From our Reprise Collection: Making the Center City commuter connection

Editor’s note: With the Center City Commuter Connection turning 30 tomorrow, PlanPhilly thought it would be appropriate to look back at a seminal piece of explanatory journalism that examined what it took to make this hugely important link in Philadelphia’s transportation infrastructure. The article was the work of PlanPhilly contributor Steve Ujifusa.

At the opening ceremony of the Center City Commuter Connection, SEPTA chairman Lewis F. Gould remarked: “What we have accomplished here has never done before in the United States. We have, in one regional rail system, joined suburb to suburb and suburb to city.” (i)

The Center City Commuter Connection, a direct rail link between Suburban Station and the new Market East Station formally opened for business on Nov. 12, 1984 after six years of construction. The project, which included a four-track wide tunnel and a new underground Market East Station, was finished on time, within its original budget, and with no worker fatalities. It linked all 198 commuter stations and united 500 miles of track in the Philadelphia region into a single system. It was also the largest federally funded mass transit project to date, costing $330 million. (ii)

This public project achieved what never could be done when the railroads were under private ownership. From the 1880s to the 1960s, Philadelphia was a two-railroad town. The first was the mighty Pennsylvania, headquartered at the Broad Street Suburban Station near City Hall. Along with its national network of railroads, it had also helped develop upscale suburban towns along its “Main Line,” today know as the R5 Line.

It also developed the “in-town” suburbs of Germantown, Mount Airy, and Chestnut Hill West in the northwest section of the city — today’s R8 Line. The Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, occupying its great Renaissance-revival terminal at 12th and Market Streets, had also developed commuter communities north of the city in Bucks and Montgomery Counties, such as Warminster, Ambler, and Doylestown. It also served a set of stations running parallel to the Pennsylvania’s Chestnut Hill branch, such as Wyndmoor and Gravers Lane — today’s R7 Line. The Reading’s above-ground viaduct, which cut through a largely industrial part of the city, emerged at Brown Street and then paralleled Broad Street before branching out into separate lines.

Until the completion of the Center City Commuter Connection, the two trunk lines did not connect. A passenger who wanted to go from, say, Paoli to Doylestown had to walk several blocks from Suburban Station to the Reading Terminal. The distance was more than an inconvenience during inclement weather; city planners felt the lack of a connection between the two stations was severely hampering Philadelphia’s role as a regional commercial center.

Ultimately the project’s backers hoped that the new Center City Commuter Connection would foster economic development in the city of Philadelphia and its surrounding suburbs. By the 1970s, the exodus of business, industry, and residents to the suburbs had bled the city dry. Numerous attempts had been made to draw affluent residents back into town, most notably the through the redevelopment of Society Hill. But bringing back historic neighborhoods was not enough; the hope was that a massive infrastructure improvement would channel people and tax revenue back into the city’s deteriorating commercial core.

Figure 1. Broad Street Station and trainshed before the 1923 fire. Courtesy of PhillyHistory.org.

Figure 2. Reading Terminal. Courtesy of PhillyHistory.org

The Planning Process

The construction of the Center City Commuter Connection was brought about by the financial woes of the Pennsylvania and Philadelphia & Reading railroads and the consolidation of their commuter lines under the power of a regional transportation authority. Following World War II, the Reading and Pennsylvania started to crumble in the face of automobile competition, and both lost interest in their money-losing commuter lines.

In 1963, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, or SEPTA, took over the operations of both commuter systems. But even after cutting their passenger service, both railroads continued to hemorrhage cash. In 1968, the faltering Pennsylvania merged with its archrival, the New York Central. It was too late. The new Penn Central combine filed for bankruptcy only two years after its formation, and by 1976 the private company completely collapsed. That same year, the Reading Railroad also disintegrated. Following the collapse of Penn Central, the new entity, Conrail, charged SEPTA fees to use their tracks. Congressional legislation stipulated that Conrail had to be out of the passenger service business by 1983, after which SEPTA would take over direct operation of the commuter system. (iii)

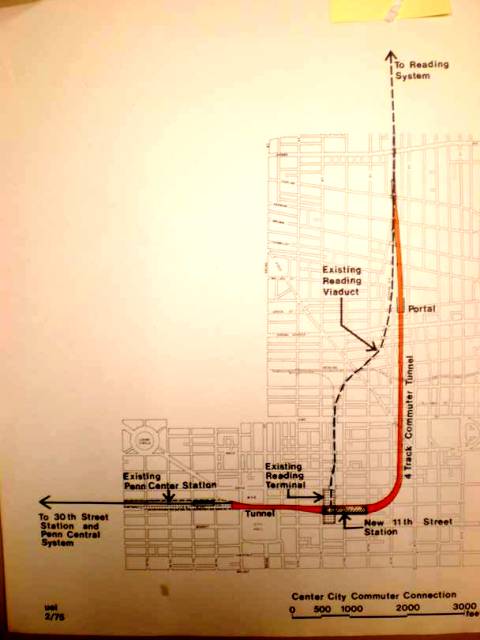

Soon after the suburban commuter rails were placed under public control, the City of Philadelphia began to think of ways to link the two commuter railroad systems. The City Planning Commission proposed a project called the Center City Commuter Connection. The grand scheme would provide a 1.8-mile long rail link between Suburban Station and the new Market East Station, a link that would lie beneath the Reading Terminal train shed and meet the old Pennsylvania tracks at grade. (iv) The tunnels would contain four standard gauge tracks that could handle 80 trains per hour. (v)

As laid out by the City Planning Commission, the Center City Commuter Connection would consist of two components. The first would be the construction of a new Market East station. The second would be the digging of a new railroad tunnel under Filbert Street connecting Market East and Suburban Stations. The old Reading rail line would be buried until it reached Spring Garden Street, where it would emerge from a new portal. The result would be that a passenger could ride nonstop from a former Reading commuter station such as Doylestown or Ambler all the way to a former Pennsylvania station such as Villanova or Swarthmore.

The scope was daring at the time. Philadelphia, like many major cities, was in fiscal crisis. The flow of businesses and residents from the city that had begun in the 1950s had turned into an exodus. Center City’s office buildings, built largely before World War II, were becoming under utilized. Worse, the flow of federal grants that had funded billions of dollars worth of urban infrastructure improvements in the years following World War II was slowing to a trickle. Edmund Bacon, the powerful head of the City Planning Commission who had raised the idea of the Commuter Connection back in 1947, had retired. Three years before Philadelphia made its request, President Ford had refused to help bail out New York City from bankruptcy. On October 30, 1975, the front page of the New York Daily News screamed the headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” (vi)

In addition, the Philadelphia project’s promoters encountered considerable resistance from local labor leaders, which contributed to the initial lack of federal interest. According to the New York Times, “the city lost out because it failed to come up with an adequate agreement that would protect the rights of the labor unions affected by the project.” (vii) In addition, local business owners voiced concerns about pedestrian traffic disruptions, and some property owners opposed the condemnation of their properties. In a January 17, 2008 interview, project engineer Michael Griffin stated that some sued the city on the basis on inverse condemnation, claiming that the disruption caused by the construction project was no different than government seizure, and demanded “exorbitant” compensation. (viii)

Figure 3. Map Showing Proposed Center City Commuter Connection, including new Market East Station and burying of part of the Reading Viaduct.

From the Project Engineer’s Report. Courtesy of Ruben David, P.E.

Yet the city continued to push for federal funding, arguing that the Commuter Connection would greatly enhance operational efficiency and create a tremendous number of jobs in the construction industry. (ix)

Dr. Bruce F. Baldwin, chairman of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, argued in the project’s defense that, “With the tunnel, the network could haul more than 90,000 during peak hours and relieve pressure on our streets and highways.” (x) The Commission then issued a report arguing that a unified rail system would not only be more convenient for existing commuters, but that it would also bolster job growth in Center City. “Construction of the center city commuter connection,” the report stated, “would be the single most effective means of improving public transportation capacities in Philadelphia.” (xi) In addition, the study urged that the linking of the two commuter systems would spur job creation within a city that was rapidly losing white collar jobs to Montgomery County and South Jersey and manufacturing jobs overseas. The study claimed that the Center City Commuter Connection would help boost Center City jobs to 445,000, and increase its permanent population by 7,200. (xii)

The Legacy of Broad Street Station and the Chinese Wall

Broad Street Station, built in 1882 and enlarged ten years later by the famed firm of Furness & Evans, was a brick palace bristling with turrets and spires and crowned with a soaring clock tower. It was located at the heart of the city’s business center and made commuting much more convenient for the city’s office workers. Before the station’s construction, trains terminated at 30th Street Station on the west side of the Schuylkill River, a long way from city center. To connect their new station to its main line, the Pennsylvania built a stone viaduct that linked it with 30th Street Station. Because steam trains could not operate in tunnels, the railroad had no choice but to build their new spur above ground.

If the station was an architectural masterpiece, the viaduct was a monstrosity. Generations of Philadelphian’s had scornfully called it the “Chinese Wall,” because it created a virtually impenetrable barrier between City Hall and the Schuylkill River.

Sixteen tracks wide at its widest point and several stories high, the viaduct straddled the blocks between Market Street and Pennsylvania Boulevard (modern-day John F. Kennedy Boulevard). Passing locomotives spewed soot and cinders onto the streets below. The noise and pollution depressed surrounding real estate prices. To pass under the viaduct, one had to walk through one of a series of dank, filthy archways that constantly shook from the passing trains above. Few people wanted a crossing under the wall as part of their daily routine.

The “Chinese Wall” was not just a physical barrier; it was also a social one. It created two Philadelphias: “North of Market” and “South of Market” (xiii) by amputating Philadelphia’s business and fashionable residential districts from the rest of the city. Among a certain set of Philadelphians, a residential or business address south of Market Street connoted respectability and legitimacy. An address “north-of-Market” as the phrase went hinted at something socially or economically suspect. (xiv) For seven decades, the “Chinese Wall” caused blight and decay that foreshadowed the effects caused by cross-city interstates such as I-95.

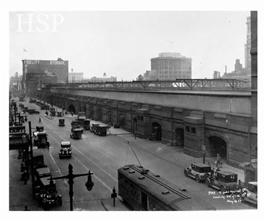

Figure 4. The “Chinese Wall” at street level.

Courtesy of PhillyBlog.com

Figure 5. The “Chinese wall” as viewed from the top of Broad Street Station, looking west towards 30th Street Station, c. 1945.

Courtesy of PhillyBlog.com.

By 1900, advances in technology had allowed New York to overcome its own version of the “Chinese Wall.” During the second half the nineteenth century, Park Avenue north of 42nd Street served as the city’s main railroad artery, bringing commuter and long-distance steam trains into Grand Central Station. The dirt and noise made upper Park Avenue the most undesirable street in Manhattan. It was lined with slaughterhouses, factories, and run-down tenements. After a number of gruesome accidents between street cars and onrushing trains, the city ordered the Vanderbilts to cover up and electrify the Park Avenue tracks leading to Grand Central Station. When the project — which included a new terminal — was completed in 1913, it was a win-win situation for the city and the New York Central. Pedestrians and vehicles could now cross unencumbered across Park Avenue, and the air was free of fumes and soot.

The New York Central then sold the “air rights” above the newly-covered Park Avenue to real estate developers at a handsome profit. These developers then built the great luxury apartment buildings that transformed the former eyesore street into the city’s most fashionable residential boulevard.

Finally, in 1914, under pressure from the city and a disgruntled public, the Pennsylvania Railroad made plans to follow New York’s lead and gradually retire their steam-driven commuter locomotives. Electrified trains, unlike their smoky predecessors, could operate safely underground. In the early 1900s, Pennsylvania’s president, the visionary Alexander Cassatt (brother of the Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt) led the push towards electrification. In 1910, the Pennsylvania Railroad put its first electrified trains into service, when their new Pennsylvania Station in New York City opened its doors. Incoming express trains from Philadelphia would stop at Secaucus, New Jersey. There, the steam locomotives would be detached and the train cars transferred to electric power. The trains would then travel the final leg under the Hudson River and glide silently into Pennsylvania Station’s soaring, glass-vaulted concourse.

Cassatt died in 1906, four years before the completion of New York’s Pennsylvania Station and its underwater tunnel system. His successors, most notably William Atterbury, continued Cassatt’s electrification crusade. Between 1914 and 1930 and using its own funds, the Pennsylvania Railroad electrified all of their 131 miles of commuter lines, a project that cost a grand total of $10 million. The first of these lines to be electrified was the most heavily traveled: the Main Line stretch between Paoli and Philadelphia. (xv) The last was the seventeen mile run between Philadelphia and Norristown. (xvi)

The company then constructed a new railroad bridge that spanned the Schuylkill River and led to a new tunnel eight tracks wide running parallel to the “Chinese Wall.” In 1930, the project was crowned by the Art Deco Suburban Station, located just to the north of the old Broad Street Station, which lost its trainshed to fire in 1923. As its name implied, Suburban Station would take over as Center City’s hub for travel out to the Main Line and the southwestern suburbs.

By the late 1920s, the Pennsylvania Railroad stated that even if Broad Street Station escaped the wreckers after Suburban Station was placed into service, its tracks would be fully buried as well. Railroad officials talked up big plans about replacing the “Chinese Wall” with a grand new “Pennsylvania Boulevard …with room for office buildings and other structures, a pleasing thoroughfare in the center of modern Philadelphia.” (xvii) However, the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing depression interfered with the Pennsylvania’s final plan to demolish Broad Street Station and deactivate its above-ground tracks. The damaged structure and the offending wall remained standing for two more decades.

Figure 6. Suburban Station on the left. Broad Street Station (minus the trainshed) and the “Chinese Wall” in foreground. Courtesy of PhillyHistory.org.

At 1:10 a.m. on April 27, 1952, as Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra serenaded onlookers in the main concourse, the last commuter train rumbled out of Broad Street Station and over the “Chinese Wall. (xviii)

The next day, wreckers began pulling down Frank Furness’s towering station and viaduct, and all commuter service was finally transferred to Suburban Station. This sweeping move opened up a vast swath of open space along Pennsylvania Boulevard for office and residential development. As workers demolished the old structures, city planner Edmund Bacon hired architect Vincent Kling to plan a new business district that would fill the void left by Broad Street Station. It was announced that the resulting redevelopment project would be “larger than New York’s Rockefeller Center.” (xix) The resulting Penn Center, a mixture of bland high rises, concrete plazas, and underground concourses, did become an important new business hub because of its umbilical connection with Suburban Station.

But as an urban renewal project, it failed to bring life back to the streets. Architectural critic Witold Rybczynski wrote scornfully of the Bacon-Kling collaboration: “The long term effect of ponderous, inward looking complexes such as Philadelphia’s Penn Center … on the surrounding streets life was deadening … a pallid accomplishment.” (xx)

The block-like office and apartment high-rises on the rechristened John F. Kennedy Boulevard, the old path of the “Chinese Wall,” were not much better in encouraging vibrant street life. Penn Center, although a grand gesture, was not enough to attract businesses back to Philadelphia. It was hoped that the Center City Commuter Connection would help fuel private redevelopment along the former path of the “Chinese Wall.”

The Construction of the Center City Commuter Connection

In 1978, after over ten years of lobbying by local officials, the Federal government agreed to pay for 80 percent of the project, with the state paying for 16.66 percent and the city paying 3.33 percent. (xxi)

According to Michael Griffin, a city engineer who worked on the project, at $330 million the Center City Commuter Connector was the most expensive federal transit investment project in America up to that time. This was also the first project funded under the “Full Funding Grant Agreement,” in which the city and state, not the federal government, were responsible for any cost overruns. This agreement became standard procedure for federal transit projects ever since.

The City of Philadelphia made its request in the nick of time. According to Chris Zearfoss of the City Planning Commission, federal transit funding was severely cut back in 1981 under the Reagan administration, and by that time the Center City Commuter Connection was well underway and safe from the cutting room floor.

Zearfoss said that “the project was funded on a cash-flow basis. There were twelve separate grant amendments made on a year-by-year basis. Back then, federal transit money remained very generous.” (xxii) Zearfoss also added that SEPTA “didn’t have the means to undertake this project.” (xxiii)

SEPTA was facing financial trouble and threatening to cut back service. To some, spending such a huge amount of money on a tunnel instead of using it to maintain existing service was a great waste. “Ironically, while the railroad is dying for lack of money,” wrote Frederick N. Tulsky of the Philadelphia Inquirer on May 21, 1981, “millions of dollars are being spent each month on the Center City Commuter Connection between Suburban Station and Reading Terminal. That $400 million tunnel would be useless if the service was terminated.” (xxiv)

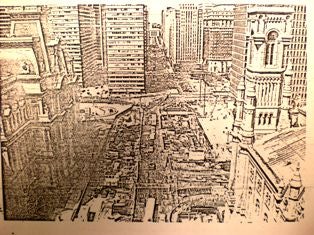

Penn Praxis director Harris Steinberg, then an architecture student at Penn, observed the construction process and did a series of drawings. He also had mixed feelings towards the project, scrawling at the bottom of one drawing: “This seems like a colossal effort for something that has a very limited market — suburban commuters. Perhaps though, with gas prices rising, the tunnel has the potential to be the salvation of the city, bringing suburban shoppers and commuters into Philadelphia and aiding in a much hoped for economic and cultural rebirth.” Steinberg then concluded, “Ed Bacon’s dream of 30 years is continuing its slow steps to fruition.” (xxv)

Figure 7. Cut-and-cover between City Hall and the Masonic Temple.

From the Project Engineer’s Report. Courtesy of Ruben David, P.E.

The excavation the Center City Commuter Connection finally commenced in 1978.

The project ultimately would hire 46 contractors and 300 subcontractors. (xxvi) The construction process was “cut-and-cover,” a technique pioneered in the 1890s for the construction of the New York City subway system. Workers would close the affected thoroughfares, dig track trenches anywhere from 30 to 71 feet deep, lay temporary wooden decking across the street, construct the tunnels, and then build a new street surface on top.

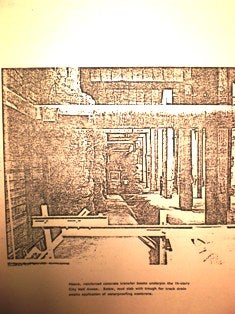

The first major challenge to this project was the building of structural underpinnings against the foundations of structures in the path of the Commuter Connector. These included the City Hall Annex, the old Essex Hotel, the Penn Square Building, and the Reading Terminal itself.

The 1893 terminal had to be replaced by a new, below-grade station in order for its tracks to meet those of Suburban Station. The Reading Terminal had no basement, and train service had to continue uninterrupted during construction. Workers had to cut the Reading Terminal’s original weight-bearing columns to make room for the new Market East Station. The old terminal’s weight was then shifted to temporary reinforced concrete transfer beams and caissons.

When the new Market East Station was complete, the supports were removed and the old Reading Terminal rested securely on the new, subterranean structure. (xxvii)

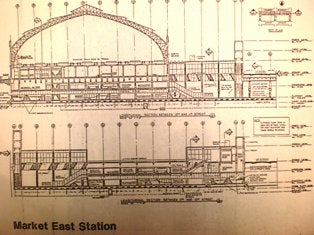

Figure 8. Cross Section of Commuter Connection Tunnels.

From the Project Engineer’s Report. Courtesy of Ruben David, P.E.

Figure 9. Cross-section showing the placement of Market East Station underneath the old Reading Terminal trainshed and market.

From the Project Engineer’s Report. Courtesy of Ruben David, P.E.

The most challenging building in the project’s path was the historic Masonic Temple. According to Griffin, “With other buildings we knew what to expect. Not so with the Masonic Temple. It had to be delicately underpinned by hand, and the methods did not always work the first time.” (xxviii)

Originally, concrete piers were constructed underneath the rubble foundations to shore up the structure. But according to the project report, the interior walls of the building started to crack. According to the engineering report, the solution was to build a “steel core concrete retaining wall of 95-pound steel tangent piles set in 24-inch diameter slurry-supported drill holes” protected against lateral settlement by “hydraulic flat jacks installed horizontally against the piles and actuated when tie-backs were removed during the forming of the tunnel wall.” (xxix) Griffin added, “When we had to stop and come up with new underpinning practices, this added to the cost of the project.” (xxx)

Figure 10. Photograph showing foundation underpinnings at the City Hall Annex. From the Project Engineer’s Report, Courtesy of Ruben David, P.E.

Ruben David, also a project engineer who was recently interviewed, noted that another challenge was protecting previously existing underground structures and features. “We had to protect and support a network of utility lines during the digging,” he said.(xxxi) The biggest of these underground structures was the Broad Street Subway, built in 1916 and according to the project report, “designed in anticipation of a rail line passing over it …Working just below heavy Center City traffic on timber decking the subway roof was demolished and the tunnel built while maintaining subway traffic on at least two of its four tracks.” (xxxii)

One special problem was dealing with archaeological sites located along the tunnel path. When a site thought to be of archaeological significance was found during construction, work would cease and an urban archaeology consultant would investigate the area. The most notable discovery was an African-American Cemetery at 8th and Vine Streets, near the original location of the First African Baptist Church, and “the only black pre-Civil War urban cemetery excavated outside the South.” In the end, archaeologists retrieved and catalogued 50,000 artifacts, mostly bowls, bones, and fragments of cloth. (xxxiii)

The final challenge was maintaining community support throughout the project. David maintained that it was crucial to “continue communications with the businesses on the street each day” on how the project was affecting them, and to “ensure the adequate protection of the pedestrians.” (xxxiv)

Conclusion

When the Center City Commuter Connection was completed in 1984, Philadelphia became the first city in the nation with a truly integrated commuter rail system, besting even New York City. Manhattan, like Philadelphia, was served by two main railroad stations: Pennsylvania Station (the original terminal was torn down in 1963) and the New York Central’s Grand Central Terminal. Penn Station serves New Jersey and Long Island commuters, while Grand Central serves those bound for New York’s Westchester County and Connecticut.

The two stations were linked by subway, but the trip is not direct, requiring a transfer to the “S” shuttle between Times Square and Grand Central. Ultimately, Grand Central’s convenient location helped boost midtown’s real estate values and draw the center of business and finance away from Lower Manhattan. The area around Penn Station, located at 7th Avenue and 34rd Street, remained comparatively shabby and marginal.

The office building boom that followed the completion of the Center City Commuter Connection cannot be fully attributed to the completion of the new tunnel. However, there is no doubt that since 1984, the area once occupied and blighted by the old “Chinese Wall” has prospered. No longer besotted by soot and noise, and supplied with thousands of commuters traveling on both the old Pennsylvania and Reading lines, this area was ripe for growth.

“While the construction of the Center City Commuter Connection presented numerous challenges,” wrote Gary Fairfax of SEPTA in a January 25, 2008 email, “by creating a means for passengers to travel more effectively into and through Center City Philadelphia it enabled the further development of shopping malls, department stores, hotels and business complexes in the area … the City of Philadelphia experienced an economic rebirth while allowing passengers to expand their geographic borders.” (xxxv)

According to Chris Zearfoss at the Planning Commission, the transit system took a number of hits during and after the completion of the Center City Commuter Connection that decreased ridership from its 1970s levels. Before the two systems were connected, the combined system carried around 130,000 riders per day. Today, the system carries 15,000 fewer passengers, and the tunnel itself has never approaching having the 90,000 daily users predicted in 1970. (xxxvi)

There were three main reasons for the decline, which were independent of the tunnel. The first was a crippling labor dispute. A year before the completion of the tunnel, transit workers went on strike for 107 days, completely shutting down the system. The second reason was a series of service disruptions due to additional constructions, most notably the shutting down of much of the former Reading line between Brown Street and Wayne Junction for renewal and renovations. Many passengers opted to drive into Philadelphia rather than take shuttle buses. The third was a serious cash squeeze. When SEPTA assumed direct control of the commuter trains, they still leased the rails from Conrail, which charged much higher rates than its predecessors. The resulting fiscal crisis led to severe off-peak service cuts. Trains went from running from every half-hour to every hour, and fares went up 79 percent from 1976 to 1983. (xxxvii)

Despite the overall decline in ridership, there is little doubt that the construction of Center City Commuter Connection helped spur a second phase of office high rise construction. In the decade following the completion of the tunnel, a combination of rising real estate values, developer incentives, an improving economy, and the newly unified suburban transit system caused a surge of new office building construction around Market Street and JFK Boulevard.

These economic forces pushed skyscrapers higher beyond the hat of Billy Penn atop City Hall for the first time, violating the old gentleman’s agreement. The first, of course, was Rouse’s Liberty Place, finished in 1986 at 17th and Market on a lot formerly occupied by “parking lots and a group of nondescript buildings.” (xxxviii)

Following the approval of Liberty Place, Mayor Wilson Goode proposed a plan that allowed for more tall buildings to be erected in an eight-block zone between JFK Boulevard and Chestnut Street. (xxxix)

More high rises followed, now directly on the footprint of the “Chinese Wall.” The Blue Cross-Blue Shield Building, topping out at 45 stories and echoing Liberty Place’s shape, was completed in 1990. That same year, the 54-story Mellon Bank Center arose across Market Street from Liberty Place, joined soon after by the 53-story Verizon Tower at 18th and Arch Street.

An irony is that the cursed “Chinese Wall” might have actually saved many of historic houses and office buildings along the old commercial corridors of Chestnut and Walnut Streets. Because these high rises were built on land long occupied by the viaduct, fewer historic structures had to be sacrificed to construct them than if they were built south of Market.

In addition, the residential population of Center City East increased by 16 percent between 1980 and 1990, and by 14 percent in the following decade. Zearfoss also notes that although Center City West’s population has remained fairly constant during the same time period, the housing boom has fueled immense population growth since 2000. (xl)

Today, the Comcast Tower is nearing completion at 17th and JFK Boulevard, on a lot which sixty years ago would have been one of the least desirable in the city. It is only fitting for there to be an underground pedestrian connection between the headquarters of present and past city corporate leaders: the Comcast Tower and Pennsylvania Railroad’s old Suburban Station.

Footnotes

i. As quoted by Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

ii. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

iii. Interview with Chris Zearfoss, Office of Strategic Planning, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, January 29, 2008.

iv. “A Tunnel is Sought for Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 5, 1970.

v. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

vi. The New York Daily News, October 30, 1975.

As quoted by Joshua Zeitz, “New York on the Brink,” American Heritage, November 26, 2006. http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/web/20051126-new-york-city-gerald-ford-labor-unions-municipal-assistance-corporation-emergency-financial-control-board.shtml

Accessed January 14, 2008.

vii. “A Tunnel is Sought for Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 5, 1970.

viii. Interview with Michael Griffin, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

ix. Interview with Michael Griffin, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

x. “A Tunnel is Sought for Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 5, 1970.

xi. As quoted by “A Tunnel is Sought for Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 5, 1970.

xii. As quoted by “A Tunnel is Sought for Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 5, 1970.

xiii. Urban Renewal in Philadelphia: Vincent Kling and Penn Center

http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/archx/05-600/proj/p2/fwda/Front_Page/web-content/Chinese_Wall.html

Accessed January 8, 2008.

xiv. Nathaniel Burt, The Perennial Philadelphian: The Anatomy of an American Aristocracy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 1963, p.529.

xv. “Opens New Electric Line: P.R.R. Completes Work on Suburban Service at Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 30, 1930.

xvi. “Opens New Electric Line: P.R.R. Completes Work on Suburban Service at Philadelphia,” The New York Times, July 30, 1930.

xvii. “Pennsylvania Railway Plans for Far Future,” The New York Times, November 18, 1928.

xviii. “Philadelphia to Lose Broad Street Station,” The New York Times, February 22, 1952.

Harry Kyriakodis, “Suburban Station.”

http://www.stationreporter.net/suburban.htm

Accessed January 16, 2008.

xix. “Philadelphia to Lose Broad Street Station,” The New York Times, February 22, 1952.

xx. Witold Rybczynski, as quoted by Critique of Penn Center

http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/archx/05-600/proj/p2/fwda/Front_Page/web-content/Critique.html

Accessed January 8, 2008.

xxi. Interview with Michael Griffin, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

xxii. Interview with Chris Zearfoss, Office of Strategic Planning, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, January 10, 2008.

xxiii. Interview with Chris Zearfoss, Office of Strategic Planning, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, January 10, 2008.

xxiv. Frederick N. Tulsky, “Feud May Derail Commuter Trains,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 21, 1981.

xxv. Harris Steinberg, AIA, Construction Notebook, Spring Semester 1980, Architecture 500. Collection of Penn Praxis.

xxvi. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

xxvii. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

xxviii. Interview with Michael Griffin, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

xxix. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

xxx. Interview with Michael Griffin, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

xxxi. Interview with Ruben David, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

xxxii. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

xxxiii. Engineer’s Report: Center City Commuter Rail Connection, UMTA Project No. PA-03-0013, PennDOT Project No. CA-5, City Project Number No. 20-590-2-8, 1985., n.p.

xxxiv. Interview with Ruben David, Center City Commuter Connection Project Engineer, January 17, 2008.

xxxv. Gary Fairfax, SEPTA Press Officer, Email correspondence, January 25, 2008.

xxxvi. Interview with Chris Zearfoss, Office of Strategic Planning, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, January 29, 2008.

xxxvii. Interview with Chris Zearfoss, Office of Strategic Planning, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, January 29, 2008.

xxxviii. Peter T. Leach, “Philadelphia: Rouse Towers Aim to Break Mold And Revivify Center City Streets,” The New York Times, May 12, 1985.

xxxix. Peter T. Leach, “Philadelphia: Rouse Towers Aim to Break Mold And Revivify Center City Streets,” The New York Times, May 12, 1985.

xl. Interview with Chris Zearfoss, Office of Strategic Planning, Philadelphia City Planning Commission, January 29, 2008. Citing United States Census of 1980, 1990, and 2000.

Contact the reporter at steven.ujifusa@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.