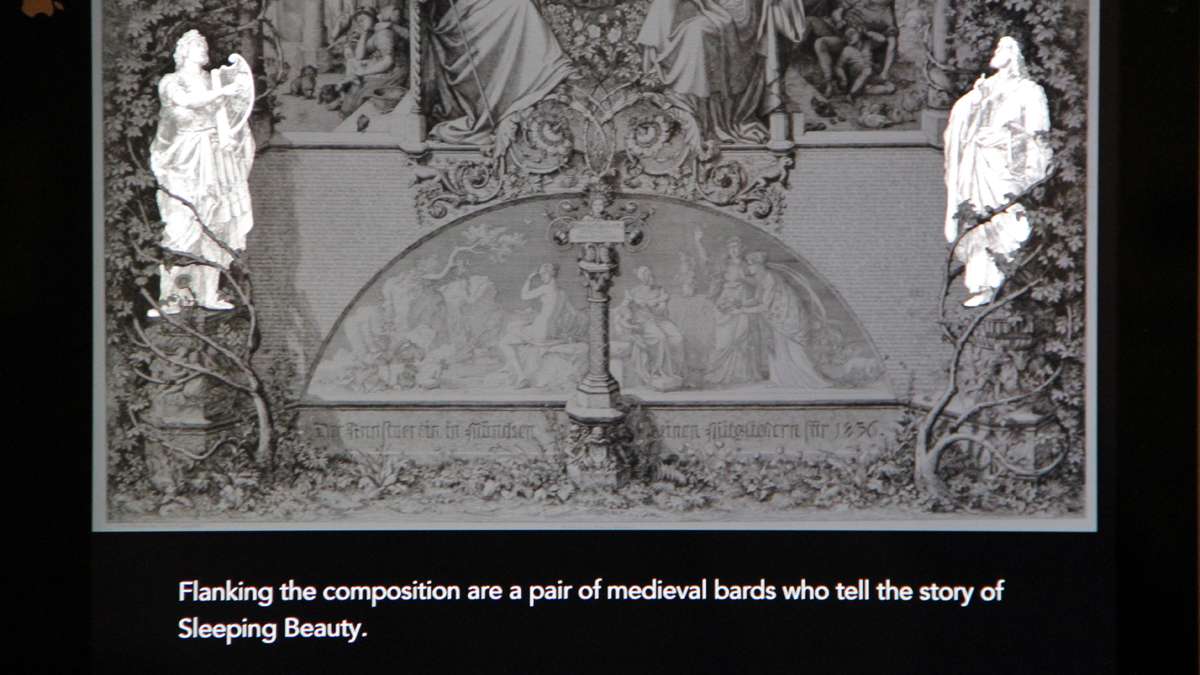

“This particular large print is the story of Sleeping Beauty — also known as Little Briar Rose,” said curator John Ittmann, standing in front of Eugen Napoleon Neureuther’s print from 1836. “It is so densely worked that you can barely make out in the vines that cover the castle. There are these people, young men, caught up in the vines. They are the suitors who tried to get through to win the princess’ hand. They didn’t get there. They got stuck in the vines.”

Hanging right next to Neureuther’s “Little Briar Rose” is a flat-screen computer monitor of the same dimensions, constantly looping through an animated graphic that highlights those doomed young suitors and other obscure details in the print.

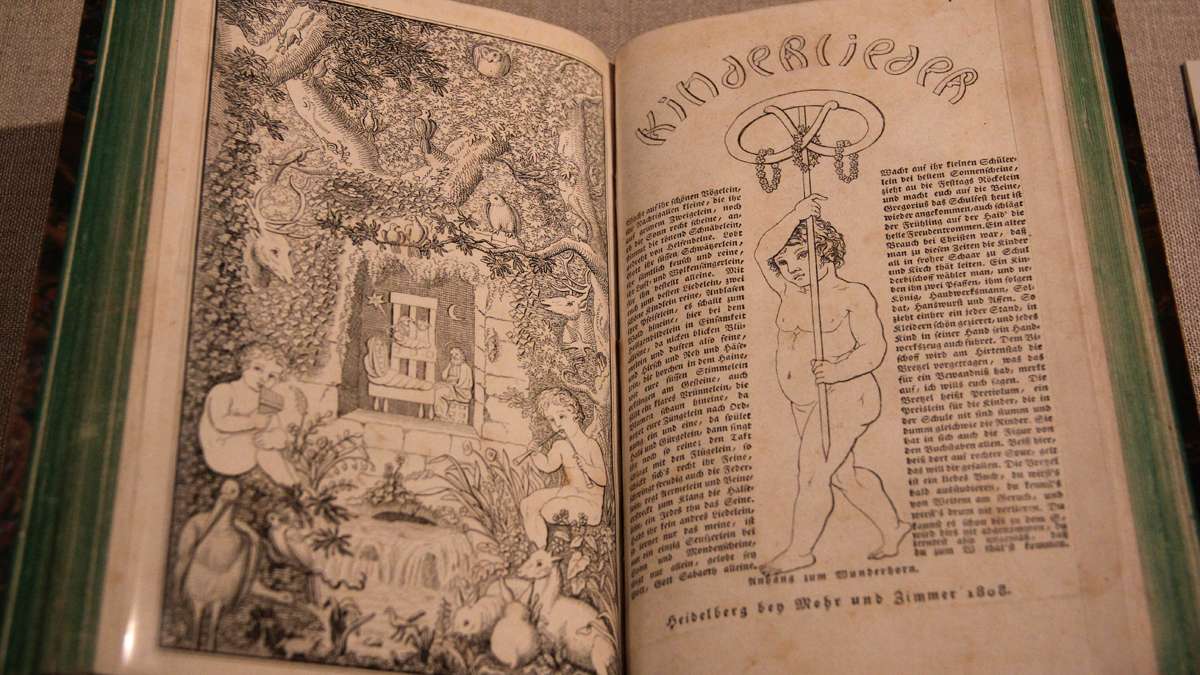

“The Enchanted World of German Romantic Prints,” opening this weekend, features more than 100 prints and a few illustrated books from an era when artists were shifting their focus from biblical stories and formal portraits of royalty to more popular subjects such as natural landscapes, domestic scenes, and fairy tales.

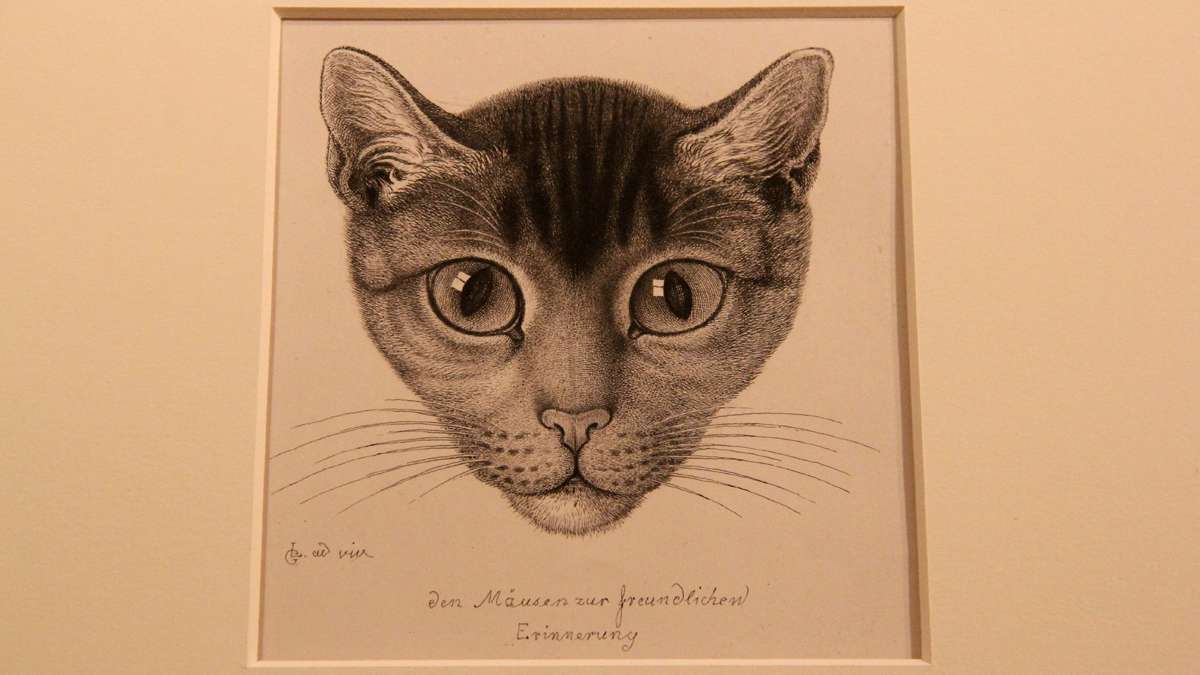

Around that time, the Brothers Grimm were collecting Teutonic folk tales. Ludwig Grimm, an accomplished printmaker, illustrated many of the stories. The Philadelphia show includes many examples of his work, including whimsical images of animals, and a casual portrait of two monks playing with a pet owl.

Printmaking helped make art accessible

“The 18th and 19th century saw an explosion of printmaking,” said Ittmann. “It was no longer kings and princes and fancy folk who collected. It was the prosperous businessman. His family and friends would enjoy them along with him. Friends would come over and look at them.”

This new audience looked at art differently: privately, in the home, up close. That intimate manner of looking allowed artists to get more complicated, more detailed, hiding small details to be discovered by the keenly observant owner.

A bulk of the prints were collected by John S. Phillips in the 19th century, and bequeathed to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1876. When PAFA put the collection up for sale 1985, the Philadelphia Museum of Art snapped it up and spent 25 years slowly adding to it.

The most recent acquisition, bought in 2012, is “A Dance of Death from the Year 1848,” a six-print broadside depicting revolutionary uprisings that had spread across Europe in the mid-19th century. Not long afterward, Germany’s states unified into a nation, the German Empire.

Ittmann says printmaking, and the traditional stories the images tell, helped pave the way to nation-building. “They are able to look back at their own history: ‘We have [Albrecht] Dürer as one of the great printmakers of all time, and we can use printmaking as a way to further German art in a very particular way. It’s sort of our birthright.'”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.