Preserving legacy of Frankford

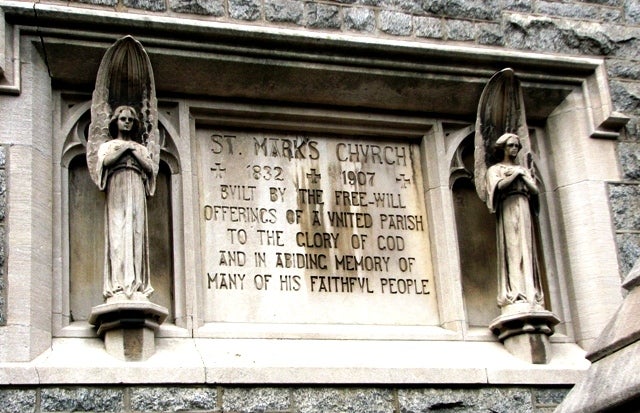

A detail of the 19th century St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, whose congregants have included many of the prominent citizens of Northeast Philadelphia.

June 29

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

The green steel piers and rattling tracks of the El dominate the main route through Frankford, and many of the businesses that line the avenue are struggling or shuttered.

But this thoroughfare was for many years a Lenape trail. In the 17th century, it was a wooded country road, marked as King’s Highway, that William Penn followed to his riverfront manor in Morrisville. Delegates of the Continental Congress trekked over this road in 1775. And during the Revolution, George Washington and his troops traveled “The General’s Highway” on their way to victory in Yorktown.

“Historic Frankford,” the signs on the El’s legs now announce, and the 105-year-old Historical Society of Frankford is working hard to keep it that way. So hard in fact that in May, the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia lauded the achievements of the society’s Center for Northeast Philadelphia History with a special Community Action Award.

The Frankford society’s collaborative meetings with other historical groups from throughout the Northeast section of the city have been “just outstanding,” said Patrick Hauck, director of the Alliance’s Neighborhood Preservation Program. “They are fighting for things most people don’t pay attention to. Their work represents the best kind of grassroots effort.”

But it’s a pitched battle for preservation of the area’s heritage and historic structures.

When Debbie Klak joined the Historical Society of Frankford six years ago, it was a sleepy, closed-door organization without a working phone in the headquarters at 1507 Orthodox St. When the husband of the society’s president became sick, she stepped down and Klak was asked to take over. “I looked at the books here and realized, ‘We’re going to close in our 99th year, and I can’t let that happen.’”

The Historical Society had been founded in 1905 by Thomas Comly Hunter, a native of Bustleton who moved his business to Frankford when it was a thriving center of commerce and transportation. Comly Hunter, William Foulkrod, a Congressman and Frankford attorney who was elected the society’s first president, and other affluent residents interested in the area’s history began collecting artifacts, manuscripts, deeds and other documentation about Frankford, the gateway to Northeast Philadelphia, and records relating to the other small towns, including Tacony, Holmesburg, Bridesburg and Somerton.

In 1930, the Georgian Revival building on Orthodox Street was erected by William Smedley and his brother Franklin, the organization’s second president. The society’s home was designed by architect Frank Rushmore Watson, who built churches up and down the eastern seaboard, including St. Mark’s Episcopal Church on Frankford Avenue, whose congregation included prominent Northeast names such as the Creighton, Welsh and Ashworth families.

But by the turn of the 21st century, the Historical Society building was in need of serious repair. About $133,000 in grants from the city and state supported renovations of the structure in 2007. The grants paid for roof and gutter work, brick pointing, and other repairs to halt moisture penetration, but “we still need hundreds of thousands to address all the issues of the building,” said Jack McCarthy, who oversees project management and the society’s impressive archives.

The annual operating budget of the organization is about $80,000, Klak said, which covers daily operations and the two part-time staffers: McCarthy and an assistant administrator who helps the executive officers. “The funding is hard to get. And the economy has affected how many people come out for fundraisers. So, it’s extremely challenging. Our executive committee has met five times since April” to discuss the society’s financial situation, said, Klak, now vice president of the organization. “We’re going to scale back some things that we see don’t work, and build on other things. With a volunteer organization, it’s very hard. We get a lot of research requests, but we’re revamping the research policy now. We have to think about survival.”

Protection of the society’s headquarters is a priority because of what the building contains. Its museum houses Indian artifacts uncovered in the area, Revolutionary and Civil War swords and rifles, a Colonial pewter collection, 19th-century bucket brigade helmets and axes, and period furnishings, paintings and clothing. The toys include a wood jointed Hessian soldier doll and models of Thomas Castor’s tilting dump wagon and the spiral ladder for a double-decker railway car.

The exhibition space currently displays a donated collection of documents, artifacts and photographs of Abraham Lincoln. An adjacent room is used for programs, lectures, antique appraisals, and meetings.

But the second floor archive and library is the destination for most visitors. The earliest item is a bible published in Germany in 1562 and brought to the Colonies by a family that emigrated to Frankford. Many of the older documents are from the 1680s and belonged to William Penn, including his deeds for land transactions. There is a rich collection of Civil War documents and books, and a set of records of the first savings and loan association in the United States, founded in 1831 in Frankford. “Frankford was a hotbed of the savings and loan industry,” McCarthy explained.

The Historical Society’s photographic collection consists of more than 10,000 images from the mid-1800s though mid-1900s, primarily of landscapes, buildings, street scenes, organizations, church groups, factory workers and families. The archive’s maps date back to the 1700s and reveal the growth and development of the Northeast over hundreds of years.

For local sports fans, there is a complete set of game day programs and photos of the Frankford Yellow Jackets, the first NFL team in Philadelphia and the world champions in 1926.

The library materials are used by people tracing genealogical roots, scholars immersed in studies, and local historians seeking information about the communities of the Northeast.

“There is a constant demand for access, but it’s hard to meet those demands” because of the society’s limited staff and resources, McCarthy said.

Grants have helped pay for the manpower and time to inventory and catalogue the collection. But the archives should be kept in a temperature-controlled environment. “It’s hard for most institutions to renovate the space and maintain that system,” McCarthy said, and the Historical Society doesn’t have the resources for that or for proper storage space.

Beyond the walls of the society’s home, there have been other victories and defeats. “It’s a struggle not only to save our building,” Klak said, but here we are trying to fight fires in the community: don’t tear this down, don’t tear down that!”

The Street administration’s anti-blight campaign razed two 17th-century structures, part of the original Swedish grist mill property near Wohlmrath Park, that had been on the national and city registers of historic places, said Diane Sadler, a board member of the Frankford historical society. A row of 18th century houses on Adams Avenue also were torn down by the city in the 1990s, she said.

All that remains of the Jolly Post, a Frankford Avenue tavern that provided R&R for Gen. Washington, is a commemorative sign high above street level.

Yet historic treasures abound:

• A tiny stone rowhome built in 1726, the oldest structure in the area, blends strangely into the residential landscape on Adams Avenue across from Wohlmrath Park.

• The Waln Street Meeting House, which dates to 1775, is one of the region’s oldest houses of worship.

• The first house to obtain a mortgage in the U.S., in 1826, is the Comly Rich House, 4276 Orchard St.

• The striking pink building at Frankford Avenue and Church Street is the Frankford Presbyterian Church, the third church on the site since the early German settlement. The basement of the first church served as a jail for Hessian soldiers. The cemetery in the back is the resting place of Castor and Decatur family members and Revolutionary War soldiers.

• On the 4600 block of Leiper Street are grand Victorian mansions built for the Greenwood and Blum manufacturing families.

• At Penn and Dyre Streets is the former clubhouse of the Frankford Yellow Jackets, the forerunners of the Philadelphia Eagles.

Most of these buildings are occupied or otherwise in use and in fairly healthy condition. But there are many more sites in need of repair and protection.

Klak has carried the Historical Society’s message to elected officials, but except for one ward leader, “it’s like I mention history and I’m talking another language sometimes.”

The two civic associations that serve Frankford have their plates full with zoning issues and other concerns, Klak said, and the community development corporation does not see neighborhood heritage as a priority.

“When I hear talk about tear-downs and in-fill, with no consideration for historic preservation, it bothers me,” Klak said. “You have to look at our history. Historic preservation and economic development are inextricably connected. You can’t separate them if you want success.”

The Historical Society of Frankford is finding success in collaborative work with like-minded groups. This year’s award from the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia honored the new consortium of local historical groups participating in the Center for Northeast Philadelphia History.

“We brought all these organizations together,” McCarthy explained, “and we meet every other month at different locations in the Northeast to network and share ideas. We’re hoping to raise money together to sustain that.”

The Historical Society of Frankford also plans inaugural induction ceremonies on Oct. 18 at Holy Family University for the Northeast Philadelphia Hall of Fame. The society and university are co-sponsoring the event with the Northeast Times and State Rep. Dennis M. O’Brien, with the goal of raising awareness and appreciation for the deep history of the Northeast and its distinguished residents.

The Preservation Alliance’s Hauck said the Frankford folks are doing all the right things. “The collaborative meetings they are having with other groups is a great model,” he said. “Like many non-profits, it would be terrific to get more money. And when money becomes available, they are the ideal candidate. They are dogged in their determination to keep going. They have drawn in a great range of organizations from a large swath of Philadelphia, and that’s very impressive.”

The Alliance is encouraging the Historical Society of Frankford to identify funding sources that match the projects that they are working on and to get more sites listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places in order to protect them.

“Many resources in the Northeast were being lost for a while,” Hauck said. But the society “can easily become static talking about what was there. The critical piece is to focus on what is remaining,” he said.

The focus of the Preservation Alliance and its Neighborhood Preservation Program is on “getting existing historical societies to talk and figure out what commonalities they have, how to become more activist organizations, and how to be seen as doing something relevant to communities that they still have there.”

Contact the writer at alanjaffe@mac.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.