At Penn Museum, a pre-papal ‘flood’ of artifacts looks at links among faiths

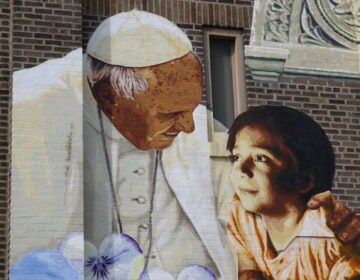

An ancient clay tablet marked with cuneiform, a written language unique to ancient Mesopotamia, on display at Penn Museum (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

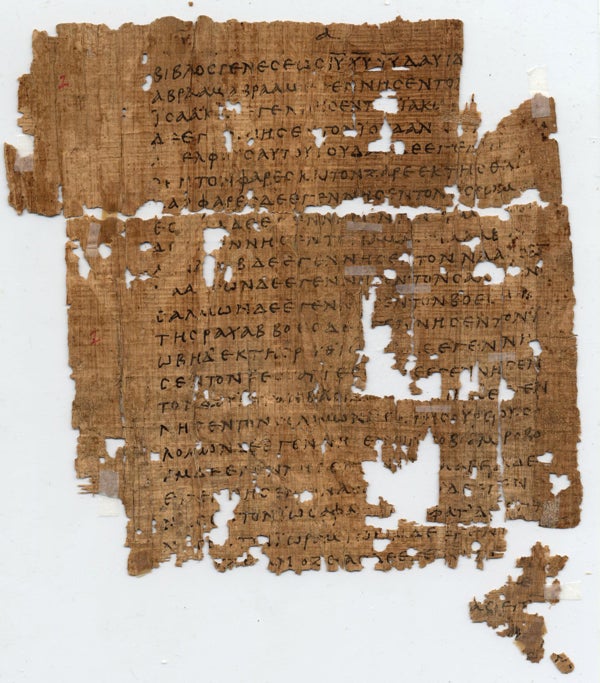

To mark the visit by Pope Francis to Philadelphia next month, the University of Pennsylvania’s museum is exhibiting ancient religious texts from its archaeological collection.

They show connections among Christian, Jewish and Islamic traditions.

The museum found enough space between exhibition halls to squeeze in a quick show of about a dozen text-based objects — two of which are highlights.

One is an ancient clay tablet marked with cuneiform — a written language unique to ancient Mesopotamia. It was likely written 3,500 years ago.

The text describes the story of an epic flood meant to wipe human beings off the planet. It’s very similar to the Biblical story of Noah and the Ark, but the tablet was written thousands of years before the Hebrew Bible.

It’s story describes an array of gods deciding to reboot humanity with a catastrophic flood, but one rogue god decides to warn a single, particularly righteous man to rescue himself and his family with a large boat.

“One of the important differences between the Hebrew Bible and the cuneiform tradition, in cuneiform sin is not an issue,” said Steve Tinney, deputy director of the museum and associate curator of its Babylonian section. “Humanity is too lively, too vibrant, perhaps too immortal. It’s not certain death has been invented at the time of the flood. It may be that humans multiplied so much, they made too much noise for the gods to sleep.”

Tinney has also included a 12th century illuminated Islamic Qur’an, also describing a flood story but more closely aligned with the Biblical version.

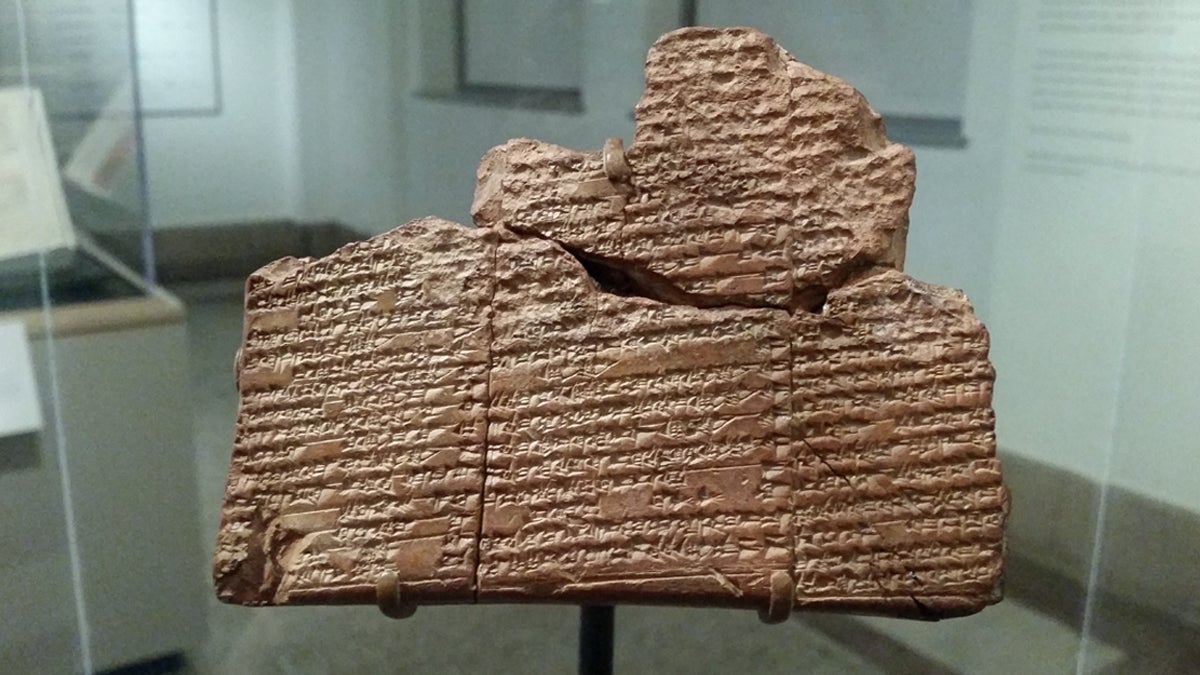

The other important object in the exhibit is one of the oldest written fragments of the Bible, written in the 3rd century.

A fragment of the gospel of St. Matthew. (Photo courtesy of the Penn Museum)

A fragment of the gospel of St. Matthew. (Photo courtesy of the Penn Museum)

It was discovered in 1897 by a pair of British archaeologists digging in a trash mound in Oxyrhynchus, an ancient Egyptian city 100 miles south of of Cairo. Because the Penn Museum helped fund that expedition, it got a portion of its finds.

The expedition found thousands of written documents ranging from the mundane — bills, invoices — to the fabulous. The set of fragments on display, pressed between Mylar, represent the first page of the Gospel of Matthew, written in ancient Greek. At the time, it was the oldest written Bible known.

“It’s the book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ,” said Jennifer Wegner, associate curator of the Egyptian section. “That’s how that gospel begins — giving Jesus’ family tree, if you will.”

Although not seen publicly in over 30 years, the fragment is so often pulled out of storage for scholarly work that Wegner calls it a “frequent flier.”

“Sacred Writings: Extraordinary Texts of the Biblical World” will be on view until Nov. 7.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.