Building for transit-based living

Lumber Yard Condos in Collingswood, NJ.

March 17

By Seth Budick

For PlanPhilly

If you are a resident of Philadelphia, you can be forgiven if the term transit-oriented development (TOD) does not easily roll off your tongue. In much of the country, however, TOD is a buzzword among planners, developers, and smart growth advocates.

As its name suggests, TOD is a form of development that rejects sprawl in favor of concentrating population and job growth around transit stations. Current conditions in the US, including the construction of new transit infrastructure, increasing traffic congestion and gas prices, as well as demographic shifts towards smaller, more urban households, seem to provide fertile ground for TOD.

Philadelphia, with its extensive existing transportation network and dense concentration of jobs and population, might appear to be an ideal environment for TOD, but implementing it here would require overcoming substantial obstacles.

What is TOD?

Despite the novelty of its name, TOD describes what was largely the default pattern of urban and even suburban development prior to the rise of the automobile. That is, a dense clustering of homes and businesses around transit stations. Local examples include the older sections of towns along the main line, which according to Karin Morris, Manager of the Office of Smart Growth at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC), can all be considered TOD. Development along transit corridors, like the streetcar suburbs of West Philadelphia, would also qualify.

TOD has recently gained attention for its application in suburban settings – places where zoning codes have long enforced a separation of uses, and where transportation has been dominated by the automobile for most of the 20th century.

TOD describes a general approach to development, and as such, the specifics of its implementation can be quite varied. Nevertheless, there is substantial consensus that in order to qualify as TOD, development should be characterized by a series of fairly well defined principles. The Center for Transit-Oriented Development, a think tank for promoting best practices in TOD, and a program of the nonprofit group Reconnecting America, which focuses on integrating transit systems with the communities they serve, has been particularly active in establishing such guidelines.

Central to its conception of TOD is the principle of “location efficiency.” Location efficient development makes maximal use of its proximity to transit, as well as its diverse range of shops and services, to reduce the number of automobile trips that its users must make. Ideally, not only will those living or working near a station be more likely to ride transit between job and residence, but the mixture of uses within a TOD should reduce the number of car trips they need to make in order to shop, drop their children off at daycare, or complete other routine tasks. If nearby transit stations are also surrounded by clusters of shops and services, residents could meet even more of their needs with just a short transit ride.

TOD’s benefits, at least theoretically, are legion. They include: providing an alternative to driving (and its accompanying environmental impact), a reduction in household transportation costs, less need for parking lots, increased transit ridership (and farebox recovery for transit agencies), curbing inefficient development of greenfields (previously undeveloped and agricultural lands) and preserving open space, fostering economic development, and, potentially, creating pedestrian-friendly towns and neighborhoods with their own unique identities rather than generic and anonymous sprawl.

Current TOD Development and Best Practices

Transit-oriented development has increased in recent years, spurred, in large part, by the construction of new transit lines in cities across the country. Transit ridership has been growing nationally as rail-based transit systems have been built or expanded in virtually every major city in the country. Even places such as Houston, Minneapolis and Charlotte, which largely abandoned their rail transit infrastructure when cars became popular, have made major new investments.

In many of these cities, transit development has been explicitly linked with changing land use patterns, concentrating development and reducing sprawl. In many cases, this has involved the construction of new TOD in relatively suburban locations around stations on new light rail lines (similar to SEPTA’s trolley lines, but generally running separated from traffic in exclusive rights-of-way). This has often required rezoning the areas around transit stations in order to accommodate greater densities and a mixture of uses.

Transit agencies have frequently played extremely active roles in fostering TOD, though that precise role varies with the agency’s enabling legislation. These activities have included developing station area plans, identifying and ranking stations that are prime targets for TOD, conducting market analyses for development around specific stations, and seeking out developers.

Many transit agencies, including Washington D.C.’s WMATA, are able to purchase, sell, and lease land for development purposes, with the resulting revenues, which may be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, constituting a potentially significant fraction of their budgets. Often, this “joint development” role of the transit agency is seen as integral to its mission and, in the case of the WMATA, is set out explicitly in its Joint Development Policies and Guidelines:

WMATA defines joint development as a creative program through which property interests owned and/or controlled by WMATA are marketed to office, retail/commercial, recreational/entertainment and residential developers with the objective of developing transit-oriented development projects. Projects are encouraged that integrate WMATA’s transit facilities, reduce automobile dependency, increase pedestrian/bicycle originated transit trips, foster safe station areas, enhance surrounding area connections to transit stations, provide mixed-use including housing and the opportunity to obtain goods and services near transit stations, offer active public spaces, promote and enhance ridership, generate long-term revenues for WMATA, and encourage revitalization and sound growth in the communities that WMATA serves.

In Philadelphia, by contrast, SEPTA is only permitted to acquire land in order to provide transportation services (which includes stations and parking), according to David Fogel, SEPTA’s Director of Long Range Planning. “We’re not a redevelopment authority. We can purchase property if it has a transportation purpose,” he said. Unlike the transit agencies in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, “SEPTA is prohibited from creating a land bank around transit stations for non-transportation purposes in order to solicit TOD proposals,” Fogel said.

As a result, SEPTA has had limited involvement in TOD around its stations. But that may change thanks to a 2004 state law allowing the creation of Transit Revitalization Investment Districts. The law provides grant money for municipalities and counties to work together with their local transit agencies to conduct planning studies for the areas around transit stations (TRIDs). It also allows a portion of the increased tax revenues generated within the TRID to be used for local improvements and maintenance. Finally, the law may grant transit authorities permission to take a more direct role in joint development. See sidebar.

While transit-oriented development is increasing in popularity and appeal, making it happen is not always easy. This is evident in the comments of practitioners who reflected on TOD projects across the country for The New Transit Town: Best Practices in Transit-Oriented Development – a recently published book edited by Hank Dittmar and Gloria Ohland. One consistent theme that emerges from their writing is the need for an overall vision for planning and implementing TOD, accompanied by strong leadership.

With multiple stakeholders whose interests are not necessarily aligned, it appears to be imperative that a single entity, usually the local government, guides the long-term vision and streamlines the development process. Dittmar, Ohland, and their contributing authors stress that it is extremely important to developers that local governments create clear planning guidelines – and then implement regulations that favor developments which follow those guidelines.

The development process must be made as predictable as possible to offset the complexities of developing TOD, which include the risks posed by land acquisition, rezoning, lengthy regulatory reviews, variance applications, and community opposition.

To spur TOD, local government is also frequently called on to help fund infrastructure investments such as utilities and streetscape improvements, and to offer direct incentives for developers, such as allowing them to build residential units at greater densities than those previously permitted. In fact, except in extremely strong markets, these sorts of incentives have generally been necessary to make TOD projects go forward, according to the contributors to The New Transit Town.

Public subsidies for development can take the form of tax credits, funding from municipal redevelopment authorities, or assistance from a wide variety of other state or federal sources. One common source of funds is tax incremented financing. In this model, a fraction of the increased property tax revenues that result from the appreciation of property values adjacent to new development are funneled back into paying for TOD related capital expenses and maintenance.

Prospects for TOD in Philadelphia

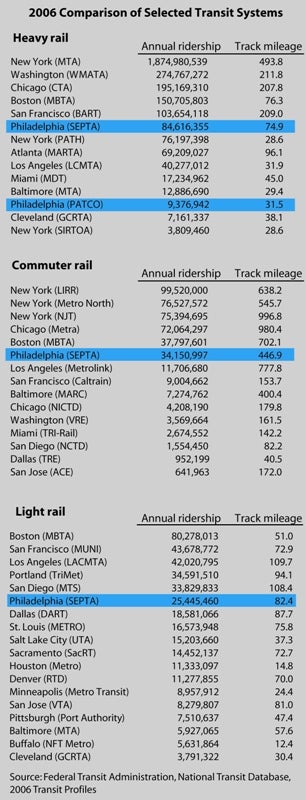

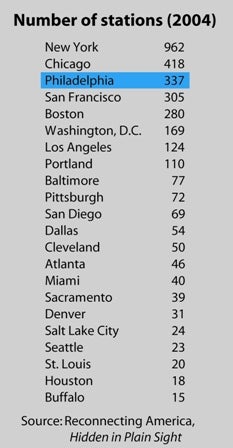

Though Philadelphia has shed a large portion of its rail infrastructure – old trolley maps show hundreds of miles of tracks that no longer exist – it has kept many of the most valuable pieces. For instance, while the city once had trolley lines running North-South through Center City on almost every numbered street from 2nd to 23rd, it has retained much of its high capacity, high speed infrastructure, including the Market Frankford Line (MFL), Broad Street Line (BSL) and Subway Surface Lines. The Broad Street Line in particular, with its four track arrangement allowing for express trains north of Walnut Street, represents an asset otherwise largely unique to New York City. Indeed, the transit networks that are being built across the country, at a cost of hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars, will fall far short of SEPTA’s extensive reach and capacity. Based on its sheer number of rail stations, SEPTA ranks third in the nation, and its ridership has remained relatively strong, though not terribly impressive compared to several of the other largest transit agencies in the country.

But in contrast to the high density development that should ideally characterize TOD, many of Philadelphia’s transit stations are surrounded by land that is remarkably poorly used. The long reconstruction of the Market Street Elevated structure in West Philadelphia has had a profound impact on businesses along that corridor with long stretches of commercial storefronts either vacant or in disrepair. Large tracts of vacant land abut the street and in several cases, new commercial development, including two new supermarkets, though constituting important neighborhood assets, are surrounded by large surface lots and are either set well back from the street or turn a blank wall towards it.

Similar patterns of highly non-transit supportive land use characterize many stations along the Broad Street Line where, at the Girard Station for instance, two out of four corners host drive-thru fast food outlets or gas stations. A conspicuous exception occurs at the Cecil B. Moore station, near Temple University, where large retail and residential developments, as well as the Liacouras Center, the University’s basketball arena, are situated immediately adjacent to a subway station. Even there, however, a large University parking lot occupies one prime corner of the intersection immediately adjacent to the subway entrance. Development at stations along this line is “a no brainer” according to urban planner John Beckman, Principal at Wallace Roberts & Todd and one of the authors of a TOD plan for the Market Frankford line.

This generally poor land use is certainly related, in part, to the lack of value attached to close proximity to transit in Philadelphia. In a report on the opportunities for TOD in Philadelphia that he prepared for Neighborhoods Now, Richard Voith, Senior Vice President and Principal of Econsult Corporation, and former member of the SEPTA Board of Directors, argued that the value of transit derives, in large part, from the long-term certainty of its service, the number and desirability of its destinations, the frequency of its service and its integration with other services.

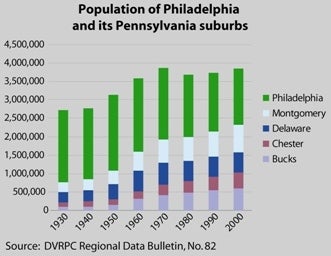

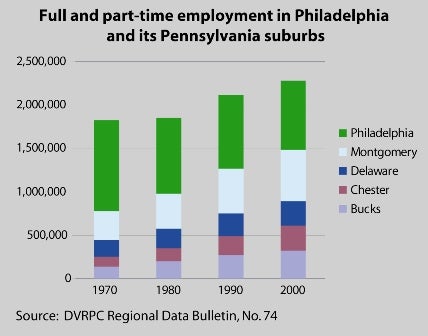

With last year’s creation of the Public Transportation Trust Fund, which combines funds from state sales taxes, Turnpike Commission Fees, lottery money and other sources for state-wide distribution, SEPTA’s financial position is much improved, going a long way towards assuring riders of the long-term availability of service. A more difficult problem is the steady migration of population and jobs out of Philadelphia and into its low density suburbs, which reduces SEPTA’s ability to serve the destinations required by residents of the region.

Though the city of Philadelphia still has an extremely dense concentration of both jobs and population, the numbers of both have been declining for decades, while the region overall has continued to grow. Serving these increasingly dispersed customers and employment centers is extremely costly and inefficient for a transit agency, further stretching its resources and hindering its ability to provide high quality service on existing routes.

Decentralization of growth need not have such strongly negative consequences if that growth is concentrated around transit stations, however. “Reverse commuting is a huge benefit to a transit agency, for ridership efficiency” argues Sam Zimmerman-Bergman, Project Director at Reconnecting America. But according to Zimmerman-Bergman, making TOD a relevant force in reshaping the city will require a regional conversation about the direction of growth. “As jobs have decentralized, I think there’s a risk that transit becomes less valuable. Regionally, making sure that jobs are locating near transit, so that transit remains relevant, is really important.”

Even if these trends can be reversed or minimized, the existing relatively weak housing and job markets in Philadelphia pose a key question for TOD: is there demand for housing and other development in the neighborhoods that are well served by transit? New TOD has tended to be concentrated in cities with strong employment and real estate markets. According to Zimmerman-Bergman, “In a place like L.A., a place that’s growing and where there’s demand for housing, I think it’s a little easier to get TOD off the ground because there’s just more demand for development and so it’s a little easier for the development community to go in and pay some of the higher land costs that often exist around transit and to make some of the infrastructure upgrades that need to happen to make a project feasible.”

That is not to say that TOD is impossible in weak-market cities like Philadelphia. After all, according to Zimmerman-Bergman, those regions are still growing. “When there’s growth in the region, there is still some demand for housing, or for development, it’s just been leaking out to the suburbs and a lot of the underlying demographic shifts in this country are shifting people more towards urban living.” Together with the increasing cost of the suburban lifestyle, Zimmerman-Bergman suggests that these factors are driving demand back towards cities and refocusing growth around transit with a premium placed on accessibility.

Beverly Coleman, Executive Director for NeighborhoodsNow, a Philadelphia non-profit dedicated to improving the health and competitiveness of low and moderate-income neighborhoods, also believes that the prospects for TOD in Philadelphia are strong and that they may hinge on the city’s ability to promote growth and to direct attention to the value of its transit system. “I do think that under the new administration, the city is probably going to be more aggressive about attracting people. I think that that whole SEPTA system is just a huge asset that we haven’t leveraged and I think public transit is going to be more important in the future.”

Others, including John Beckman of Wallace Roberts & Todd, agree that whether TOD happens in Philadelphia is largely a question of prioritization by the city. “I think the big issue really is whether the city thinks that there’s sufficient market potential here to make a major investment in public resources, by which I mean staff, time, political capital in terms of zoning changes, which is always difficult, and then perhaps even dollars in terms of infrastructure improvements.”

There does appear to be a good deal of optimism that the change in administration presents an important opportunity for getting TOD off the ground in Philadelphia. Rina Cutler, the city’s new Deputy Mayor for Transportation and Utilities, is certainly aware of the potential benefits. “Philosophically, anytime that we can have transit in a dense city environment, that can only be helpful.” According to Ms. Cutler, ”Anytime you have people who do not have to get in their cars, either for quick trips that are 10 minutes away, or add to the commuter problem in terms of congestion, then that can only be a good thing.” Though she is still learning the details about the potential for TOD in Philadelphia, she added that she is “certainly more than willing to spend some time and look at the subject.”

One approach to gaining early momentum for TOD in Philadelphia is to promote development, initially, around those stations that offer the greatest potential for success. Though he considers every station along the MFL and BSL to be a candidate for TOD, Richard Voith advocates starting with a few stations that could become local, and highly visible, examples of successful TOD. One of the biggest problems with constructing TOD in novel environments has been overcoming the apprehension of stakeholders about the viability and need for a new and unfamiliar form of development; concerns that could be assuaged by pointing to successful local developments.

Karin Morris at DVRPC similarly suggests that developing a list of high priority sites would be a useful first step towards engaging developer interest in TOD in Philadelphia. “It would be great if the city came out with a statement that said, ‘here are the top 10 sites for TOD and why.’ If they could rank them based on where the most destinations are, where the density is, where the service is best, even though it’s a weak market, you have all these other factors that could complete the picture.”

A central question for TOD in Philadelphia is the form of public subsidies that might be necessary to spur developer interest. Beverly Coleman at NeighborhoodsNow is in the thick of this discussion as her group is currently working on TOD plans for two SEPTA stations in Philadelphia. According to Ms. Coleman, it is still too early to say what kinds of incentives will be necessary, but for the sort of mixed-income housing that they would like to see “you’re looking at something like funding from low income housing tax credits.” She added, “I think the real issue is what are the economics of doing real estate development in those communities and how do you incentivize it?”

The scale of any development will certainly be impacted by those economics. For instance, according to Sam Zimmerman-Bergman of Reconnecting America, Philadelphia’s standard row-house density is perfectly transit supportive, but in order to be economically viable, new TOD is likely to require greater density. “If you’ve got vacant land right at a transit station, keeping it to three stories is probably going to make development unfeasible.”

Another key issue that currently confronts TOD in Philadelphia is the city’s zoning code. While not necessarily impeding TOD, such development “is not made easier by current zoning, because it’s the classic laundry list of commercial zones, retail zones, residential zones” according to John Beckman of Wallace Roberts & Todd. “None of the existing ones really bring all the pieces together and deal with high density, mixed use, and shared parking.”

In municipalities across the country, TOD has often been accommodated by substantial adjustments to the zoning code. In many cases, this has involved the creation of new TOD zoning districts that permit mixed uses and allow much higher densities than in surrounding areas.

In 2007, city voters approved the creation of a Zoning Code Commission to oversee the reform of that code. How the new zoning code will treat TOD, and whether it will acknowledge the unique potential of development near transit stations, is an open question. As Bill Kramer, acting division director of the Development Planning Division of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission Kramer put it, “I don’t know what the future holds for the Zoning Code Commission, or for its efforts. That having been said, I do think that these [zoning code changes] are, going to go forward because they basically need to. I know that there’s interest, on behalf of different council people, and to that end they would like to see something go forward, and therefore something more than likely will go forward.” Relatedly, NeighborhoodsNow has received funding from the DVRPC that is allowing them to work with the city to develop a new TOD neighborhood zoning classification. The request for proposals has just gone out, Coleman said.

Municipalities interested in fostering TOD have also commonly implemented design standards regulating specific characteristics of the development. In The New Transit Town, Ellen Greenberg, Director of Policy and Research for the Congress for New Urbanism, enumerates a variety of the elements that are frequently the subject of such controls: the location of uses (such as requiring retail on the ground floor), sidewalk design (such as accommodation for street furniture), building setbacks, the location of pedestrian entrances to buildings, the percentage of windows on the first floor, and, importantly, the provision of parking.

Parking is a huge issue. As Julia Parzen and Abby Jo Sigal point out in The New Transit Town, parking issues provide a good illustration of the complexities of creating TOD.

TOD advocates say fewer parking spaces are needed for this kind of development. Residents of these projects make fewer trips by car, they say. And parking can be shared between complimentary uses – for example, residents could share the spaces where they typically park overnight with commercial tenants, who could use them during business hours. In TOD projects, parking spaces might be sold or leased separately from residential units or commercial buildings, so tenants and residents may choose not to purchase parking. This, too, reduces the need for parking space, proponents say.

As the former Executive Director of the Philadelphia Parking Authority, Rina Cutler, Philadelphia’s new deputy mayor for transportation and utilities, has a background in parking. Having only occupied her position since March 3rd, Cutler is still familiarizing herself with the TOD possibilities in Philadelphia. But if TOD comes here, reduced parking would make sense, she said. “Parking standards for normal developments are not likely to work for TOD. You would want less parking, and you would need less parking.”

Since many zoning codes around the country currently call for parking minimums rather than maximums, the idea of reducing the parking supply comes as a surprisingly novel one, and is not universally loved. The concept makes some banks that finance private development apprehensive, because they fear a smaller number of parking spots will deter potential tenants. And even the transit agency will also want assurance that there is enough parking for riders who drive to the station.

In Philadelphia, parking requirements vary widely, although, in general, the rule of one space per residential unit applies, according to Kramer. As he puts it, “currently, the code requirements for parking are a little less than clear. It’s all the kind of thing that where you are is going to determine how much parking is required in that particular district.”

Currently there is flexibility, in the form of variances, for developers to reduce the parking that they provide. According to Kramer, “If you have someone who walks into the office and says, ‘here’s what I want to do, and this is how I’m going to deal with it. I’m creating accessibility to transit stations,’ we would be very inclined to support the grant of such a variance.” In the end though, the granting of such variances is up to the Zoning Board of Adjustment “and therefore, the zoning board would be the final arbiter on that because like it or not, that’s how it’s all set up.”

Across the River

While SEPTA’s role in promoting TOD has been limited thus far, New Jersey Transit has been actively pursuing TOD, said Morris of the DVRPC. New Jersey has created an Office of Smart Growth and has a state plan that coordinates local planning in areas such as land use and transportation; a guiding document that Pennsylvania lacks. New Jersey Transit also has staff dedicated to assisting communities generate “transit-friendly vision plans” for their stations and the New Jersey Department of Transportation has a Transit Village Initiative that is “designating towns as transit villages based on very specific criteria that allows them to get priority funding,” according to Ms. Morris.

Located approximately half a mile from the PATCO station in Collingswood, New Jersey, the LumberYards Condominiums are one of the few recent examples of TOD that have been implemented in the region, according to Ms. Morris. On a recent day, however, while cars streamed in and out of the garage, two out of the three residents leaving the building on foot said that they rarely if ever ride PATCO.

Chris Monti, whose fiancé lives at LumberYards, said, “We use it to go into Philly 2-3 times a year, but we usually drive.” Asked about riding PATCO, Jared Alexander, another resident, said, “I haven’t used it yet, but I plan to.” At least some residents are enthusiastic about the access to transit though, including retiree and former Center City resident Bill Quay. Though he only moved in within the last few months, Mr. Quay already rides PATCO three times a week to get to Philadelphia and estimates that living near transit has cut his driving in half. Asked whether the station’s proximity impacted his decision to live at LumberYards, Mr. Quay’s response was unambiguous. “Absolutely,” he said. “It’s easy to hop on the train and 13 minutes later you’re there.”

Current TOD in Philadelphia

SEPTA, together with local municipalities, consultants and non-profits, is currently engaged in TRID planning studies at six of its stations. Four of these are in the Pennsylvania suburbs at Croydon, Marcus Hook, Ambler and Bryn Mawr Stations, and two are in Philadelphia at the 46th and Market Street station of the MFL and at the Temple University Regional Rail station, a station served by all seven rail lines.

The TRID planning at both 46th Street and Temple is being managed by NeighborhoodsNow, which worked with the city to secure funding from the Department of Community and Economic Development. NeighborhoodsNow has selected Interface Studios to conduct the planning process, which Coleman expects to be completed by June 2008. In addition to the standard elements of a planning study, a specific goal of this work, will be to determine whether “the current legislation provides sufficient incentives to be able to do real estate development in low wealth neighborhoods,” Coleman said. And she expects that additional analysis by Econsult should help in answering that question. As well as its immediate implications for the two neighborhoods, she hopes that the TRID planning will allow them “to share the lessons we learn from the planning process, and just elevate the visibility of TOD, especially neighborhood TOD, in Philadelphia.”

Coleman said these two sites were chosen largely because of the ongoing interest of two Community Development Corporations (CDCs): the Enterprise Center CDC at 46th Street, and Asociacion de Puertorriquenos en Marcha at the Temple University station. In both cases, the CDCs would like to do mixed-use projects and are “in the early feasibility stages for their projects,” with the land acquisition process still underway. SEPTA has been helpful in the planning process thus far, said Ms. Coleman, participating in the advisory committee and being engaged and receptive to ideas.

With national conditions for TOD resembling a perfect storm, local advocates are hopeful that Philadelphia may also be able to capitalize on a confluence of factors to promote new growth around transit.

“I just think we have this enormous opportunity,” Coleman said. “You’ve got a new mayor and new leadership at SEPTA, you have SEPTA in a much better position financially, and you have a city that’s saying ‘we want to make the process for doing real estate development easier with the zoning code,’ so I think we have a real opportunity to get this right.”

Contact the reporter at sbudick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.