After decades of turmoil, 52nd Street is getting a new lease on life

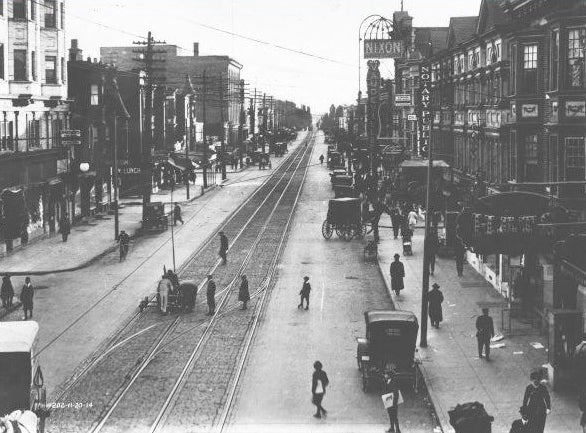

It used to be West Philadelphia’s main street. A regional shopping destination that was so vital tourists in Philadelphia would make a point to visit and check out the shops, sample the vibrant street life.

Yet in recent decades, the 52nd Street corridor has fallen on hard times. Customers left for suburban shopping malls. Businesses moved out. Old buildings deteriorated. The iconic canopies near the Market-Frankford El became coated with a sheen of grime.

Then came the El reconstruction project in 2000, which closed Market Street for nearly 10 years and caused massive disruption on the corridor, driving away customers and causing even more retail stores to fail. Throughout the entire El reconstruction area, 47 businesses closed from 2000 through 2009, according to The Philadelphia Inquirer, leaving millions of dollars on the table by forcing neighborhood residents to do most of their shopping elsewhere.

A 2006 Planning Commission study found a staggering $160 million in unmet demand residents have for goods and services in the neighborhoods around the El. And another study found that 52nd Street in particular was failing to capture important local consumer dollars, including $26 million for full-service restaurants and $12 million for furniture stores.

Now, 52nd Street may be getting a new lease on life.

A coalition of city officials and the local business community is trying to breathe new life into the corridor, bringing in a new development plan and promising to inject much-needed capital into the businesses that remain and potential new ventures.

The goal, in short, is to upgrade 52nd Street’s ambience with facade improvements and regular sidewalk cleaning, attracting more upscale businesses and turning the corridor into a regional hub once again.

But first, everyone on the corridor had to start getting along.

Getting Everyone Talking

That wasn’t easy. Commerce on 52nd Street has been traditionally split between storefront businesses and the street vendors who line the blocks near Market Street. The two groups haven’t always seen eye-to-eye, each group worried that the other was stealing its business.

Add to that clear racial and ethnic tensions, and you get a volatile mix. According to a 2009 presentation by the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians, more than half of the 200-plus corridor merchants are foreign-born. Forty percent of the merchants have East Asian roots, and there are sizeable minorities of Caribbean and South Asian businesses. And the city has only recently been able to start a dialogue with an association of Korean businesses on the corridor.

The tensions associated with doing business were apparent in a recent interview with Azizuddin Muhammad Abdulaziz, a 52nd Street vendor and president of the Philadelphia Vendor Association. He blamed the corridor’s decline in part on immigrants ― especially Koreans ― who opened stores that sold the same kinds of products as the vendors.

“They copied whatever we sold on the street,” he said, adding that “they all were after the same dollars.”

At the same time, the storefront owners resented the legal gray area the vendors inhabit ― they aren’t licensed to do business, but the city won’t kick them out.

When the Commerce Department began making plans to transform the corridor, moves to legitimize the vendors’ presence ran into opposition from store owners who “feel [the vendors] have been rewarded for the bad behavior,” said Dr. H. Ahada Stanford, neighborhood markets manager, who is spearheading the project for the city.

The vendors and storefront owners ended up working through most of their differences ― even if there are some residual bad feelings ― in part because the city got the two groups talking to each other.

And the plan that emerged focuses on priorities that benefit all sides.

Both the business and vendor associations want to attract clients looking for upscale products to the corridor. Muhammad remembers that when he started vending on 52nd Street in 1988, he was able to sell women’s suits. Now, he sells cheaper casual wear. And both groups of merchants see a combination of corridor cleaning and upgraded facilities ― facade improvements for the storefronts, new carts for the vendors ― as the key to regaining that market.

First, though, the city had to win over the storefront owners and vendors.

The 52nd Street Business Association, which represents storefront owners, wanted help to recover from the El reconstruction but thought the city’s plans weren’t what its members wanted. “Sometimes it’s very difficult to bridge the gap in having people understand what a community is saying,” business association president Shirley Randleman said. The business association also got frustrated at how long it took to finalize plans and line up financing for improvements. “Can we simplify this process?” Randleman asked. “It’s not rocket science.”

The vendors, for their part, were afraid the city was trying to kick them out by targeting the corridor’s iconic canopies for demolition. Erected in the 1970s with the support of Lucien Blackwell, they had long provided the vendors shelter from the elements. The city had decided it would cost too much ― $1.5 million ― to refurbish them, and a Planning Commission study said taking them down would have the added benefit of stimulating storefront owners to renovate their facades, which were blocked from view but falling into disrepair.

Stanford thought she had an agreement with the vendors to move them to a vacant lot at 51st and Market after the canopies came down. The vendors didn’t see it that way. They tied themselves to the canopies one night in December 2009 when demolition crews showed up to take them down. “The community wasn’t asked first what they felt about it. They just tried to sneak in and tear it down,” vendor Khalil Muhammad told 6ABC at the time.

The community opposition brought Stanford and community leaders back to the table, delaying plans on the corridor another year and a half. But in the end, Stanford said the delay was worth it. Azizuddin Muhammad had been trying to convince his fellow vendors for years to band together, but they had mostly ignored him ― until the city tried to take down the canopies. The new vendor association was able to sit down with the city and plot a future for the corridor that kept the vendors happy. “That was … real cool,” Stanford said.

Creative financing

After years of discussion, the city and neighborhood groups finally settled on a concrete plan to revitalize the corridor after the canopies came down.

First, the city was willing to put money into facade and streetscaping improvements. Storefronts, especially those covered by the canopies, are in pretty poor shape. The city and business association think the poor quality of building stock keeps away upscale shoppers and retailers.

The city also teamed up with the Welcoming Center to provide business development support and found money for economic development loans for the businesses. Instead of relocating the vendors, they’re going to get appropriate licenses to remain on the corridor.

City Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell, who represents 52nd Street, introduced a bill March 3 which is currently in committee, that would legalize sidewalk vending along 52nd Street and limit the number of vendors to 56 from Arch Street to Walnut Street ― a key goal of vendor association president Muhammad, who’s afraid too many vendors would water down profits. Current vendors would get slots based on the length of time they’ve been active on the corridor, and a lottery would fill any open spaces. (Blackwell’s office, which has been involved in negotiations over the development plan, didn’t return a call for comment.)

The city is also working with the vendors to design and build uniform vending carts and set up a permanent storage space for them.

Finally, everyone agreed that establishing regular cleanups of the corridor would attract more foot traffic and create a welcoming environment for new businesses.

While setting these goals was a good first step, figuring out how to pay for them took creative thinking.

The canopy demolition ― accomplished last month ― was paid for by money from the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp.’s ReStore Philadelphia Corridors program.

The Streets Department and Pennsylvania Department of Transportation agreed to pay for lighting, traffic and curb cut improvements through the corridor and on Market Street, in part using money left over from the El reconstruction.

Other aspects of the plan are more difficult to fund because the city doesn’t have money specifically set aside for the type of improvements Stanford and the community want to make. For instance, though the city has a program to fund individual facade improvements, it’s not designed to cover an entire corridor’s worth of businesses.

So Stanford and Commerce Department project manager Aissha G. Herring-Miller cobbled together money from the Community Development Block Grant and technical help from the Community Design Collaborative to jumpstart the process.

On the cleaning front, Mercy Hospital donated a street cleaner to the business association, and Stanford is hoping to tap into part of a $70,000 economic empowerment zone grant that includes the corridor. The business association and the city also have to agree to a regular source of funding ― in part from business association membership dues ― to keep the cleaning going.

Stanford says it’s too early to tell how much money will be channeled to the corridor, and from where. Many details, such as financing to build the new vendor carts, are still being worked out.

Despite the slow pace of the work, Stanford hopes the corridor will start seeing improvements within a year.

And while it might take longer to achieve the business association’s goal of attracting high-end fashion boutiques and a big box presence like Staples, Stanford said the business community has begun to realize that change is on the way. An owner of a key parcel recently became current on his taxes, and city property records show that a handful of parcels along the corridor have changed hands over the past two years.

If everything comes together, 52nd Street may be only the beginning. Stanford wants to use the lessons learned through this revitalization effort to help other struggling commercial corridors in West Philadelphia. Next on her plate: the 60th Street shopping district and Market Street under the El.

Contact the reporter at acampisi@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.