A look at Inovio’s Philly local coronavirus vaccine-in-progress

The vaccine developed by the Plymouth Meeting firm and Wistar Institute researchers finished Phase I trials and is moving to an accelerated Phase II/III.

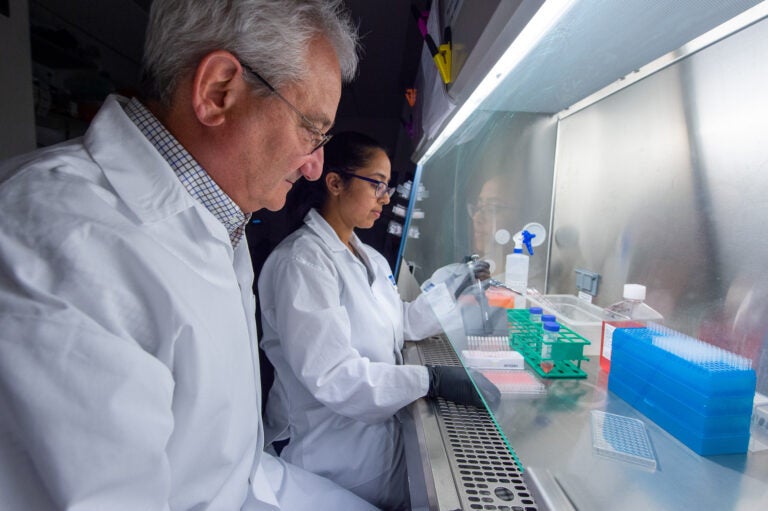

Dr. David Weiner (left), director of Wistar’s Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center, and Dr. Ami Patel, research assistant professor, work on synthetic DNA technology prior to the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. (Courtesy of The Wistar Institute)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

Operation Warp Speed, the federal government’s multi-agency push to develop a COVID-19 vaccine, is promising to provide 300 million doses by January 2021. That means funding for several of the top candidates. Moderna, one of the leaders of the pack, is already in Phase III trials after creating its first vaccine in a record-breaking 42 days.

The New York Times vaccine tracker lists more than 165 vaccines, with 28 being tested in humans. Those being developed by Pfizer, the University of Oxford in conjunction with AstraZeneca, Chinese companies Sinopharm and Sinovac, and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia are all in Phase III trials. (Thomas Jefferson University, with a vaccine designed by Matthias Schnell, announced a partnership in May with Bharat Biotech, an Indian biotech company; they expect to reach clinical trials by December.)

At Plymouth Meeting-based Inovio Pharmaceuticals, the vaccine known as INO-4800 has just finished Phase I trials and is moving to an accelerated Phase II/III, in which it will be ascertained whether the treatment is effective and better than what might already be available.

For Kate Broderick, Inovio’s senior vice president for research and development, the search for a COVID-19 vaccine has meant seven months of nonstop work, but she’s seeing signs of hope.

“I genuinely feel that every day that there’s an enormous responsibility on my shoulders, but I’m really encouraged,” she said. “I do hope that the public can see some of the data that’s coming out and see that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Many of the vaccines now in development use proteins, little bits of the novel coronavirus, or even a dead version of the virus. Inovio’s uses DNA. When people receive the vaccine, they also get little pulses of electricity (through special needles) that push that DNA into their cells.

DNA floating around in the body’s cells is just a normal part of life — it is “read out” by our biological machinery and turned into proteins that build cells and structures, allow for communication, and generally make life possible. When the DNA added into the cells is read out, the body produces its own vaccine, which then goes on to alert the immune system.

All vaccines, like all medications, have a risk of some level of side effects, and the severity can vary significantly. Phase I clinical trials aim to prove the safety of a treatment using a small group of people. Inovio reported that its vaccine was safe, meaning development can move forward. (Although Inovio’s COVID vaccine is very new, its special needle and DNA technology are ideas that the company has used and tested in other projects.)

“You’ll have some mild injection site pain, but you get that with normal vaccines,” said Ami Patel, a research assistant professor at the Wistar Institute who has been involved in developing Inovio’s COVID-19 vaccine since January. “You don’t have a lot of those other symptoms that are sometimes associated [with commonly administered vaccines], like fevers and headaches.”

The Inovio vaccine, Broderick said, “almost tricks your body.” If other vaccines are bringing you a sample of food to try, Inovio is just dropping off the recipe, and that causes fewer initial side effects. As to what is getting stuck in your arm, “it’s really just DNA and water and a tiny bit of salt,” she said.

Getting to an immune response

Phase I trials aren’t just about safety. They also give researchers the first information about how well a vaccine works in humans — before Phase I, most vaccines have only been tested in animals. In a June 30 press release, Inovio said that 94% of those people immunized “demonstrated overall immunological response rates.”

The idea of a vaccine is to encourage the body to produce antibodies, but it is not yet known how many antibodies a person needs to produce to be protected. That’s what Inovio hopes to learn in the next phase of trials, Broderick laid it out this way: “ln this summer period, we can start our Phase II/III trial, which is going to allow us to really ask the question in human beings, ‘Does our vaccine protect from COVID-19 disease?’”

There are three goals for a good vaccine, she said: “One, that the vaccine is safe; two, that it’s effective; and three, that it’s also got long-lived protection.” A good vaccine makes your body create antibodies. These antibodies let you identify and fight off whatever the vaccine is against, in this case, SARS-CoV-2. With a really good vaccine, the antibodies stick around as long as possible, which means you’re protected for longer.

“Nobody goes and gets a vaccine and then immediately is infected by the virus,” said Broderick. “Much more likely, it will be a few months since a vaccine, or six months or a year, before you actually encounter the virus.”

In late July, Inovio released data from its durational primate trials. Inovio researchers gave a group of rhesus macaques, a type of monkey common in medical trials, two shots of the COVID-19 vaccine. Almost three months after the last shot, the scientists infected the monkeys with the coronavirus and found that the immunized macaques had less virus in their lungs and noses. That speaks to the third of Broderick’s goals: For a vaccine to be effective, vaccinated people need to be protected months after they were first vaccinated.

Moderna, the Massachusetts-based biotechnology company and vaccine frontrunner, completed a similar trial at the end of July, testing immunity four weeks after vaccination. Representatives for the firm did not immediately respond to a request for an interview for this article.

“In the sense of what each vaccine is doing, I think there is maybe a little bit of sort of friendly competition between all of the … different varieties of vaccine companies that you see,” said Patel. “ But what I think we’re all seeing, as a general community — vaccine, as well as just medical and scientific communities — [is] that everybody is really sharing the information that’s coming out.”

How much for all this?

What about some information that isn’t being shared as readily — cost? With everything on the line, COVID-19 immunity feels a bit like a priceless commodity.

Pricing a vaccine is not as complicated as creating one, but it isn’t far off. To beat the coronavirus, the vaccine needs to be cheap and available in large quantities so that everybody gets a dose. But it also needs to turn enough of a profit to cover the cost of development and manufacturing. On an Aug. 5 investors call, NPR reports, Moderna’s CEO said the company had already made deals with some countries at $32 and $37 a dose for small orders, with lower prices for larger quantities.

How is Inovio doing at balancing on this slim tightrope? Broderick said she thinks it’s doing well, adding that “at a large scale, we feel that our cost of goods will be really very achievable.”

The process of manufacturing DNA is actually not that dissimilar to brewing beer, she said, but instead of yeast eating sugar and leaving alcohol, you have E. coli bacteria acting as a mini-factory to make the vaccine. Injecting bits of DNA made by a bacteria into human cells may sound a bit odd, but it isn’t actually a new concept. Making DNA and adding it to cells has long been an important skill for basic scientific research — this is just repurposing existing technology.

With the exception of a special-use waiver in China, no vaccine is currently available to the public. But if you’re interested in sticking out your arm for science, Broderick said you can join the clinical trials. Inovio’s website has a link that will take you to the government’s page, where you can join the waiting list. The vaccine can’t move forward without more testing, and more test subjects.

A clinical trial is a controlled scientific study, so signing up doesn’t guarantee you acceptance. And because half of the participants will get a mock vaccine, even joining the trial does not mean you’ll be truly immunized.

COVID-19 has not affected everyone equally. The elderly are especially at risk, and Black and Latino people, many working in essential jobs during the pandemic, have been getting sick and dying at higher rates.

“If testing [of] the vaccine doesn’t truly reflect the demographics, the population that it’s being designed for, it’s almost a false picture,” said Broderick. Inovio is trying to address this in its trial construction, she said.

“That’s been something that we’ve been very, very conscious of moving forward for our next round of clinical testing, is that those groups are actively encouraged to join the clinical trial.”

Daniel Kulp, a researcher at Wistar who is continuing work on the COVID-19 vaccine, said he thinks many different vaccines are going to be available.

“I think that’s also a benefit too,” Kulp said, “because they’re all going to be slightly different in what kind of immunity they drive and what kind of safety profile they have.”

With so many vaccines racing to go to market, the best-case scenario sees people all around the world having access to several safe options as soon as possible. Not just for Inovio but also for her personally, this is huge, Broderick said.

“As a mum, as a citizen, you can’t help but be moved by the situation that we’re in, that the whole world is in, at the moment,” she said.

Patel, too, sees the importance of the work. “Having a vaccine, ours in addition to other candidates, I think will really help people feel more comfortable and get them back to the normal daily life and being the social human beings that we are.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)