An organization that builds parks is making public art about heat

The Trust for Public Land is working with Philadelphia artists and community leaders in three of the city’s hottest neighborhoods.

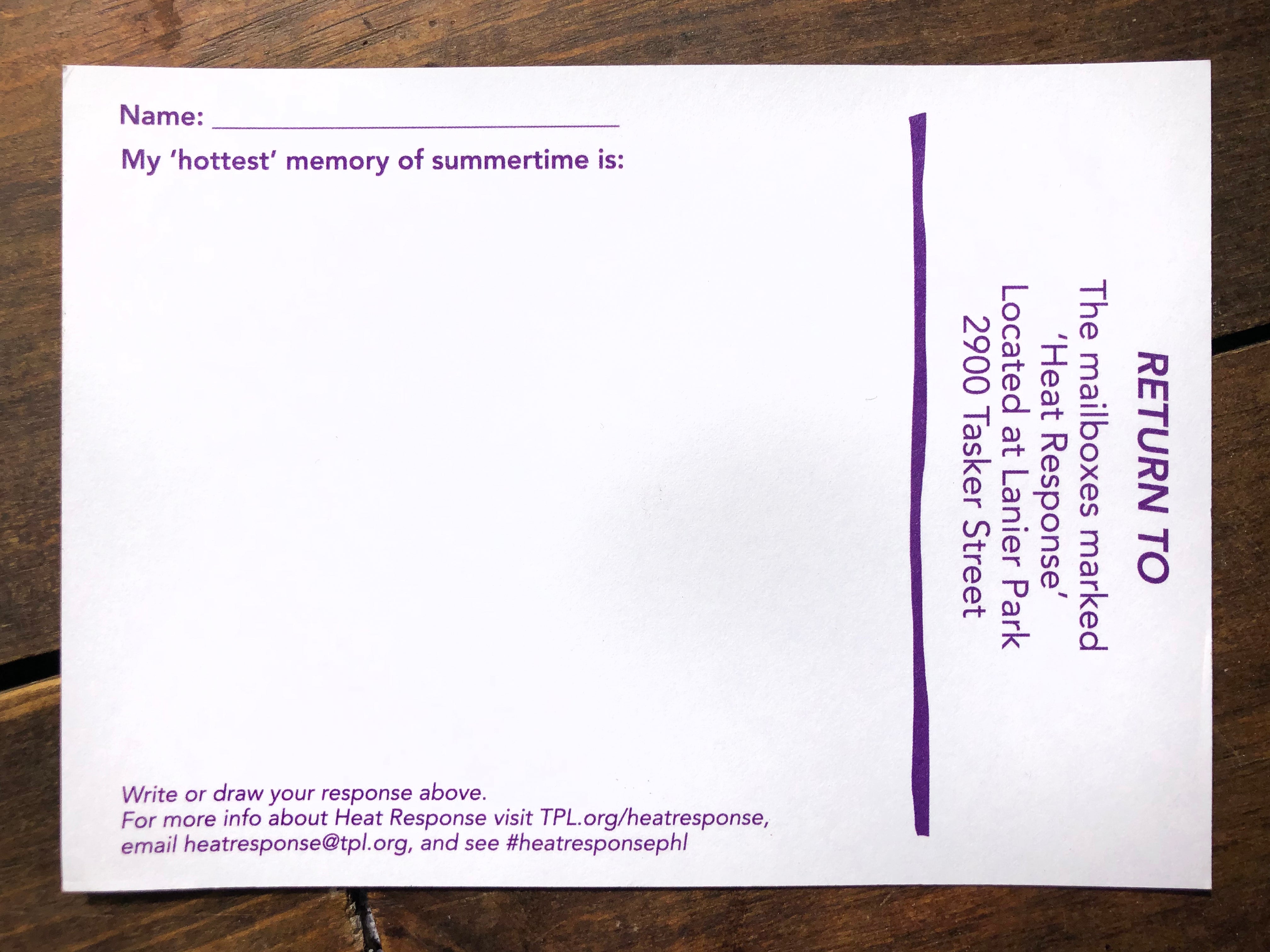

Jenna Robb distributes postcards in Grays Ferry. (Courtesy of Jenna Robb)

A big oppressive sun is the constant in a series of postcards that made the rounds in Grays Ferry this summer.

The postcards, made by artist Jenna Robb, distributed to Grays Ferry neighbors and collected in a special mailbox installed at Lanier Park, are the first sign of a community-based project slated to last two years and change the conversation about rising temperatures in Philadelphia and other cities around the globe.

Robb illustrated the cards with drawings of people experiencing heat in the city — kids playing in front of an open fire hydrant, someone walking under a big umbrella. On the other side: questions for people to answer about their experiences of summers. The goal is for people to share their experiences of living in one of the city’s hottest neighborhoods.

“Folks need to be listened to and heard, and so that’s where I started because those are expressions of how it really feels to live in this neighborhood,” said Robb, a textile designer and art educator who lives nearby.

Her project will also include listening to kids’ experiences through free Saturday art workshops held in Grays Ferry’s Lanier Park over the next two months and other programs. All of it is part of ‘Heat Reponse,’ a Trust for Public Land initiative that aims to use art to build awareness of urban heat, a growing public health threat associated with climate change.

The national nonprofit, best known in Philadelphia for working with public schools to build playgrounds, is focusing the initiative in three of Philly’s hottest neighborhoods: Grays Ferry, Southeast Philadelphia and Fairhill. In these three neighborhoods, community leaders will work with local artists selected by environmental artist Eve Mosher, who is leading the project. In 2014, Mosher, who is based in New York, created a version of her famous piece “HighWaterLine” in Philadelphia marking a chalk line through Port Richmond, Fishtown and Kensington for residents to see the areas that would be flooded out by a 10-foot storm surge.

The number of heat deaths have declined in Philadelphia since the city pioneered a response system in the ‘90s but sweltering temperatures continue to kill more people than all other natural disasters combined. And the threat is growing: climate projections say the number of hot days will double during this decade.

But not all Philadelphians are impacted the same way. Formerly redlined neighborhoods, and today’s poorest areas, are also heat epicenters, where surface temperature can be 20 degrees hotter than in richer and greener districts.

Mosher selected local artists with ties to the communities where they will be working. Linda Fernandez and Keir Johnston from Amber Art and Design, the public art collective selected to co-lead the project in Fairhill, have worked in North Philadelphia for years. Leading the work in the Southeast will be José Ortiz-Pagán, a visual artist who has worked with communities in the area on projects such as the annual Día de los Muertos celebration organized through Fleisher Art Memorial.

The teams will spend the first year listening to people’s stories and learning how they deal with heat every summer. Mosher said Fernandez and Johnston are working with Fairhill leader Charito Morales using poetry and storytelling as a way into the community, while Ortiz-Pagán is working around food. During the second year they will create a work of public art that speaks to how the community wants to respond to extreme heat.

“The experiences the people have with urban heat are oftentimes not used to inform conversations about how urban heat is addressed,” said Owen Franklin, who directs The Trust for Public Land in Pennsylvania. ”We feel that there’s a very rich and important information source going unchecked and going untapped, and so we look to elevate that.”

While The Trust for Public Land has developed several playgrounds and parks in Philadelphia, Franklin said this is the organization’s first project focused on heat. The goal is to learn more about the role that parks can play in addressing climate change.

“They cool the air, provide a safe space to get outside, and help connect people to each other and find support during times of difficulty,” he said. What else parks offer or could offer, project planners hope to explore.

Councilwoman Katherine Gilmore Richardson, who chairs the Council’s environmental committee, said the initiative is a step toward changing a status quo in which a person’s lifespan can be predicted by their zip code.

“In Philadelphia, your zip code determines your life expectancy, and heat is playing a more robust role in that reality,” she said. “Because of the severity of the impacts of heat and the inequities it causes in our city, this issue rises to the top for me.”

Creating solutions on the ground

In Fairhill, Charito Morales already knows her community needs a lot of resources to combat extreme heat, starting with more green spaces and cooling centers.

“When it’s hot in the summer, it’s brutal,” Morales said. “Normally during the summer heat, people go to cooling zones like public libraries or pools. But unfortunately, due to COVID-19, none of that was available this summer and it was really hot.”

But working with the community to create a solution is really important, she said. Working with kids from the Latino nonprofit Providence Center in The Trust for Public Land’s development of the William Cramp Elementary and the José Manuel Collazo playgrounds in Hunting Park showed her the value of bringing young people into the process.

“They were really thrilled and happy to become part of something and to take ownership of their community,” Morales said.

Mosher said, through her own work, she has learned that the creative process can indeed be just as important, or even more important, than the final work. The process, she said, is where relationships are built and information shared, which makes the community more resilient to the impacts of extreme heat.

“They learn about solutions and hopefully also co-create solutions and responses that are unique to their own community and neighborhood needs,” Mosher said.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.