A Delco attorney’s daughter was killed by a distracted driver. Now he’s trying to change how people drive

A Delaware County attorney approaches distracted driving as a matter of respect, and he says scaring teens doesn’t work.

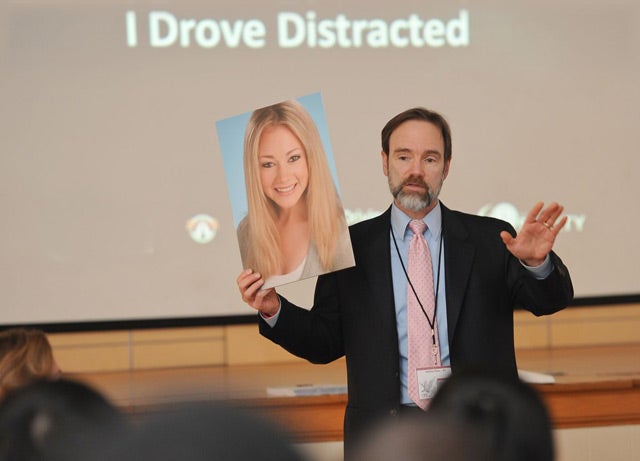

Joel Feldman, an attorney from Delaware County, has traveled the country since 2010, educating adults and students on the dangers of distracted driving in roughly hourlong presentations. His daughter was hit and killed by a driver in 2009. (Courtesy of Joel Feldman)

Delaware County attorney Joel Feldman typically starts his presentations on distracted driving with a confession.

“I used to drive distracted,” he’s heard telling a crowd of adults in a 2016 recording. “I can’t stand up here and tell you that I didn’t, but I’ve changed the way I drive.”

Feldman says scare tactics are unlikely to sway people who habitually text, use Snapchat or Instagram while driving — especially if they’ve avoided an accident up to this point.

“I need to connect with them on a personal level,” said Feldman, describing the admission as a way to garner credibility with students who see adults around them drive with distractions all the time.

Feldman also shares the story of how his 21-year old daughter, Casey, died.

Casey, an aspiring journalist, was working in Ocean City, New Jersey, as a waitress in the summer of 2009.

On July 17, 2009, as she was three-quarters of the way through a crosswalk on her way to work, a driver ran a stop sign at a four-way stop while reaching for his GPS and hit her. Casey died about five hours later.

That same year, her parents founded The Casey Feldman Memorial Foundation and EndDD.org.

“I was deathly afraid that my daughter would be forgotten,” said Feldman. “She didn’t marry, she didn’t have kids, she didn’t have a career, so I wanted do something to remember her.”

Drunken driving and speeding still play a role in most fatal vehicle crashes in Pennsylvania. In 2017, however, distracted driving was a factor in more than 5 percent of the roughly 1,100 deadly traffic accidents and 10 percent of those that resulted in serious injuries, according to the state Department of Transportation.

Delaware State Police say distracted driving played a role in 23 percent of 6,000 reported crashes in 2017, nearly double the number in 2013, according to the DelmarvaNow.

And, in New Jersey, more than 804,000 vehicle crashes were attributed to distracted driving between 2011 and 2015.

Feldman wants to zero out those statistics.

Real-life tragedy resonates

Feldman has traveled the country since 2010, educating adults and students on the dangers of distracted driving in roughly hourlong presentations he made with the help of experts at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Center for Injury Research and Prevention.

The End Distracted Driving website reports the group has reached more than 428,000 teens and adults with the more than 500 speakers it’s amassed.

Feldman describes his approach to discouraging distractions as one promoting respect.

“Just about everyone wants to think of themselves as a person who respects others, respecting others generally includes the golden rule,” said Feldman.

Audience members often say they don’t want to share the road with a distracted driver, Feldman said.

“So maybe we shouldn’t drive distracted either,” he said, adding that it’s not just cell phones. Distractions also include eating, doing your makeup, and adjusting your GPS.

Andrew Kane, who heads the Health and Physical Education Department at Marple Newtown High School in Delaware County, said the school has invited Feldman to speak to students for at least the past five years. Feldman was most recently there last week.

Kane said Casey Feldman’s story resonates with students.

“I don’t think they have a real-life story, and when they see him present as the father, and they see a picture of the daughter — she’s a young lady who looks just like them and acts just like them — they can just relate a little bit different than a teacher or textbook talking to them,” Kane said.

Tuesday he will be speaking at Monsignor Bonner & Archbishop Prendergast Catholic High School in Upper Darby, followed by a stop at the North Montco Technical Career Center.

April is Distracted Driving Awareness Month, meaning Feldman will be busy speaking in Pennsylvania, Colorado, and Kentucky.

He will also give an April 2 talk in Ocean City, where his daughter was killed.

“I can’t bring my daughter back, but I can talk to kids,” said Feldman. “I’m very, very fortunate talking to some wonderful kids across the country, and it’s the young who are going to change how we’re going to drive.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.