Andorra studio aims to capture the feel of a live performance in recordings

At around 11 a.m., a doorbell sounds inside Daoud Shaw’s basement. It’s time to record.

The veteran music producer swings open a green door and welcomes a four-piece band, instruments in tow, into his Andorra home.

As his friends finish setting up, Steve Hastie, Not My Dogg’s lead singer and lead guitarist, sits down with Shaw to talk strategy about a Latin-infused tune.

“Maybe,” one of a handful of tracks on the roots rock outfit’s debut album, has a long, down-tempo introduction. The rest is distinctly faster.

Shaw thinks the band should play the entire track instead of recording the two parts separately and stitching them together in post-production.

“The intro, the legato section, could inspire what’s happening with the up-tempo thing and then some great things could happen,” he says inside Radioactive Productions’ cozy control room.

Hastie nods. He feels the same way.

“As long as there’s ways that you can play with slightly different things with the speed of that second part, I’d prefer to go all the way through,” he tells Shaw.

Shaw’s approach to recording is rooted in trying to capture the essence of a live performance.

Whenever possible, he has clients play in the same room, typically the converted garage space that sits a few steps above his control room, a former family room.

“There’s just a magic that happens even if you have a written arrangement,” said Shaw before the Saturday session gets underway. “There’s something that happens when people react to one another…the whole can be more than the sum of the parts.”

A different era of recording

Shaw, an accomplished drummer, started working with bands in the late 1960s, when songs were captured on tape using analog devices, not digitally.

He doesn’t use tape anymore, but his philosophy towards recording and producing has remained anchored in that era. It’s what he’s most comfortable with and what he thinks best captures the vibe he likes to hear woven into every track.

“I’m old school.” Shaw says with a smile.

That’s not to say he opposes modern recording techniques.

Shaw worked in media production, including for WHYY, for years and uses a mix of analog and digital gear.

He simply leans towards using more pre-production techniques — i.e. microphone placement and coaching — than post-production techniques — i.e. layering tracks and snipping together parts — to get the end product he wants.

Shaw, for instance, makes editing decisions on the fly.

“I’m used to calling stuff as it goes down and I’m probably right 70 percent of the time and that’s good enough,” says Shaw, a former drummer for blues, soul singer Van Morrison. “It saves countless hours and hours and hours in decisions later.”Industry experts agree: Shaw is a bit old school. But they’re not ready to put him on an island or call him a dying breed.

In fact, they say some elements of his approach are ideal.

“Believe or not, if you have a recording studio that has the capability to record everyone in the room at the same time, you really do want to do that,” says Craig White, who runs The Lab in the city’s Callowhill section.

“You can have a computer and one guy sitting in a dark room and programming a song, but the best vibe and the best feeling from a record comes from having interplay between musicians.”

White, who was chief engineer at the famed Philadelphia International Records for years, notes that approach, at least when it comes to instrumentals, is beginning to become popular again.

A number of his customers have asked for as much.

“It’s beginning to come full-circle,” he says.

Jack Klotz, director of Temple University’s recording industry concentration, says there’s “a lot of sympathy around the industry” for Shaw’s approach.

“Music really, at its heart, is an emotional event. It’s this soul-to-soul communication that sort of happens and it happens in this ever-changing instant. And the biggest thrill one of us gets is when we get to capture one of those things.”

‘It’s got feel’

Over the past 40 years, Klotz, who also produces classical and jazz music, says recording music, has become a different craft where producers and engineers go after “more and more perfect sounding records.”Shaw barely advertises. He’s got a website, but says all of his clients come via word-of-mouth.

The strategy has kept the studio in business for two decades.

“It’s like a chain-reaction. My little chain has been enough to sustain a studio and do lots of projects,” says Shaw.

It’s also meant that he hasn’t had to turn away many bands. Groups, like Mt. Airy’s Not My Dogg, usually seek out Shaw because they want to record his way.

“The strength of our sound is how we play together in a live situation and that’s what we want to capture,” says Matt Hagele, the group’s bassist. “People who come to our shows who want a CD, that’s what they want to hear.”

Colin Browne, the band’s percussionist, says Shaw’s philosophy help keeps that sound, that vibe, intact as much as possible.

“When you construct a song, you work on it for months or whatever, typically you come into a studio and you deconstruct it, which can be disconcerting,” says Browne. “This gives us a chance to not tear it apart so much and put it back together like a puzzle.”

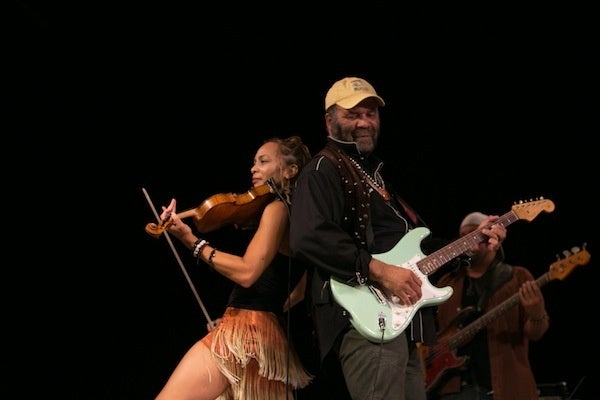

“It’s not overproduced and it’s got feel.”Watch a clip of Daoud Shaw performing on the drums with Van Morrison and the Caledonia Soul Orchestra in 1973.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.