After Trump-era rise in citizenship petitions, naturalized immigrants may be force at polls

Citizenship petitions spiked around Trump's election. Will naturalized immigrants be a midterm election force?

Listen 4:40

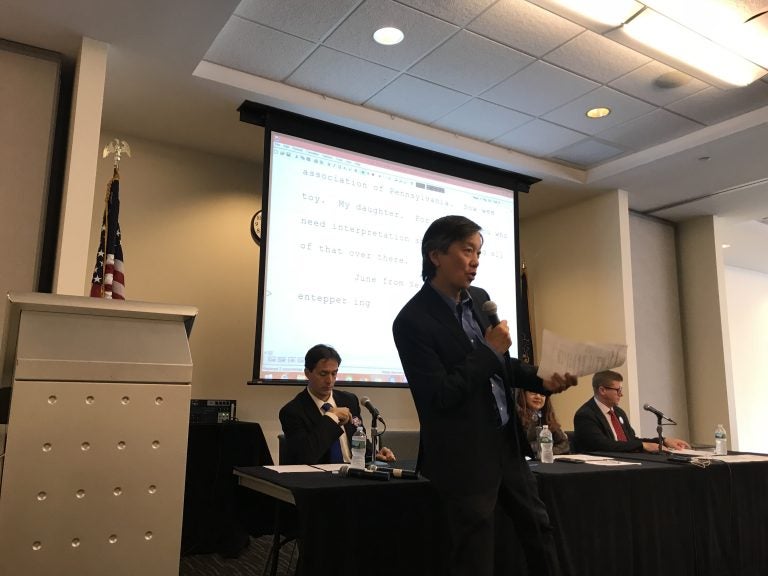

Andy Toy, on behalf of United Voices of Philadelphia warms up the crowd before a candidate’s forum geared towards immigrant voters. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

On a gray October Saturday, candidates for the Pennsylvania State House gathered in a community college classroom in Northeast Philadelphia. They had come for a forum hosted by nearly two dozen civic and immigrants rights groups, geared for outreach toward voters in two districts in the immigrant-dense northeast corner of the city.

“Let’s say you’re Latino, Asian, Arab-American, Caribbean, Muslim, whatever other new immigrant. We make up 25 percent of Philadelphia, and we should be having more of a voice in what happens here,” said Andy Toy, on behalf of United Voices of Philadelphia.

About one in four Philadelphians is a first- or second-generation immigrant, according to Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative. In the audience of about 50 people, older folks nodded along, wearing earpieces so they could hear Toy’s words in translated into Nepali or Spanish.

While Toy referred to immigrants in general, the event was aimed at a smaller group — those who can vote. Nationally, naturalized immigrants count for about 9 percent of eligible voters. In 2016 and 2017, new petitions for U.S. citizenship spiked, rising by 25 percent.

Increases in citizenship petitions are common ahead of a presidential election; however, the sudden and sweeping immigration policy changes in 2017 — such as the travel ban — kept applications coming at a higher rate after President Donald Trump took office.

With many of those applicants now naturalized (while others wait amid a mounting backlog), whether they’ll turn out in force could have an impact on the Tuesday midterm election.

At the candidate forum, audience member Wasif Qureshi said Trump’s 2016 campaign promise of a Muslim registry brought back painful memories.

“I came here to this country in 2000, and then 9/11 happened in 2001. We had to get ourselves registered. Many people don’t know that,” he said.

Qureshi, a cardiologist with a medical practice in Delaware, said becoming a U.S. citizen and connecting with the political process were ways of dispelling a double standard he sees in the U.S.

“You will put your life in the hands of a Muslim physician, but you can’t tolerate a Muslim neighbor. I think that’s ridiculous,” he said. He’s now on the board of Emgage, a group focused on connecting elected officials with their Muslim constituents.

National groups including the United Voices of America and the New Americans Campaign, as well as local immigrant advocacy groups, have been encouraging naturalization and civic engagement among eligible immigrants.

The process

To apply for naturalization, immigrants must have had a green card for five years, speak basic English, and have “good moral character” among other criteria, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Those efforts try to counteract a general trend — that naturalized citizens vote at lower rates than U.S.-born citizens of the same immigrant background.

However in 2016, naturalized Asian and Latino voters turned out at higher rates than their U.S.-born counterparts, according to the Pew Research Center. Differences in voter turnout between naturalized citizens and U.S.-born citizens are largely eliminated once naturalized immigrants register to vote, according to a study by the University of Southern California.

Whether someone who becomes a citizen wants to take that next step may have something to do with the reasons they wanted to naturalize in the first place. Along with the ability to vote, fear and family are two other big drivers of citizenship applications, according to Mary Clark, who runs the citizenship support programs for HIAS Pennsylvania.

“One of the most consistent reasons given is security, wanting to feel a greater sense of security in the U.S., and not feeling comfortable travelling,” she said.

Whether that added security will translate into turnout is not clear. Figuring out the U.S. political landscape and voting system can be a challenge for new citizens, according Sundrop Carter, executive director of the Pennsylvania Immigration and Citizenship Coalition, which registers voters at its naturalization ceremonies.

“We get a lot of questions, like, ‘Why do I have to put down a party? What happens if I don’t register to vote? What happens if I do register to vote?’” she said.

New citizens are less likely to vote than those who naturalized a while ago. Even so, the University of Southern California study found that civic participation by newly naturalized immigrants can influence how candidates talk about immigration. It also has the potential to tip the balance in races in battleground states such as Pennsylvania, Florida, and Nevada.

Will they or won’t they?

But that’s only if potential voters — such as Magda Flores and Carlos Barrero — choose to go to the polls. Flores, trained as an accountant, and Barrero, a professor at the School of Pharmacy at Temple University, are from Colombia. This year, they became U.S. citizens after 12 years in this country in order to give their oldest daughter more opportunities.

Both have registered to vote, but Barrero answered shyly when asked what political issues he cares about.

“I have my own ideas of that, but I don’t think it will be good … it would be good, it will matter a lot if I’m going to run for president, but right now, I don’t think I am allowed,” he said with a laugh, deflecting.

The impact of Barrero, Flores, and other potential voters Tuesday may come down to whether such hesitance melts away once the voting booth curtain closes behind them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.