A Philadelphia attorney bought a $3,500 gun safe in response to Pa.’s new domestic abuse law

Some attorneys say storing guns brings too much risk or is just too big of a hassle.

Philadelphia's Criminal Justice Center. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This story originally appeared on PA Post.

—

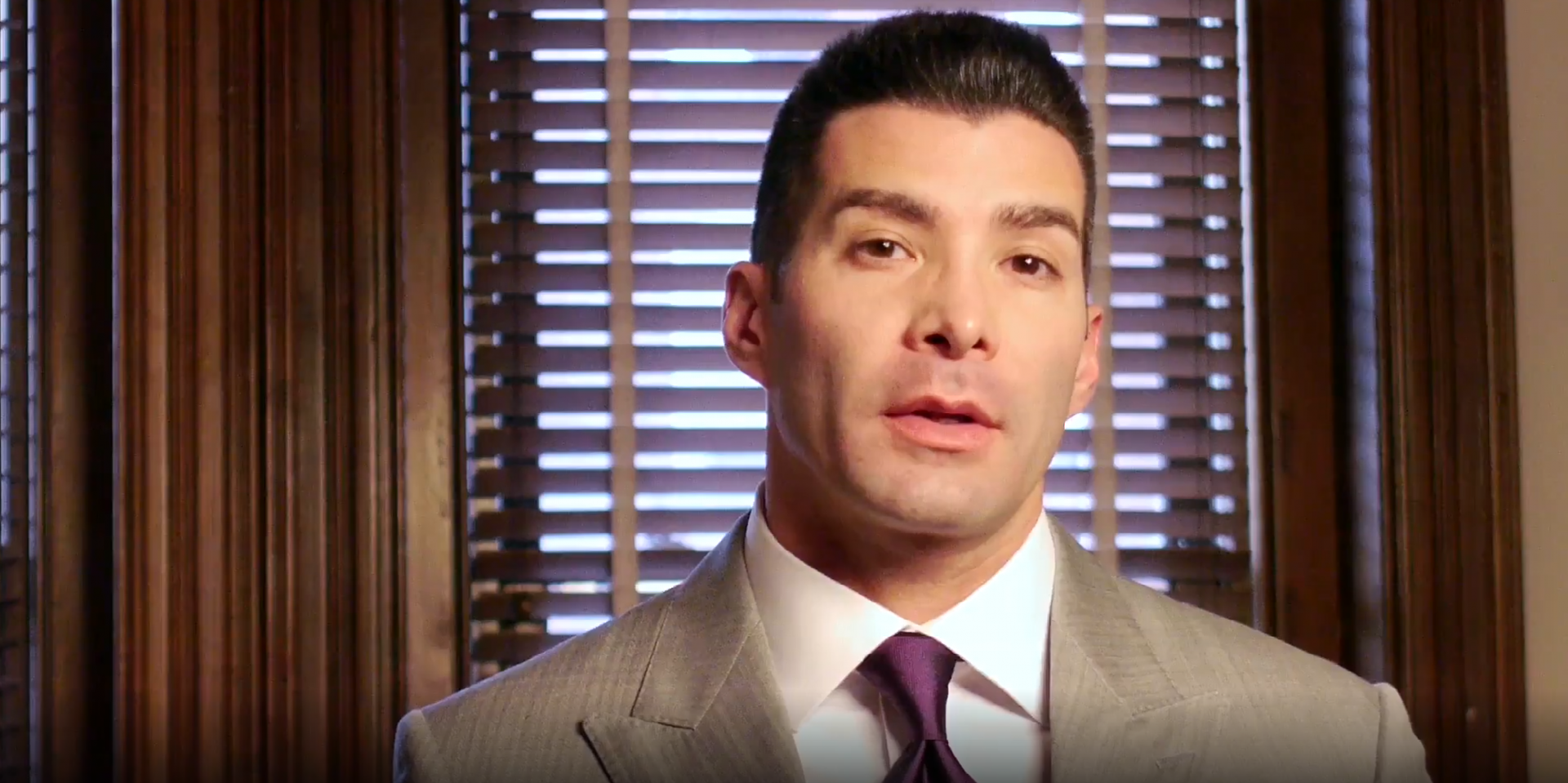

Joseph Lento went to law school in Philly and his main office is there.

He has a “Rocky”-inspired bio video on his website, complete with him drinking raw eggs from a glass and trekking up the Philadelphia Museum of Art steps.

“The right attorney can make all the difference in the world in a person’s life,” Lento says in the video.

And there’s a new way Lento is willing to make a difference in the lives of his clients: By storing their guns.

Lento is responding to a change in Pennsylvania law, one that limits who can hold onto the guns that alleged domestic abusers have to give up.

Under the state’s new Protection from Abuse Act, which took effect April 10, when defendants in protection-from-abuse cases have to relinquish guns, they can no longer hand them over to a friend or family member for safekeeping.

Instead, defendants have to turn their guns over to a law enforcement agency, a licensed firearms dealer, a commercial armory — or an attorney, such as Lento. Those PFA orders can last up to three years.

Earlier this month, Lento made what he called a “significant investment” for his law firm.

He spent about $3,500 on a gun safe. It can hold about 50 guns — depending on the type.

But some lawyers contacted by PA Post aren’t willing to take on that responsibility, saying it’s too much of a risk, or a hassle.

Why attorneys don’t want guns

Michael P. Gottlieb, an attorney in Montgomery County, said he is a member of the National Rifle Association and “every pro-gun organization that I know of in Pennsylvania.” He shot competitively until a shoulder injury sidelined him.

On his website, he promises to “fight to restore your rights when a firearm has been taken away unjustly.”

But he doesn’t want to store guns for clients.

“I’ve got to jump through a whole bunch of hoops to be able to do it,” Gottlieb said.

A large and secure safe would cost a few thousand dollars, he said. And if the police had reason to believe one of his clients’ guns was involved in a crime at some point, they would obtain a search warrant to take the gun from his office.

“What if I’m not here to open the safe? Well, guess what, they’re not coming back,” Gottlieb said. “They’re going to torch it open right on the spot.”

Todd Spivak, an attorney in southwestern Pennsylvania, specializes in PFA cases. He has a section of his website dedicated to frequently asked questions about PFAs.

He is not going to store guns for clients.

“This seems well outside the scope of what we signed up for as attorneys,” Spivak said. “…When I first learned of this new law, I thought it was bizarre, frankly.”

Philip Kline, a Bucks County attorney, specializes in gun cases.

He thinks, on a practical level, guns are more likely to wind up with sheriff offices because of timing challenges. Kline also said he would have to charge clients for the time it takes to handle any paperwork connected to storing guns.

Marc Scaringi, whose Dauphin County office has photos of Scaringi with Republican President Donald Trump, said his firm has probably handled hundreds if not thousands of PFA cases over the years.

Scaringi has a concealed carry license that can be useful for arranging the legal transfer of weapons for clients.

But he has a lot of concerns about the idea of storing guns.

“I have liability concerns. I mean, we’re a law firm,” Scaringi said. “We give legal advice. We’re not in the business of storing firearms.”

Why lawmakers made attorneys an option

For years, domestic violence advocates urged for changes in the PFA law, and they were particularly critical of the provision that allowed defendants to hand over guns to friends or family members for safekeeping.

They pointed to the death of 2-year-old Michael Ayers in Huntingdon County and other deaths as examples of the danger of allowing a family member to keep someone’s guns.

In 2017, when state Sen. Tom Killion introduced legislation to change the PFA system in Pennsylvania, the bill said defendants could give their guns to a law enforcement agency or a licensed dealer.

But Shannon Royer, Killion’s chief of staff, said the proposal was changed after a long period of discussion with gun rights groups and other stakeholders.

Royer said there was concern about “guns that were of tremendous value” and whether they would be damaged while being held by a sheriff’s office or other law enforcement agency. As a compromise, attorneys and commercial armories were added as an option.

Domestic violence advocates didn’t object, Royer said, and the changes passed as part of Act 79.

Joshua Prince is a prominent firearms attorney in Pennsylvania. Right now, he is seeking to overturn gun restrictions in Pittsburgh.

In an email, Prince said there a number of things for attorneys to consider when it comes to storing guns, including insurance coverage in case firearms are damaged.

While Prince has served as a third-party safekeeper before, he said there are “very few circumstances” where that actually makes sense.

Jonathan Goldstein, a firearms attorney in the Philadelphia suburbs, was involved in the negotiations over Act 79. He said having an attorney available as an option could be useful if, say, a person needs to relinquish guns late on a Saturday evening.

“PFAs move at a very high velocity,” Goldstein said.

He said attorneys can be a “fast, reliable, safe, easy way to put those firearms into the hands of someone trusted and to get them out of the hands of the purported abuser.” Attorneys are sometimes given cash, documents and artwork to hold onto for clients, he said.

Goldstein said he has served as a third-party safekeeper before, although he declined to go into details of how many guns he had stored or the logistics of how he stored them, citing security concerns.

Goldstein said attorneys generally have insurance to cover malpractice claims and claims related to the care of customer property. He said gun owners often have insurance in place to protect their gun collection.

“I would say insurance is not really a big factor in the analysis,” he said.

Lento, the Philadelphia attorney who bought a $3,500 safe, said he thought about potential risks. But he sees benefits to all sides in having an attorney hold onto the guns.

Defendants can sometimes be reluctant to give up their guns. And Lento thinks some clients might be more likely to give up guns more quickly to an attorney than to, say, a sheriff’s office. So that, he thinks, benefits the plaintiff.

Meanwhile, Lento thinks defendants can have more peace of mind that their guns are being taken care of. Lento has heard horror stories about a sheriff’s office disposing of a gun before the defendant could get it back.

Attorneys are already given a lot of trust. And he thinks attorneys can be trusted to not give guns back when they shouldn’t.

“An attorney worth his salt is going to live up to that obligation,” Lento said.

A person in Lento’s office will be responsible for making sure the firearms are properly maintained, while also tracking who they belong to and when they can be returned.

As of late April, no one had relinquished guns to Lento under the new law, and he was still working on getting the safe set up.

But he doesn’t plan to charge clients extra for storage.

“It doesn’t require much on my part, other than say, just an initial investment and some ongoing oversight,” Lento said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.