At Gettysburg, many died so the American idea would not

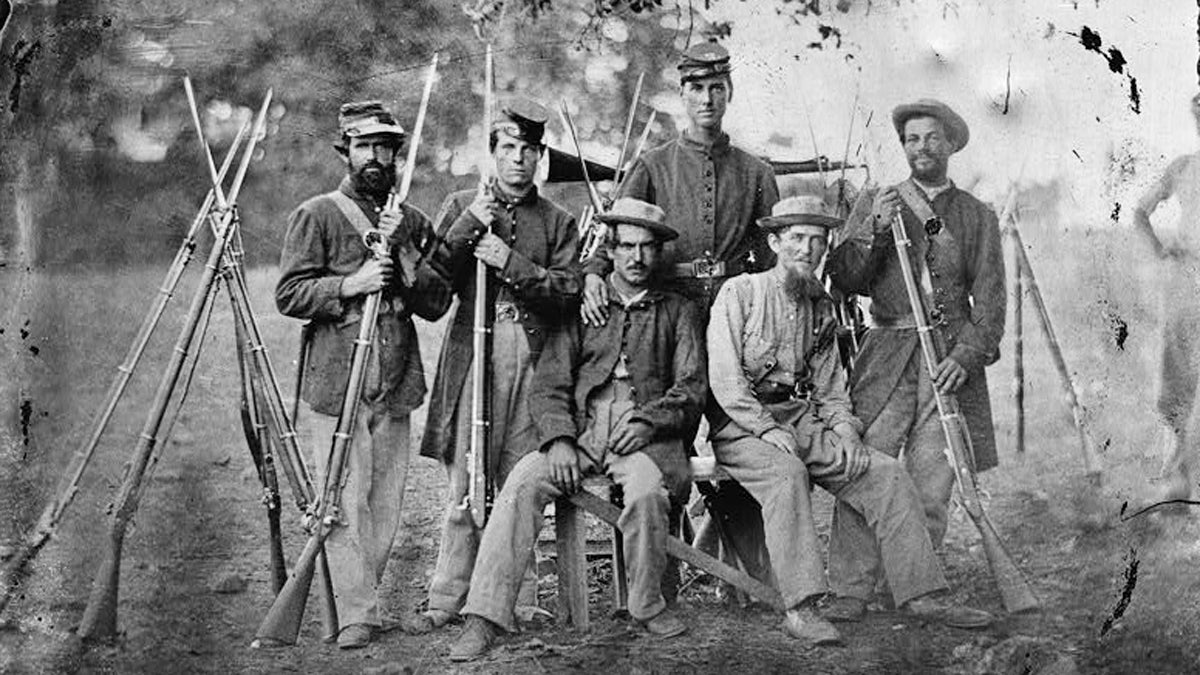

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

What did they die for, these young men in blue? And why should it matter now, 150 years later? It matters, because they died for an idea — the idea of our nation. They fought and died to preserve an idea that we rarely mention anymore: the Union.

Pvt. John Ackerman … Sgt. Moses Baldwin … Pvt. Levi Carpenter …

Awaking on a July morning, they did what young men camped out in a field might do — boiled coffee, stretched, joked, griped about those they were trained to obey.

And in a quiet, inner voice, they prayed to God that this would not be the day.

Pvt. Andrew DeWitt … Pvt. Henry Fenn … Capt. Peter Generous …

For them, though, this day in July 1863 would indeed be the one.

On this day, they would die.

Careening bullets, hot fragments from an exploding shell, or a thrust of tempered steel — one of these things would make their blood leave their mangled bodies, would bid their spirits to depart.

They would be buried far from their home soil, on a shaded hilltop just outside a town called Gettysburg.

In a few months’ time, a long-shanked man in a beard and stovepipe hat would come to that hilltop to praise their measure of devotion.

(And a full 150 years later, plump tourists in Washington Redskins T-shirts would glance dully at their names etched in a semicircle in the orderly grass, and wonder out loud whether it was time for lunch at that tavern on Baltimore Street.)

So what did they die for, these soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, so far from their mothers, their sweethearts, their favorite fishing holes?

Why did they die? And why should it matter now, 150 years later, to us, their distant, self-involved heirs?

It matters, because they died for an idea. The idea of us. The idea of our nation, America, so vast and varied, so rich and contentious, so inspiring and infuriating in the ways it uses the freedom that young men’s blood has bought.

These young men in blue died — some out of commitment, some because they were swept up in history’s fierce tide — to preserve an idea that we rarely mention anymore: the Union.

We speak little of it today, but within their idea of Union lay all that we casually salute at ballgames, picnics and parades.

Within their idea of Union glimmered the hope of freedom for the chained man with welts on his back, for the woman bowed from care and the casual scorn of men.

Their gaunt president would eventually give best voice to this American idea — government of the people, by the people, for the people — in a burst of autumn eloquence on that shady hilltop.

But first, on the fields and hills outside of Gettysburg, that idea would be very nearly lost — and very narrowly saved.

Never closer to collapse

Winners write the histories, which then settle into rote fact and cliché. The truth of a perilous moment can lose its edge. But here is that truth: Over three July days in 1863, Mr. Lincoln’s nation, his dream of imperishable union, teetered near the abyss.

Never was the Union more at risk than on the battle’s second day. In the urgent hours between 4 and dusk, crisis flared from one thunderous, blood-soaked end of the battle line to the other.

The battle’s next day is the one that now soars in legend, when Pickett’s Charge dashed itself against a low stone wall, 10 strides shy of triumph. But it was on July 2, 1863, that pell-mell, last-minute bravery in blue most clearly saved the Union.

At the dire moments, from Little Round Top to Cemetery Ridge to Culp’s Hill, the men of a few blue regiments found it within themselves to race into the smoking maelstrom, instead of away. Among them: The 20th Maine. The 1st Minnesota. The 9th Massachusetts.

If the courage of these bands of brothers had been one ounce less, or come five minutes later, the America we know would have been divided, distorted into something we would not recognize today.

The men in gray were that relentless, that close to their goal.

But, in that noisy dusk, men in blue did the necessary, and often fatal, things to blunt Robert Lee’s last invasion, to snatch Abraham Lincoln’s dream of America back from the precipice.

Late on that second day, the 1st Minnesota was called upon to plug a gap in the Union center. Flags flying, the 262 men of the regiment marched forward. A few minutes later, only 47 of them were left standing.

But their lives bought precious minutes, and America was not lost.

We must never forget

This was no push-button war of drones and precision bombs. It was intimate, hand-to-hand, ugly in the moment and horrific in the aftermath. The wounded moaned in the crumpled fields, beneath the amputated trees. The surgeons’ saws grew dull from use.

It was chaos unleashed upon an otherwise ordinary Pennsylvania landscape — gentle ridges, a peach orchard, a wheat field, a warren of boulders known as Devil’s Den.

In these three days, more Americans died (and let us count the men in gray as Americans, too, for that is what this conflict proved them to be) than in the long anguish of the Iraq War. In three days, 52,000 either died, were wounded, were taken prisoner, or melted into the mist.

Over three days, our nation came as close to collapse as it ever has, and (let us pray) ever will.

Over three days, uncommon courage secured the birthright that we Americans now receive when we draw our first breath, that deposit of opportunity, liberty and faith in the future.

Privates Jacob Mauch, James O’Neill and Danford Parker …

Michigan farm boys, Massachusetts clerks, cocky Irish from Brooklyn. In dying, so horribly and in such droves, they bequeathed us our nation. That is why this battle anniversary matters.

As the long man in the tall hat once said, this is why we must never forget. On these ordinary Pennsylvania hills and fields, the extraordinary idea of who we Americans are, and who we might become, nearly died a bruising death.

Capt. John Hart … Lt. William Jewett … Private Joseph Kleinfelter …

But they, and thousands of others whose names we no longer know, would not let it.

Let us not forget them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.