50 years ago today: A memory of RFK

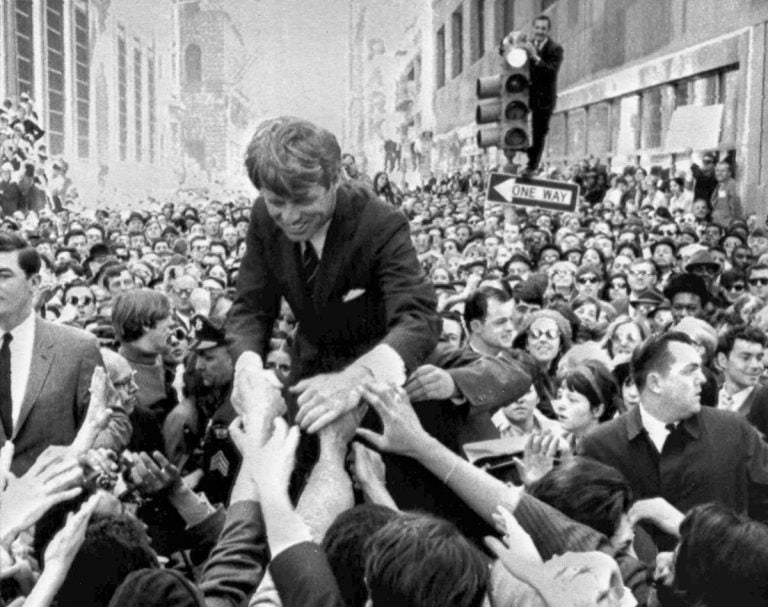

In this April 2, 1968 file photo U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, D-NY, shakes hands with people in a crowd while campaigning for the Democratic party's presidential nomination on a street corner, in Philadelphia. (Warren Winterbottom/AP Photo, File)

Instead of grounding today’s column in the noisome here and now — where the pathetic tinpot patriot is trying to feed the Philadelphia Eagles into his white grievance machine — I want to pluck what Lincoln called the mystic chords of memory.

This particular memory is my own. It’s as vivid as a high-def video. Fifty years ago this morning — June 5, 1968 — I woke up early, eager to drive my mother to the train station. I had just earned my drivers’ license, and, like any newbie, I was thrilled to run any errand for any reason. But before grabbing the keys to the oversized family Pontiac, I told my mother to “hang on” while I checked the 7 a.m. radio news to hear who had won the California Democratic presidential primary.

The announcer began, “Senator Robert F. Kennedy —”

In that instant I said to myself, “His name came first, so he must’ve won.”

The announcer continued, ” — is being operated on at Good Samaritan Hospital — ”

In that instant I said to myself, “Huh? He got sick?”

The announcer finished, ” — for the removal of a bullet in his brain.”

It was tough to be a teen in June ’68, at least for those of us who knew the Vietnam war was bad and believed that politics could be a force for good. I hewed to that belief even though JFK had been assassinated five years earlier while I sat in math class, and even though Martin Luther King had been assassinated two months earlier while I was playing Scrabble with my mother. History is personal and it’s lived in the moment. And now, with the news from Los Angeles, was another such moment.

During the drive to the train station, my mother mistook my silence for standard teen moodiness. All I said was, “I can’t tell you what’s wrong. I’ll put on the news at 7:30.” We weren’t Kennedy acolytes, but it was stirring to see the massive biracial crowds that RFK was attracting on the trail. His nomination prospects were uncertain — Democratic bosses still held sway in ’68, and they didn’t want him — but he was lighting a lantern in the darkness. And when my mother heard the car radio at 7:30, all she said, over and over, was: “I’m sick.” I glumly nodded because that was all I could muster.

RFK lingered that whole day; I monitored the news, eating an entire carton of malted milk balls. A lot of grown-ups simply cried. Like all politicians, Kennedy had his flaws — in June ’68, I knew he had once worked for demagogue Joseph McCarthy, and that as attorney general he had wiretapped King — but at the time of his assassination, he was beginning to craft the kind of coalition that Democrats still need if they are to win in the 21st century.

Kennedy pitched himself to blue-collar whites and minorities. He talked to whites about the systemic injustices suffered by blacks. He told blacks that he was down on welfare (he wanted “to give people a hand up rather than a hand out”) and that he was tough on crime. (He was a rare Democrat who used the term “law and order.” He didn’t want the Republican right to co-opt it, as a dog whistle for racism.)

In the words of RFK scholar Richard Kahlenberg, “Kennedy wooed working-class voters across racial lines with a patriotic populism that blended compassion for the underdog with tough-mindedness about the way the world works. His appeal was a liberalism without elitism, and a populism without racism.”

Any Democrat who hopes to run for president successfully in 2020 will need to reconstitute that appeal. And any Democrat would be well advised to frame the big picture, as RFK did with characteristic eloquence more than a half century ago. We don’t have to wonder how he would’ve viewed Trumpism, because he basically said so during a commencement speech in 1964:

“There are people in every time and every land who want to stop history in its tracks. They fear the future, mistrust the present, and invoke the security of a comfortable past which, in fact, did never existed … Frustrated by change, they condemn the wisdom, the motives, and even the patriotism of those who seek to contend with the realities of the future …

“The answer to these voices cannot simply be reason, for they speak irrationally. The answer cannot come merely from government, no matter how conscientious or judicious. The answer must come from within the American democracy. It must come from an informed national consensus which can recognize futile fervor and simple solutions for what they are — and reject them quickly.”

When RFK lay mortally wounded on that hotel kitchen floor, his last words were “Is everybody OK?” The answer, 50 years later, is: No, we are not. But his words still give us hope.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.