A cut above the rest at Kensington Quarters [photos]

Boasting a relationship with local farmers, a connection to the animals and an inspired and educated approach to eating consciously in Philadelphia, Kensington Quarters is bringing butchery to new heights.

Some things in life we never forget — like the first sight of a butchered animal. Its legs bound and hooked at the ankle, hanging from a rafter, skinned and split. A bucket of innards nearby on the floor.

But thanks to packaged sirloin and boneless, skinless chicken, it’s easy to disassociate ourselves from our food, where it comes from, and the work involved before bringing it home in a tidy little package.

Over in Fishtown, the age-old tradition of butchery is alive and well. The crew at Kensington Quarters has renewed the craft, offering an inspired and educated approach to eating consciously and locally, with a retail butcher shop and restaurant on Frankford Avenue.

Co-owners Michael and Jeniphur Pasquarello and Bryan Mayer sought out local farmers. Made deals with a word and a handshake. And embraced a whole-animal philosophy which utilizes every part of the beast, either for the butcher shop or the restaurant, every time.

And it’s a philosophy that extends far beyond the meat locker, to the dairy, eggs and produce. Basically, it comes down to knowing how the animals were raised, what they were fed, and how they were killed.

As food ventures go, this is virtually uncharted territory. Mayer and the Pasquarellos are learning the churn of their own horizontally integrated endeavor and working their way through each delivery of farm-fresh livestock, eggs, and produce. In doing so, they’ve returned the restaurant model to a more traditional workflow, where purveyors are known by their first names — and they’re not Sysco or Silvert.

It’s Henry, actually. Farmer Henry from Lancaster County.

When the trio approached Farmer Henry about buying some eggs, they quickly realized they’d be buying up his whole yield. So they did. They even got to name the farm, Gobbler’s Ridge, which now supplies not only Kensington Quarters, but the 13th Street Kitchens, including Cafe Lift, Bufad, and Prohibition Taproom with farmed eggs.

But it’s not just the eggs. Or the butters from Oasis at Bird in Hand, an organic creamery. Or the grains from Castle Valley Mill, one of the oldest in the nation (all of which are available for retail, in addition to being used on the restaurant menu).

It’s the entire beast. The whole operation. They’re making farm-to-table and nose-to-tail mean something again. It’s a sustainable, conscientious business model. And it’s inspired by an eighth-generation Tuscan butcher named Dario Cecchini.

Mayer had been teaching traditional butchering, slaughtering and farming practices up in the Hudson Valley before hooking up with the Pasquarellos. After a while, though, he wanted to do things differently. So when he made his way to Philly, he brought with him the traditions of an Italian butchering dynasty, introducing age-old techniques to the trendiest of Fishtown businesses.

Cecchini “has a butcher shop and a restaurant. And it just seems like a very natural thing to have,” Mayer explained.

According to Cecchini’s website, “there are four things an animal must have — a good life, a good death, a good butcher and a good cook.”

Mayer, Pasquarello and the rest of the crew are working to engrain that philosophy into every fiber of Kensington Quarters.

Happy pigs are expensive pigs

Whether it’s a chuck roast at the counter or the rare beef at your table, the cost of eating well-treated animals can strain your pocketbook. But that’s not because of the operation size. It’s about the quality, Mayer said.

A quick call to the shop and a couple of prices later and the difference in cost is pronounced. Ground beef is going for $7 a pound, pork chops for $12 a pound (they’re thick cut, about a pound each) and that chuck roast, a popular seller, goes for $10 a pound, weighing in at an average of three pounds.

The animals sold and served at Kensington Quarters roam, range, graze, or forage pesticide-free pastures and woodlots. According to the website, they are free of hormones, antibiotics, steroids, GMO crops and animal by-products.

But can’t consumers get similar products from places such as Wegmans or Whole Foods, which trade in phrases like “free-range” and “humanely produced”?

Mayer thinks not: “Whole Foods and Wegmans deal with pseudoscience, and they’re not really the same product even though they put forth the idea that it is the same product.

“We have a relationship with our farmers that we deal with on a daily basis. Constantly talking about what the animals are doing, what the meat looks like once we start breaking down the carcass. The beef or pork, or sheep.”

So is the meat at Kensington Quarters farmer raised? Pasture raised?

“There really isn’t a term that hasn’t been co-opted by BigAg,” Mayer said. “We call our chickens ‘free roam’ or ‘free run’ because ‘free range’ doesn’t really mean anything anymore.”

They call their beef 100-percent grass-fed. Same thing with the sheep and goats.

“Then when that larger conversation comes, we talk about, yes, they’re on pasture and they’re not sent to feed lots,” he said.

“And our pork are wood-lot animals, so instead of being on pasture, they’re out in the woods where they tend to be a little happier and can be a little more destructive and turn over and root and do the things that pigs do.”

Local livestock, local chef

It’s been about two years since this whole process started for executive chef Damon Menapace.

He’d spent the last year working for Pasquarello at Prohibition and Bufad. Before that he bounded around a bit, spending time in the kitchens of Cochon in Queen Village and the Vetri Company, opening AlaSpina and working at Osteria.

So the kid’s proved his chops around town, but what’s it like to work with livestock at this scale?

“It makes you think about the dish from the whole perspective,” Menapace said. “Instead of picking an ingredient out of mid air … like, I want to use rib-eyes, or want to use veal cheek, you have to sit down and say, what do we have? What’s the flow going to be like?”

First off, the chef and butcher are constantly talking.

“It’s helping them rotate through their stock faster and keeping items in the butcher case at maximum freshness and allows me to repurpose them in other ways,” he said. “I can also still be like, customer No. 1.”

Attention to detail extends throughout the operation. All breads and desserts are made in-house. And all the products in the restaurant are non-GMO, including the wines, which are biodynamic or organic, Pasquarello said.

A couple of dishes to note: The grilled Maitake Mushroom dish, a vegetarian dream served in a puff pastry, with caramelized onion and blue cheese. And the Spelt & Bacon. Not vegetarian, but worthy of a vat-sized fantasy of grains sourced from the oldest mill in the country and veggies and pork, and oozy poached egg.

Don’t sleep on it. The menu changes nearly every day.

Sit down service or grab-and-go

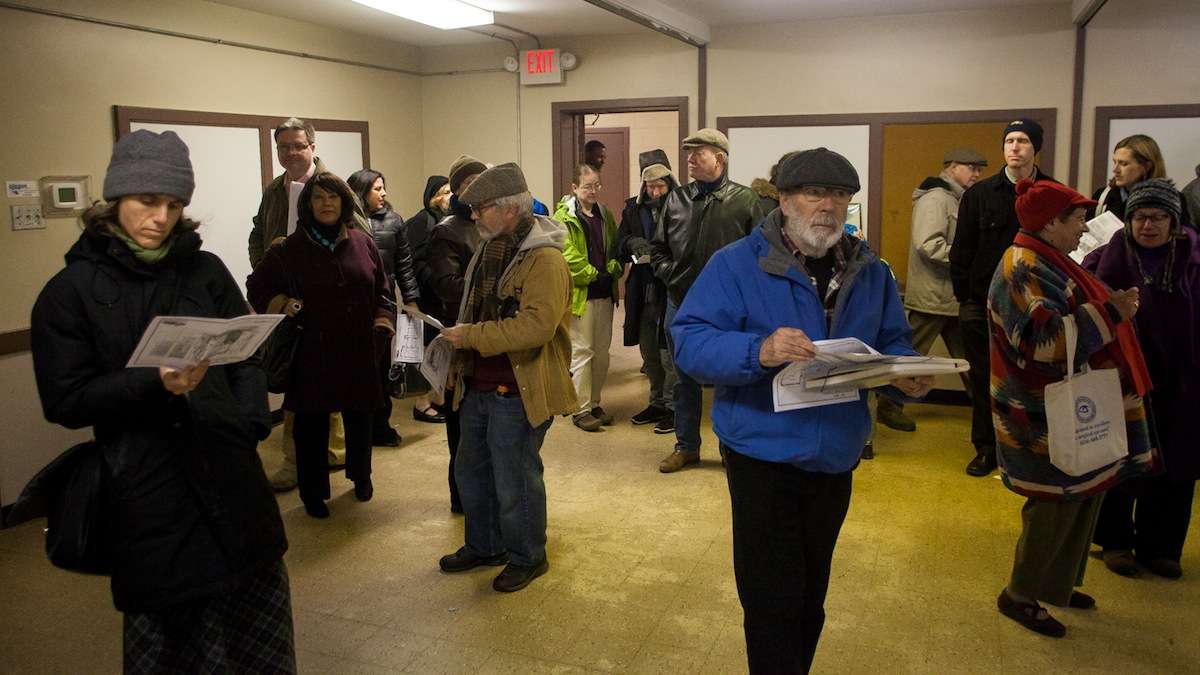

High ceilings, big windows and lots of light balance the industrial buildout with the wood grain, farm-fresh feel at Kensington Quarters.

Positioned center stage, meat cases gleam shiny and clean, displaying only the best of what the area’s farmers have to offer. A wooden butcher block tucked behind the counter allows the butchers easy access to the customers, and the meat-locker, where a week’s worth of animals await their final purpose.

“We like to tell everyone we’re not a steak house, because that’s a concern,” Pasquarello said. “You don’t pick your steak and have it cooked for you. It’s not a steakhouse.”

But you can buy a beautifully trimmed steak to cook at home. Or some breakfast sausages. Or bacon, eggs, ground beef, pastrami, leaf lard … OK, you get the picture.

“The idea was to not have to create all of these added value products out of necessity,” Mayer said. “It should be coming out of want. We do sausages because we want to make them, the charcuterie because we want to do it. Not because we have to move trim or move product.”

The restaurant seats about 100 people, with the butcher shop servicing the kitchen, first and foremost.

Nose to tail. Every animal, every time.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.