After leading British Museum, scientist in his element at Chemical Heritage Foundation

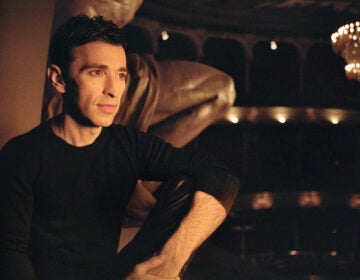

Chemical Heritage Foundation president Robert Anderson formerly directed the British Musuem. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia, a relatively small institution focused on the history of science, has a new permanent director — Robert Anderson — who who used to run one of the largest museums in the world.

The British Museum is not just a massive institution housing 13 million objects and welcoming 6.7 million visitors a year; it also represents the cultural legacy of what was once a global empire.

By comparison, the Chemical Heritage Foundation hosts about 30,000 visitors a year, with an archive of about 150,000 objects related to the history of chemistry, ranging from original 15th century alchemical manuscripts to midcentury toy chemistry sets.

Anderson ran the British Museum from 1992 to 2002, a turbulent decade for the institution. It experienced steep government budget cuts resulting in major staff layoffs, as well as the development and construction of an architectural wonder — the $145 million Great Court, the largest covered plaza in Europe.

Anderson was also at the center of the still-unresolved debate over whether to return the Elgin Marbles, a set of ancient sculptures, to Greece. He became involved in an internal restructuring that split his duties with a management director — a government mandate that ended badly.

“The other thing is that we kept getting diplomatic visits from people,” said Anderson. President George W. Bush, “for example, came to the British Museum to spend two hours with us. Which was fine, but it took three weeks of preparation to deal with the security issues.”

Before Anderson was a museum director, he was a scientist. While running the British Museum, he kept up his research at night and published papers on the history of chemistry.

He has researched — among other things — the work of Joseph Priestley, the British chemist who discovered oxygen and later became a Unitarian preacher in Pennsylvania; phlogiston theory, a 17th-century idea about the chemistry of burning that has since been superseded; and the relationship between textile industrialists and academic chemists in 19th-century Scotland.

Anderson,a board member of the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia for 10 years, last summer was tapped to step in as interim director. After six months, he accepted the job permanently.

On a certain level, it’s a quieter job than running the British Museum in the world. Here, his research is more in line with the mission of the organization he heads.

“You say quieter. Intellectually, it’s not quieter,” Anderson said in an interview in his office overlooking Independence National Historic Park. “There are some extremely good people working here who come up with bright ideas all the time. They have to be debated to see if they can be put to practical use.”

There is upheaval ahead for the Chemical Heritage Foundation. It recently merged with the Life Sciences Foundation in California, which will expand the focus of the foundation, necessitating a name change and a complete rebranding.

“Chemistry has never stood still. It’s always changing,” said Anderson. “It has changed toward the biological sciences in the last few decades. We want to be where the action is happening.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.