As always, Barney was very Frank

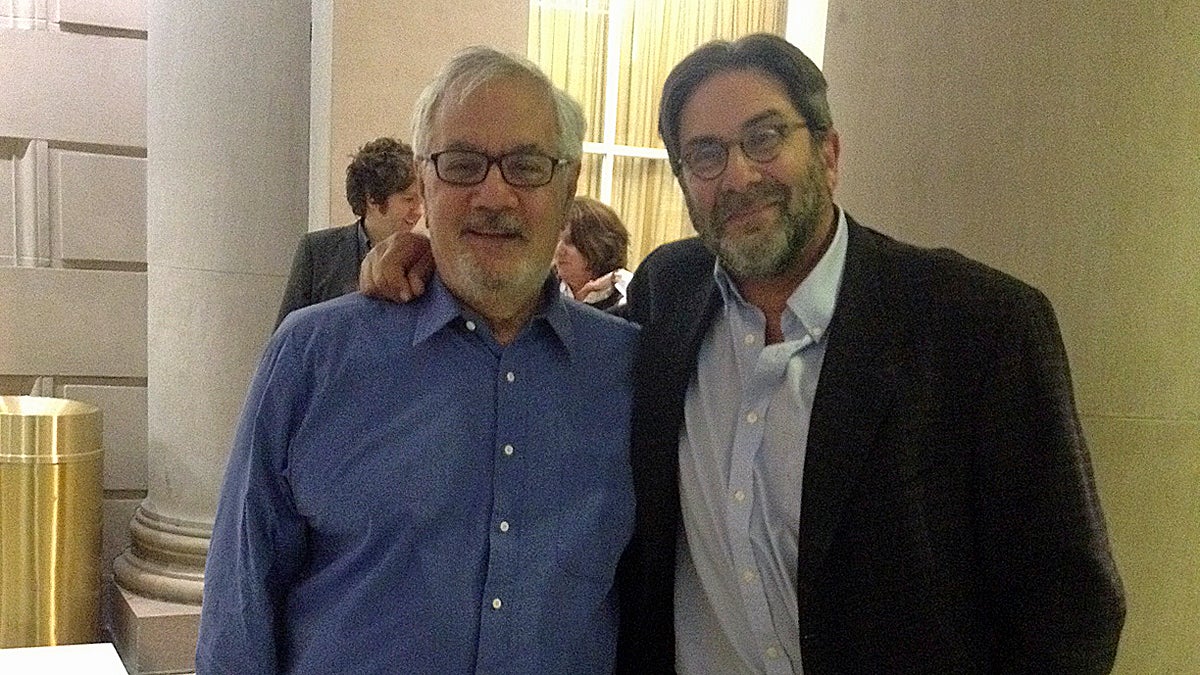

Barney Frank and Dick Polman at the Free Library of Philadelphia (Image courtesy of Polman)

No matter how you feel about Barney Frank (and no doubt you have an opinion), surely we can all agree that he has lived quite a life. His slow journey from the closet to the cultural mainstream was often tortuous, as it has been for many gay Americans of his generation, and until recently he never thought he’d reach the promised land.

He and I talked at length about that journey last night, on stage at the Free Library of Philadelphia. Now retired at age 74, he’s still the puckishly pithy guy who cut a swath during his 32-year House career. He doesn’t appear to have mellowed much since he left the chamber in early ’13, but he’s happily amazed that he’s no longer “an involuntary member of one of America’s most despised groups.”

He was in town to hawk his new memoir, and he naturally speed-rapped about lots of stuff – everything from ISIS to Netanyahu to the usual Republican idiocies – and he still delights in discomfiting his allies. He was particularly scathing about liberals who get too easily disillusioned: “We have leftist voter suppression of an intellectual sort. If you keep telling your people that nothing is any good, nothing good ever happens, that (politicians) only listen to ‘big money,’ then your people aren’t going going to vote….When the right gets mad, they vote. When the left gets mad, they march.”

But Barney the man is arguably most interesting. Imagine what it must have been like, being 14 years old in 1954, and knowing that you’re gay. Imagine launching a career as a public servant in the late ’60s, as an aide to the mayor of Boston, and knowing that your viability on the job hinged on the suppression of your true self. Back then, any gay serving in government knew the score. Barney knew; he had studied it all at Harvard.

He said last night, “(During the ’50s), when the Democrats controlled the Senate, there was a report entitled, ‘The Appointment of Homosexuals and Other Perverts in Government.’ And being ‘out’ didn’t help, because we were seen as morally criminal.” Gays in government – and gays working for private firms with government contracts – were viewed as security risks, courtesy of an executive order signed by President Eisenhower. And as late as the ’80s, “when I first got to Congress, I would get calls from very worried, frightened gay and lesbian people, working for private companies, and who were about to get their lives examined – the idea of the FBI going around and asking questions about you – and they (felt) that they had to quit. It was a very intrusive process. It lasted 41 years.” (It ended at 41 years, because Barney got Bill Clinton to nix Ike’s order.)

It was tough to get phone calls like that during the early ’80s, because Barney was still closeted, still terrified of public repercussions. In his memoir he writes, “The conflict between my crusade against homophobia in the country, and my accommodating it in my own life, was becoming unbearable…I could no longer urge other members to show political courage on our behalf while I opted for cowardice.” Plus, “I was tired of having to desex my pronouns, ration my visits to places I wanted to be, and avoid dancing with another man anywhere I might be photographed.”

I asked him about the constant need to desex one’s pronouns. How did that work?

He replied: “You don’t want to say he – and tell the truth. You don’t want to say she – and lie. My policy had always been that you should never lie, but you don’t always have to volunteer the truth. And if (people) wanted the whole truth, they’d have to get a subpoena. This was going on in my daily life…. You’d have to stop and think, or you’d give yourself away.”

Did all this hiding take a big toll on your psyche?

“Yes. On my personality, on my judgment….I was unhappy in my work. It interfered with my work. You know, legislating is very interpersonal. Particularly, to be an effective legislator, you have to have a great capacity to (diplomatically) reveal the fact that you think somebody (you work with) is stupid…But my capacity to do that was limited because I was so unhappy.

“The best career in the world is no substitute for the kind of emotional and physical needs that most of us have. And beyond that, I found there was a great disparity between a career that was prospering and that was bringing me great credit, and then going home alone at night. There was always that old song, ‘Saturday night is the loneliest night of the week,’ and that just got to me.”

He finally came out in 1987, signaling to the Boston Globe that he’d say yes if asked the question. Fortunately for him, that was the pre-Internet era; in the digital era, politicians have less control. I asked Barney if he was glad that YouTube wasn’t around back in the day.

Obviously, he agreed: “I didn’t want to be seen in certain places – but in an age of everybody having a camera, you’d either have to be totally out or totally closeted. What I tried to be, in the early ’80s, was sort of live half in and half out. Publicly, I was sort of ambiguous; privately, I socialized with the gay people. But I could not have done that in an age of cellphone cameras and the Internet.”

The good news, of course, is that, since the ’80s, Barney and his peeps have moved into the mainstream. I asked, what’s the biggest reason for this seismic cultural shift?

He replied: “It’s the decision by millions of us to be honest about who we are. Our reality has defeated the prejudice. The prejudice was literally ignorant, based on stereotypes. You know – and this is a little bit of an aside – people used to say, ‘Why do you have to talk about being gay so much?’ I’d say, ‘We don’t really talk about our sexuality any more than straight people,’ but the difference is, when straight people discuss their sexuality, it’s called ‘talking.’ When we do it, it’s called ‘coming out.’…And most gay people have straight relatives. And people say, ‘Oh, that’s my teammate, that’s my doctor, oh I know her, she went to school with my sister.’ That’s it – our presence, without hiding….

“The pace has gone faster and faster, culminating with the notion that I could marry the man I love (Jim Ready, in 2012) as a sitting member of Congress. (Not long ago) someone could’ve asked, ‘Don’t you think that by marrying someone, it’ll be controversial?’ Well, actually, it was controversial -a number of my colleagues were angry that I didn’t invite them!”

In the memoir, he sums it up: “Looking back, I think I was pretty good at my job. Now it is time to be good at life.” I asked him about that line. Looking ahead, what’s his definition of a good life?

Response: “Spend time with Jim. Get involved with issues of my choosing on my terms. Not be stressed. Not to do anything I don’t want to do.”

So give it up for Barney. We all love a happy ending.

Follow me on Twitter, @dickpolman1, and on Facebook.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.