Grappling with the reality of I-95

Jan. 09

(This is the fourth in a series of stories examining the infrastructure projects proposed in the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware, and how they will solve the question of funding. This story looks at one of the biggest challenges in the Penn Praxis plan: what to do with Interstate 95.)

Previous stories:

Infrastructure overview

Parks and green space

SEPTA funding

By Alan Jaffe

For PlanPhilly

Since its inception nine months ago, it has been the most publicized proposal for reviving the Central Delaware waterfront.

To reach the river, we’ve got to get rid of the moat. Interstate 95 is a gaping maw in Center City and a Berlin Wall to the north and south, a physical and psychological barrier that prevents access to and development on the water. We need to cap it, bury it, subvert it, or reroute it.

It was the Big Idea to emerge from the Penn Praxis charrette last March, a rallying cry for planners and designers who were charged with reviving the city’s eastern shore.

But the Big Idea was met with a Big Chill from state, regional and local officials who warned that the funds did not and would not exist for an estimated $10 billion Boston-style Big Dig in Philadelphia.

When a commuter bridge collapsed in Minneapolis on Aug. 1, killing 13 people, government planners around the country were reminded that repairs to aging bridges, roads, utilities and transit lines were an immediate priority. And there were only so many infrastructure dollars to go around.

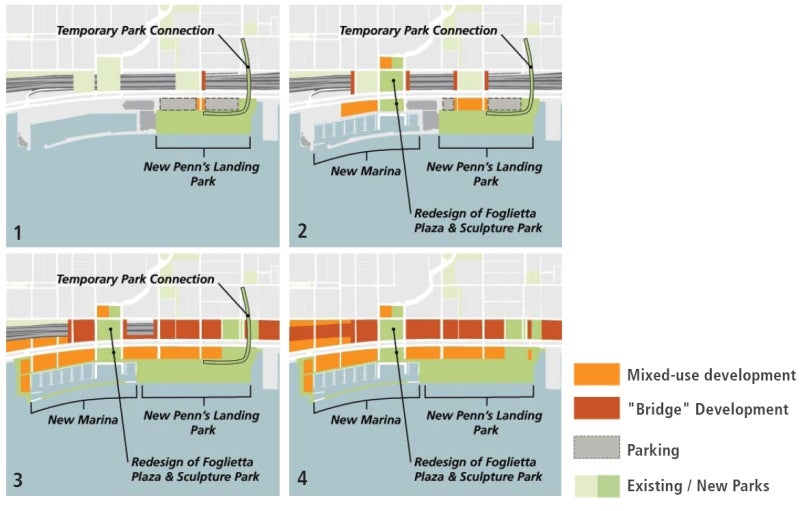

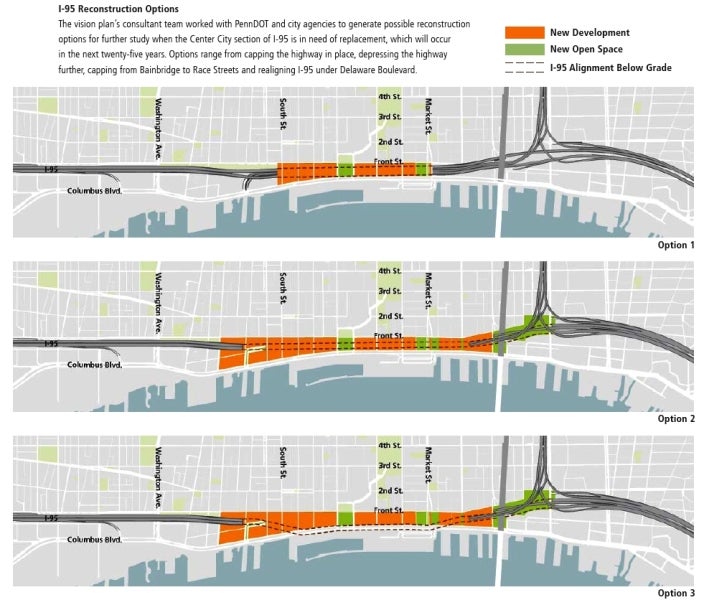

When the Civic Vision for the Central Delaware was officially unveiled in November, I-95 still had a starring role. But there were now three options for the central portion of the highway, two that proposed depressing a large section and one that called for a more modest rebuilding and capping of the road.

“Is there a way to sink it? I don’t know. There is lots more study to be done,” Penn Praxis executive director Harris Steinberg told the audience at the Pennsylvania Convention Center. “This is something that the plan doesn’t live and die on.”

But, he also said, “This is where we have to think big.” Remaking I-95 could prove to be “a transformative investment for the city.”

Economics and Access

While opponents of the I-95 proposal point to the cost, proponents talk about cost benefit.

“The economic value of the waterfront is based on the connectivity from the city to the river,” according to Nando Micale, a senior associate at the design firm Wallace Roberts & Todd. “There is value in the land now occupied by 95,” and the overarching reason to change the highway is “economic development.”

Plans for developing the prime real estate around Penn’s Landing have gone largely unrealized. Over the past four decades, nearly a dozen ambitious proposals, including multi-billion-dollar dreams of multi-plexes, science centers, water parks, skating rinks, residential, retail and office space have flared and fizzled. A few waterfront attractions were built and survive, including the amphitheater,

Independence Seaport Museum, some condos and a few restaurants. But the site’s potential has never been met.

The Civic Vision’s approach is to take “what’s been successful about the evolution of Center City over time, and bring it all the way to its greatest asset, which is the water,” Micale said. “The reason why 95 is viewed in this vision plan so differently from previous proposals is that [older plans] had conceptualized the waterfront as a destination. This vision conceptualizes it as an extension of the city. The best way to extend the city is to literally extend it, right over 95.”

The two most extensive options in the Civic Vision would create nearly 36 acres of developable land above and around 95. The more modest proposal will result in almost 17 developable acres.

Rather than attractions like movie theaters or a Camden-Philadelphia tram, the Civic Vision calls for mixed-use development, including scattered high-rises and street-level retail and restaurants erected over the highway, anchored by a 12-acre public park at the water’s edge.

The Options

When I-95 was originally planned in the 1950s, it was intended to be an elevated highway all the way through Philadelphia. But prescient architect Frank Weise warned city planners that the road would sever the city from the river. Community leaders in Old City and Society Hill also added pressure to depress the highway in the central section.

The final result was “this spaghetti” that links I-95 to the Vine Street Expressway (Route 676), with the Market-Frankford line emerging from the ground, and the Ben Franklin Bridge coming down above it all, Micale said. “So you have this web of roadway and infrastructure coming together … It was this engineering feat to try and suppress it but make the connections, and go under the bridge and over the rail.

“So that’s how we ended up with what he have now. Since it was a reaction to what was being proposed, which was all elevated, you end up with half-designed things,” Micale said.

“Probably in an ideal world, if the city and state had looked at multiple options, you’d want to put all of it underground,” he continued. And that was discussed at the March charrette, when a team of designers suggested continuing 676 underground and connecting it to a depressed I-95. That proposal was taken off the table, Micale said, because 676, which was built in the late 1980s, would not be rebuilt for generations to come.

The schedule for changes on I-95, however, are not so far on the horizon.

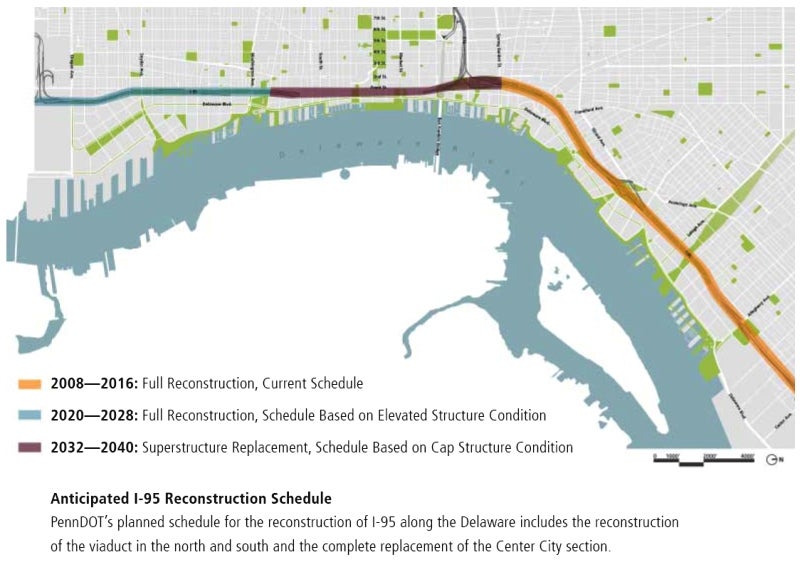

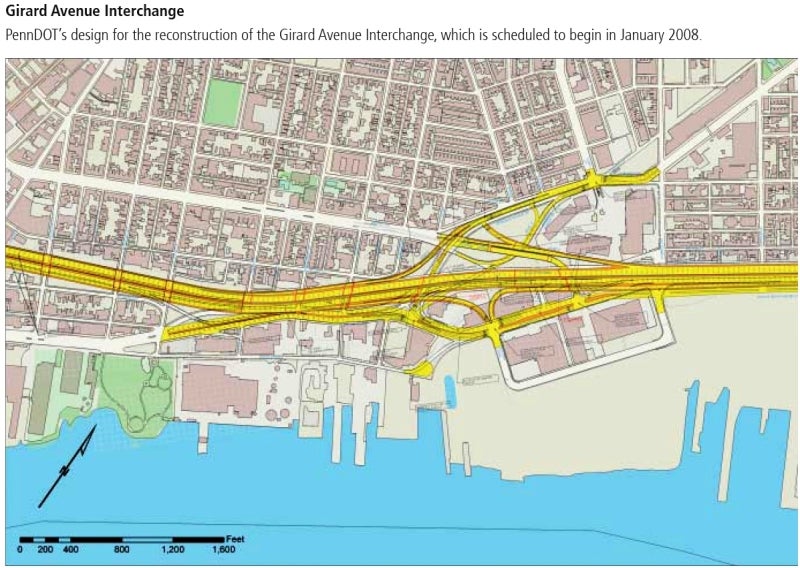

The Pennnsylvania Department of Transportation timeframe for rebuilding the northern portion of the state highway, from Spring Garden Street, is 2008 to 2016, and it will include a total reconstruction of the Girard Avenue Interchange. From 2020 to 2028, the section of the highway south of Christian Street is scheduled for reconstruction.

The central section is due for its rejuvenation in 2032 to 2040. “We’re talking not about our children, but our grandchildren” enjoying the eventual benefits of what’s envisioned now, Micale said. That leaves plenty of time to discuss and plan for the possibilities.

The first option for the central portion in the Civic Vision is to rebuild about .65 miles of the highway “in place, but suppressed from Market Street to South Street. This is a minor depression,” Micale said. “This could actually be accomplished without depressing it,” but with capping the road. “What you would get, though, is a hump of development. Right now, all the streets and walkways and bridges go up and over.”

A 2003 study by WRT for a group of waterfront community organizations took the same approach. That study recommended raising a section of Columbus Boulevard to mitigate the difference in the elevation of Front Street. “That would still be a major reconstruction,” Micale said, “but it would focus on bridging over the rail lines and redoing Columbus Boulevard.”

The second option would be a major depression of 1.46 miles of I-95 beginning at Callowhill Street in the north. The highway would be capped from Race Street to Bainbridge Street.

This option still requires more data from Septa and PennDot and a survey of the ramp connection system, Micale said.

The third option is an “infrastructure-driven decision,” Micale said.

“If you’re going to rebuild 95, does it belong there? Or do you rebuild it as part of reconstructing Columbus Boulevard, so that you put 95 under the boulevard?” This option would realign the highway under the boulevard in a tunnel. All the land occupied by the highway now would become developable under this option. Portions of the land could be used for “basement levels of parking, on top of which development occurs.”

“That is the most ambitious plan,” Micale said.

To the north and south of the central section of 95, the plan finds value underneath the existing highway. PennDot’s plans to rebuild the Girard Avenue Interchange and a portion of the highway in South Philadelphia will create opportunities to reconnect neighborhoods to the waterfront and take advantage of ramp and lane reconfigurations.

The state already leases portions of the underside of the 95 viaduct for parking, Micale noted, and has utilized other sites for recreation, including the Rizzo Ice Rink at Washington Avenue in South Philadelphia. Ideas for the underside of the highway aren’t new, “but we’re saying perhaps they should be implemented as a policy because it’s good urban design.”

In the north, the reconstruction of the Girard Avenue Interchange, at an estimated cost of $525 million, will remove or consolidate ascending and descending ramps and open up the area to various “opportunities for found amenities,” such as earthen embankments, stormwater management, green walls, parks and parking space, recreational trails, and other civic uses beneath the highway, Micale said.

“The same way that the land is valuable on top” in the central portion of the city, to the north and south “the land is valuable underneath for different things.”

Official Reception

When the proposal to bury I-95 was suggested back in March, it was met with a mix of excitement and disbelief. The idea captured the imagination of the city; fiscal realities kept it from flying too high.

Barry Seymour, executive director of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, called the proposal “a great vision,” but “a huge financial burden” and “a tough sell.”

Gary Jastrzab, acting executive director of the City Planning Commission, called the I-95 proposal “one of the biggest and most important and attractive ideas of the entire plan.” He also said it would be “hugely costly” and he worried about what municipal projects would be lost at its expense.

The highway itself has been the responsibility of former state and PennDot Deputy Secretary Rina Cutler, who was transportation commissioner when Boston undertook its $14 billion Central Artery/Tunnel Project.

Cutler was recently named Philadelphia’s deputy mayor for transportation and utilities. She also was director of parking and traffic when San Francisco remade its waterfront highway, the Embarcadero.

But she doesn’t see parallels between those urban success stories and the proposals for I-95.

“I think that if the focus of [the Vision Plan] is I-95, it will sit on the shelf along with the other waterfront plans that have been made,” Cutler said in an interview a week before the Penn Praxis plan was officially unveiled. “That’s not to say as we move along and start to look at the redoing of 95 along the entire corridor that we won’t look at it. But we’re assuming something like a $10 billion price tag to put 95 underground. So I think the chances of it happening are pretty slim.”

Cutler does not hold out much hope for the most modest option in the Vision Plan either. “There is no such thing as a minor depression on an interstate highway,” she said.

When the central segment of the highway was built, it was meant to have a cap, Cutler said. “The fact that it doesn’t indicates there was either an issue with how one would vent the fumes, or there was some other issue. …So I’m assuming there was a good reason for it not happening.”

Is the first option still a more viable choice? “It is. But the thing that has changed since that was built is the homeland security aspects of building tunnels, which have significantly changed since 9/11. And as recently as [October] when a multiple-car pileup in California in a tunnel caused huge damage, the question of how you would design that with the appropriate escape routes would be another challenge.

“That’s not to say it can’t happen,” she said. “But the central I-95 piece will happen, I suspect, as part of looking at the interstate as a whole. It is my belief that it is likely to substantially stay as is.”

Cutler has heard the view that the highway is “this horrible scar on the landscape, and I suppose from an aesthetics perspective it would be a lot better if it wasn’t there. But from a traffic perspective it does what an interstate highway is supposed to do, which is carry people and goods interstate” – as many as 190,000 vehicles a day.

Charles Denny, chief traffic engineer for the Philadelphia Streets Department, is responsible for handling the effects of any I-95 reconstruction.

The city is currently considering what will happen when PennDot begins work on the Girard Avenue Interchange. I-95 will remain open during that work, he said, but “a fraction of the traffic will be diverted. The exit lane traffic would go to local streets, and they would be able to handle that traffic,” he said.

During the Big Dig in Boston, the cross-town highway remained open, he said. “But it would be costly to do it that way. There are many things that are feasible, but not economic.”

It was traffic that motivated the 20-year effort in Boston, Cutler noted. “I think the Big Dig’s primary mission at the time it was built was to increase capacity in order to move traffic. A sidebar happened to be that the only way to do that was to bury it.”

While other cities are considering depressing waterfront highways, few are actually doing it, Cutler continued. “San Francisco, another city I spent three years in, did it because the earthquake knocked down” the highway. “I do not believe that under other circumstances that would have occurred,” she said.

“If you look at other places that have created, for lack of a better term, a river road along the side of the water, I don’t know how many of them are interstate highways. So the ability to do something different along Delaware Avenue is a very different equation than doing it on an interstate highway.”

Nor does Cutler believe reconnecting Center City to the river depends on what happens to I-95. “I think that if there was something at the waterfront that people wanted to go to, [the state highway] would not interfere with that happening. Part of the reason why people don’t use the waterfront is, except for a handful of special events, there is no reason for people to use the waterfront,” she said.

Cutler does agree with proposals in the Vision Plan for the northern and southern sections of the highway. “I think there are some places in its current configuration that allow streets to get connected under it, and to be able to make the connections between the neighborhoods and the water, and I think wherever that happens we should try to incorporate that into the design. But highway design is very different than building design, landscape design, waterfront design – and it has a whole lot of very stringent requirements on the federal side,” Cutler said.

Work on the Girard Avenue Interchange will go out to bid before the end of the year, she said, and a lot of discussion has occurred with planners and civic groups about a redesign that would have the least negative impact on the community. “Whether it looks exactly like it does in WRT’s visuals, I won’t promise. But we think that from an aesthetic as well as a transportation enhancement perspective, that is a very good site to try to get the river and the neighborhood back together.”

As for the central section, any option must surmount the financial obstacles. The Boston project had plenty of federal money and a Congressional patron in Tip O’Neill. Those circumstances don’t exist for Philadelphia or Washington today, Cutler said.

So where could the funding come from? “We have no idea. There is certainly a way federal transportation dollars work. There is by formula a certain amount for the state of Pennsylvania. And then the five-county Philadelphia region, by formula, also gets a specific amount. But there’s not enough money in that pot to handle the current problems with the infrastructure. So I don’t believe most or much of that can be used for this. I don’t believe that there is any identifiable source at this point for burying I-95.”

Cutler said the proposed options for I-95 also need more study. “I do not know from either an engineering or an environmental perspective what’s doable and what isn’t. I do not know from a financial perspective what might be able to be pulled out for potential development rights. I don’t know whether or not the notion of tolling I-95 and using some of that revenue to pay for this would ever be considered. So there is no source of dollars, at this point, that would come anywhere near what it would cost to do this.

“It’s pretty easy to say we should absolutely do it, and people like me will say, ‘Great. How’s that going to happen?’ It’s the difference in some ways between being a planner and being an implementer. Planners get to create wonderful visions, and implementers get to worry about how that could happen.”

Money and Politics

WRT’s Micale agrees that the possibilities for altering I-95 depend on “finding the right financing structure to make it happen.”

The other challenge is building “political will, because that’s how costs get figured out,” he said, and echoed Cutler: “There’s no more Tip O’Neill.” But whether the city figures out a way to use tax increment funding, or creates some other funding stream to leverage other money, “as we look toward the future of cities, the national policy toward investment in infrastructure should shift as well.”

Urban areas have the highest concentration of people, he said, “and there should be different standards for making those types of investments, as opposed to investing in unsustainable development practices.”

There still needs to be further study on various levels, said Steinberg, of Penn Praxis. “We need to test the economic and engineering and environmental feasibility of various methods of treating I-95. There is a lot more detailed investigation that needs to happen before there’s even a determination if it’s feasible,” he said.

“Right now, it’s a vision. People understand it, and they understand the benefits. But we haven’t fully explored what the implications are, financially, politically, and otherwise.”

Next: Costing out the street grid

Alan Jaffe is a former Philadelphia Inquirer editor. Contact him at alanjaffe@mac.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.