Airing the cleaned, pressed, and folded laundry of the American experience

The wardrobe of Maira Kalman’s mother tells the story of a 20th century American Jewish experience. You can take a peek inside.

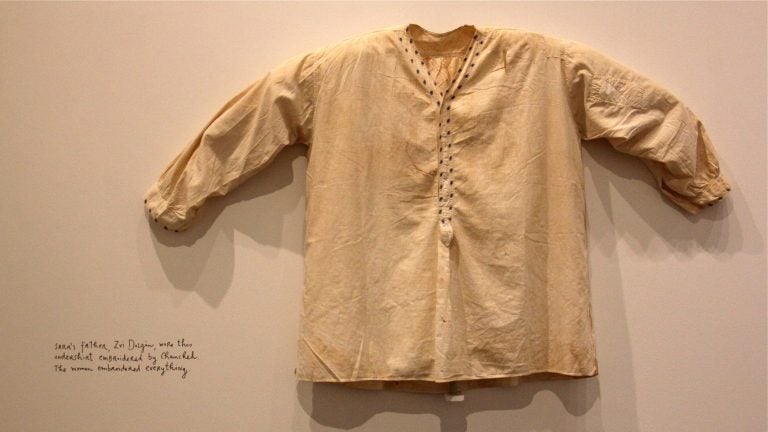

Sara's father's embroidered undershirt is one of many intimate objects and stories passed down through the generations. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From now until September, Independence Mall will feature a re-creation of a New York City apartment closet.

A wardrobe of neatly pressed, folded, and stacked clothes – all of them white – once owned by an elderly Jewish immigrant named Sara Berman is set up outside the National Museum of American Jewish History in “Sara Berman’s Closet” through August.

Sara Berman was not the kind of person who figures in history books. But, in her personal way, she was extraordinary. Born in Belarus where her family suffered under pogroms, Berman immigrated to Palestine in 1932 and witnessed it become Israel.

She married, had two daughters, then moved to New York. She and her husband moved back to Tel Aviv, and her children stayed in the U.S. At 60, Berman divorced and moved to a tiny apartment in the Village in Manhattan.

She was fastidiously neat. As an older woman, she wore only white clothes, which every day she meticulously ironed and folded and stacked in her closet.

“Growing up and going over to her apartment, we were already appreciating her closet as a masterpiece of art,” said Alex Kalman, her grandson. “Something that so simply and clearly expressed an idea and emoted a feeling.”

Berman died in 2004. Kalman believes her closet was perfectly expressive of Berman’s life of finding wonder and joy in small things. He re-created the closet at his Mmuseumm, a New York oddity of a curated gallery space inside a street-level elevator shaft.

It was then moved to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, opposite a re-creation of an 1882 dressing room used by Arabella Worsham, the wife of a railroad tycoon. There, the closet spoke to the difference between the wardrobes of a simple Jewish immigrant and the richest woman of late 19th century America.

The Jewish museum brought the closet to Philadelphia opposite the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall, to tell an altogether different story.

“Thinking about Independence Mall as the symbolic centerpiece of American independence, and her closet as a representative of her own independence,” said Kalman. “We think is the most interesting, surprising, absurd, true thing we could do with it.”

A closet resonant with ‘unwitting art’

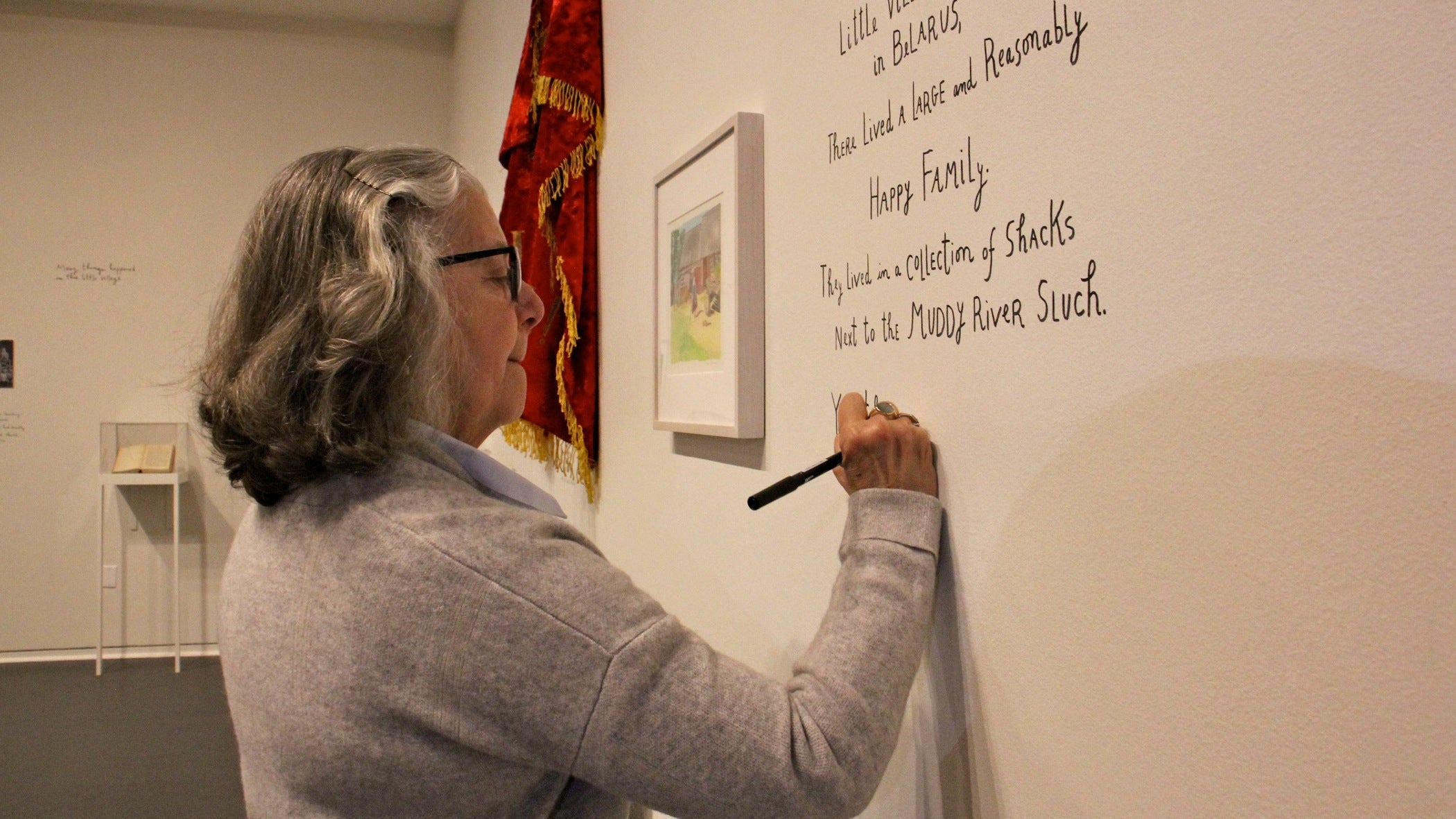

“Sara Berman’s Closet” is an exhibition both outside and inside the National Museum of American Jewish History. It was put together by both Kalman and his mother, Maira Kalman, a celebrated author and illustrator best known for her children’s books and New Yorker magazine covers. The two also wrote and illustrated a book of the same name.

“Not every closet tells a resonant story,” said Maira Kalman. “We thought this was an expression of art, of unwitting art.”

Inside the museum’s fifth-floor gallery, the Kalmans greatly expanded the narrative inside the closet to tell a story of the life of their mother and grandmother. The exhibition is full of whimsical anecdotes both true and untrue, digressions that go nowhere, and artifacts of a singularly eccentric, 20th-century life bouncing between Belarus, Tel Aviv, and New York.

Maira Kalman described the narrative as a “fairy tale.” There is a dream room: a clapboard shack filled with goose feathers and crowned with the lyrics to a Polish nonsense children’s song. The exhibition includes big things, such as the murderous pogroms of World War II, and little things, including Berman’s sister Shoshanna cutting her own bangs.

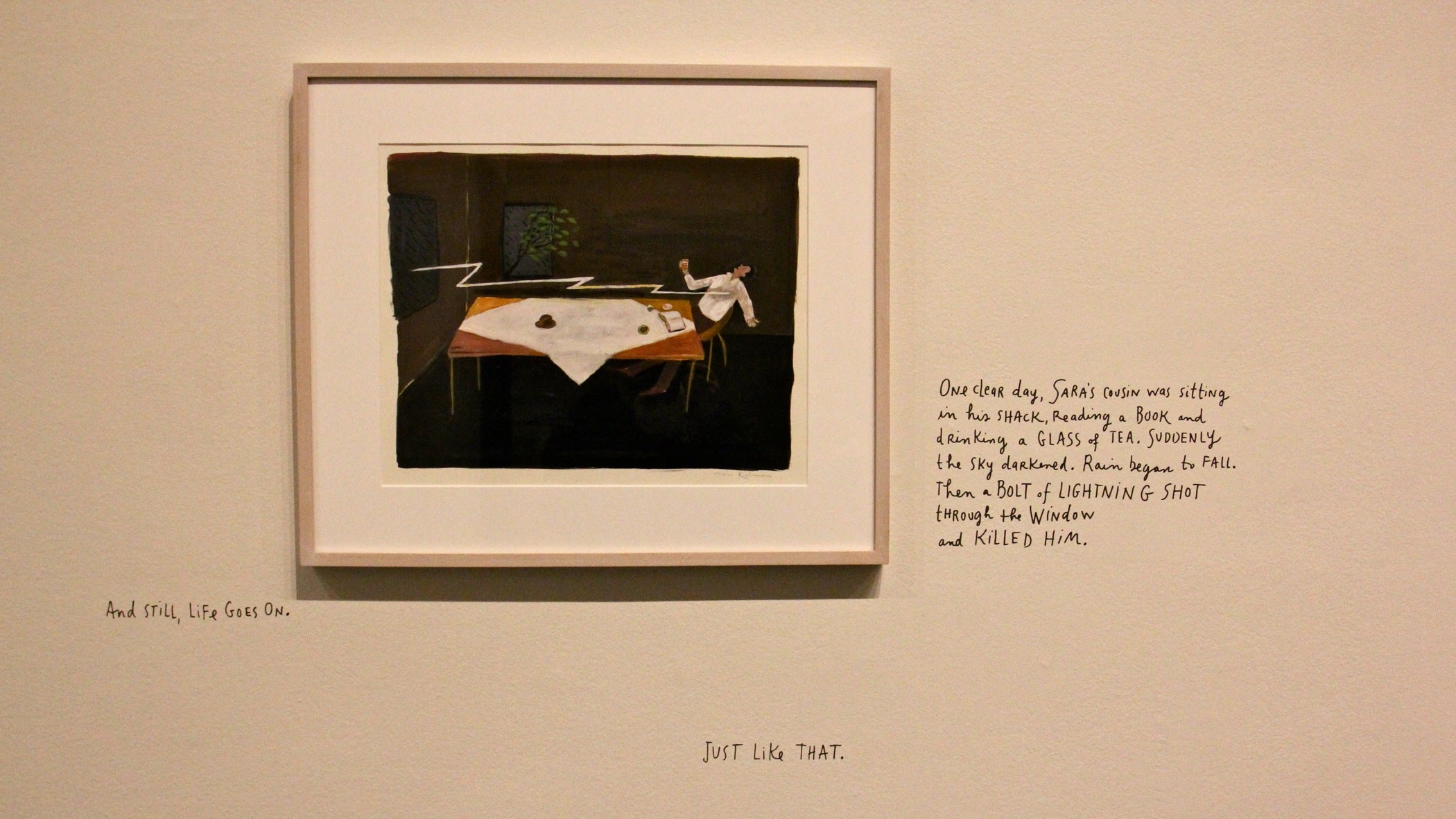

There is the story of a cousin who was sitting at his kitchen table one day, drinking tea, when a freak lightning bolt came through the window and killed him. That one is true.

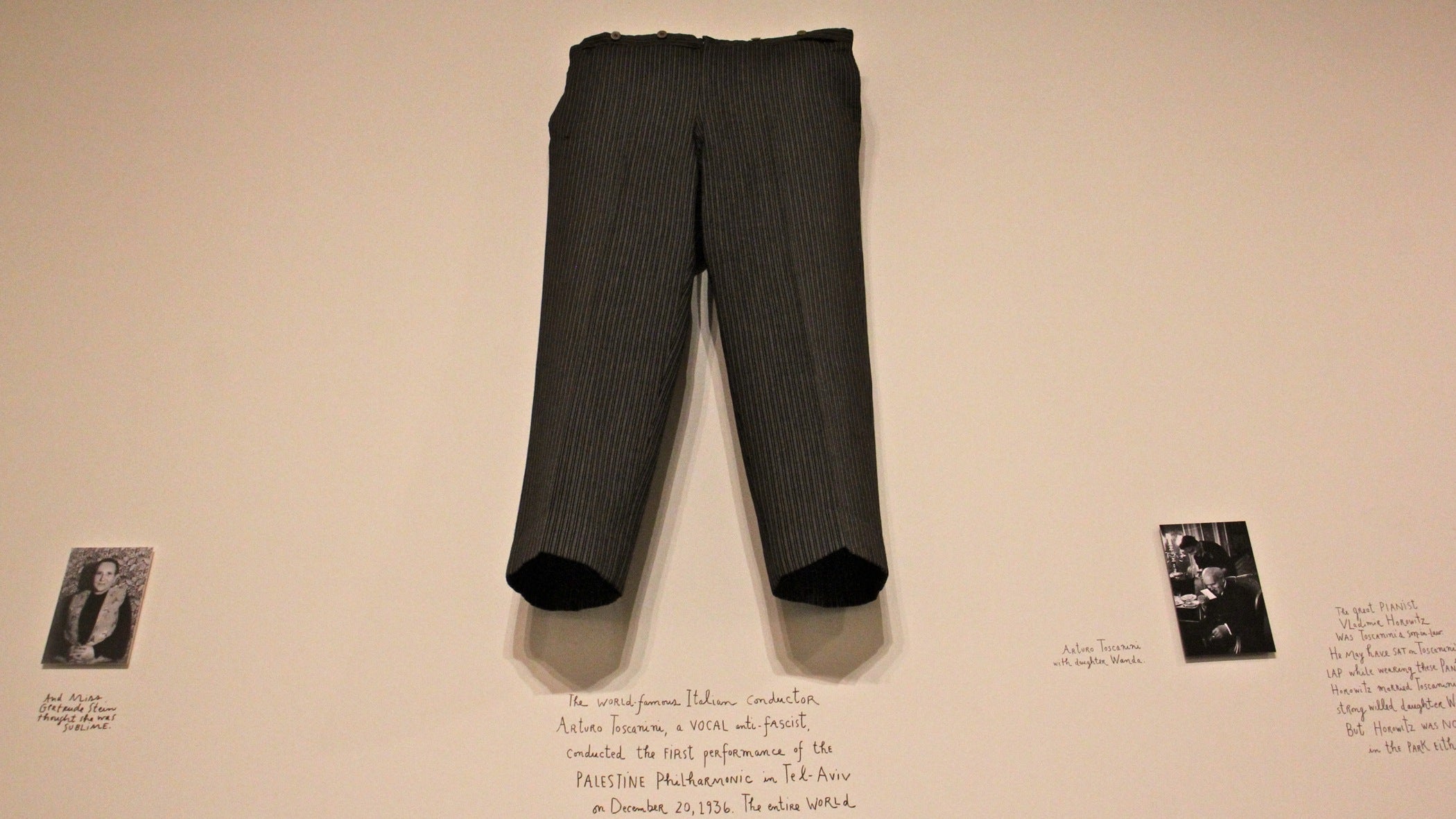

It also includes the story of how Berman, as an exceptionally attractive young woman, was courted by the famed conductor Arturo Toscanini. That one is not true. Nevertheless, a pair of Toscanini’s pinstripe trousers — Maira Kalman won at auction — are on display.

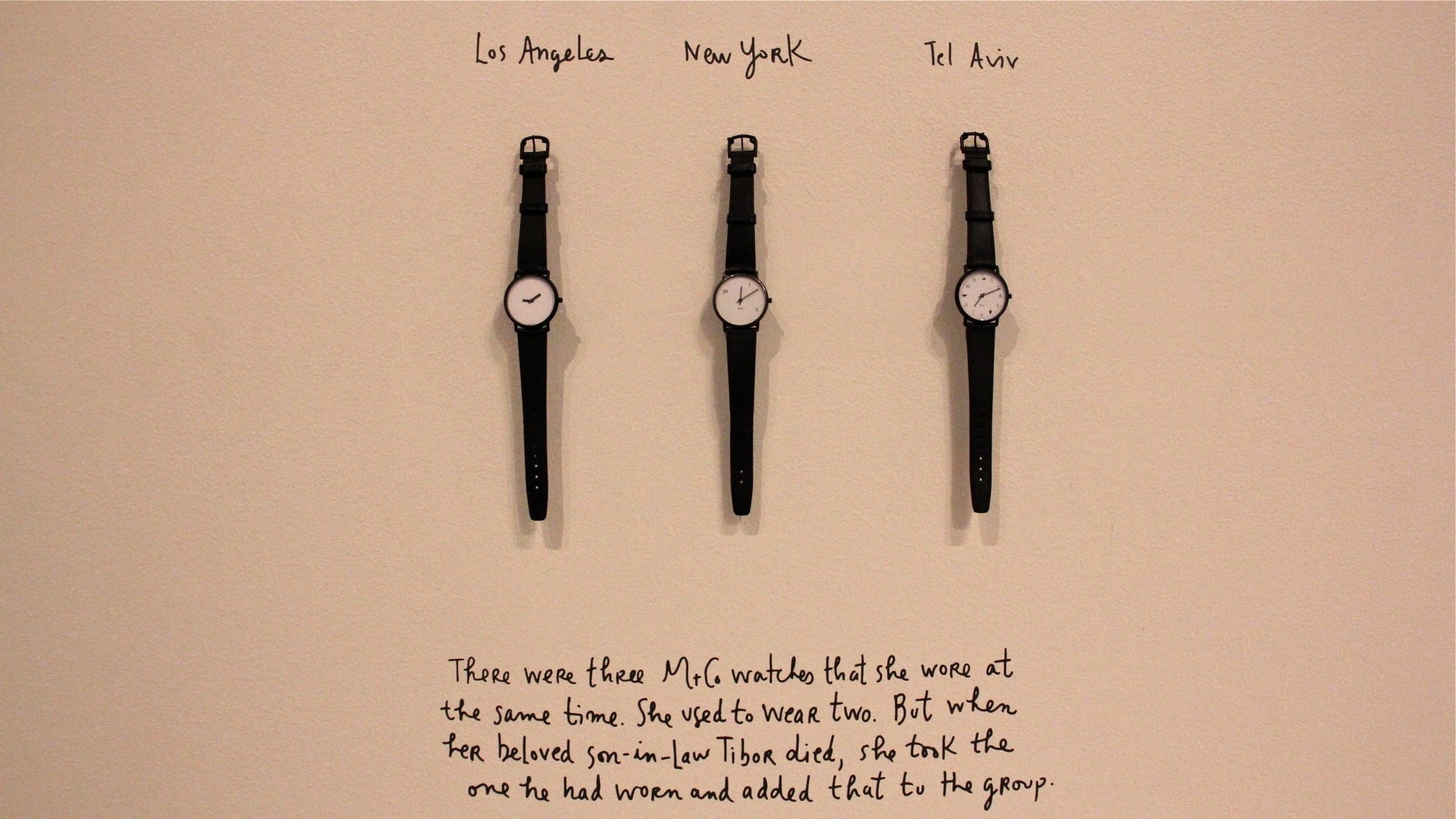

Berman liked to wear three watches simultaneously on her wrist, each set to a different time zone: She had one daughter in New York, another in Los Angeles, and an ex-husband in Tel Aviv. All three watches are on display.

A handful of wires spills out of the exhibition wall, apropos of nothing.

Orderly closet frames untidy story

Although the exhibition is linear, moving from birth to death (video footage shows Berman on the last day of her life, eating a lemon ice while wading in the surf on a Tel Aviv beach), the narrative is intentionally sloppy and unreliable. It has the feel of a stream-of-consciousness scrapbook, in contrast to Berman’s meticulously maintained closet.

“I do know, of course, the story of a human life is very sloppy, inconsistent, emotional highs and lows, confusions and digressions,” said Maira Kalman. “In counterpoint to this very meticulous closet is an actual story of an actual life, which would have all the messiness that a life does.”

Both of the Kalmans say that’s the way Berman would have wanted it, folded underwear and all, because the family “hates sentimentality.”

“We think she’s hovering over and laughing in amazement,” said her daughter. “Amazed, incredulous, and delighted.”

Nowhere in the exhibition does any of the material explain that its subject is related to the curators. Although Maira Kalman appears in one photo as a 5-year-old girl, she is not named.

“Our relationship with her isn’t the compelling element of her story,” said Alex Kalman. “We want to free her of our relationship and let her exist as an individual who lived a life”

Maira Kalman is particularly excited to know her mother’s intimate clothes will be part of the very public Fourth of July celebrations on Philadelphia’s Independence Mall. She plans to hand out lemon ices to passers-by to celebrate the memory of her mother’s last day.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.