Gloria Dei: a parish for the ages

By Steven B. Ujifusa

For PlanPhilly

The Mission of Gloria Dei ‘Old Swedes’ Church is to worship God and to honor and celebrate the differences and unique qualities of the members of our congregation; to be an inviting, welcoming, sustaining and loving community; to respond to the needs of others; and to preserve and build upon the beauty, tradition and heritage of this sacred place(i).

– From the Mission Statement of Gloria Dei “Old Swedes” Church

A Place of Refuge on a Stormy Sunday Morning

The congregation of Gloria Dei “Old Swedes” Church was a hardy bunch on the stormy morning of Sunday, April 15. The rain pounded down in sheets on the small brick church and its surrounding cemetery and rectory. Nonetheless, upon entering the sanctuary, it was hard not to be was struck by the lightness and airiness of the space. The Hook and Hastings organ bellowed out the first hymn in a throaty voice. The space was brightened by the glow of brass chandeliers hanging from the ceiling and large windows letting in plenty of light. Two models of the sailing ships that carried the first Swedish settlers to the Delaware Valley in 1638 and two shimmering angels perched on the organ loft–brought over from the old country by those same intrepid pioneers–hovered over the pews. Flowers from the previous week’s Easter service cascaded down from the altar and sat perched on the window sills.

As Reverend Joy Segal, dressed in flowing white vestments, raised the communion chalice and proclaimed the benediction, the Delaware River and its freight piers loomed through the chancel windows, reminding the worshippers that Gloria Dei was founded by settlers whose souls had been shaped by ships and the sea since the days of the Vikings.

Today’s congregation comes from as near as the adjoining row houses of Queen Village and as far away as the suburbs of South Jersey. They are teachers, small business owners, families with small children, and retirees. This is an informal place. The congregants do not feel out of place in jeans and sweatshirts. Children sit in the pews playing next to their parents. As Episcopal services go, Gloria Dei is decidedly Low Church. There are no processions, incense, or sung psalm chant. The liturgy is spoken rather than sung. The emphasis is placed on readings from scripture and congregational hymn singing. Midway through the service, members of the congregation get up in their pews to make individual announcements about events such as the upcoming Flea Market on the grounds and updates about the health of sick parishioners. The congregation reads responsive psalms by alternating the readings to the left and right sides of the aisle.

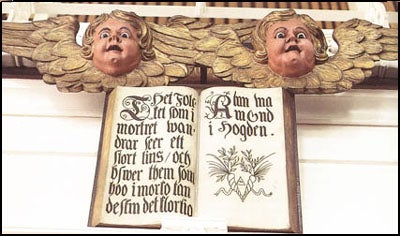

Two angels and a Swedish hymnal carved in 1646 and perched on the organ loft. This fine example of Swedish folk art was brought over from Sweden by the original setters.

http://www.old-swedes.org/grounds_bld.cfm

Although it is informal and small in size, Gloria Dei is a vital, proud and welcoming place, a sacred patch of ground wedged between Christopher Columbus Boulevard and I-95. The congregants are proud of being able to worship in Philadelphia’s oldest surviving church, belonging to a congregation with roots that predate William Penn and the Quakers by nearly half a century. It is one of only 77 National Historic Sites in the nation, a distinction shared with such august properties as Independence National Historic Park and the Statue of Liberty & Ellis Island National Monument.

Among Philadelphia congregations, Gloria Dei is remarkable not just for being the oldest, but for having a history and congregational make up that has spanned many neighborhood incarnations. Completed in 1700, the church started out as the spiritual center for the area’s Swedish Lutherans. After joining the Episcopal Church in the mid-19th century, Gloria Dei still remained a church tied to the life of the sea, as it was joined by the masts, steam whistles, and bawdy sailor entertainment of Front Street and the Philadelphia Navy Yard. As nautical life along the Delaware River receded during the 20th century, the church was a beacon of faith and history in a South Philadelphia wracked by urban decay and violence, a community cut off from its traditional lifeblood by the concrete barricade of I-95.

History

The Swedish settlement of the Delaware Valley is one of the great, forgotten chapters of Pennsylvania history. If one were to strictly define Philadelphia by the date of its earliest settlement, it should be known as the Viking City, not the Quaker City. The settlers who founded Fort Christina (later Wilmington, Delaware) and the colony of New Sweden in 1638 were not members of an off-shoot, persecuted sect such as the Quakers. Rather, they were mainstream Lutherans seeking a better life in the fertile estuaries and farmlands of the Delaware Valley. The Swedes, alongside the English and the Japanese, can rightly lay claim to be among the great seafaring nations in history. This is reflected in Gloria Dei, whose history is integrally tied to the waterfront.

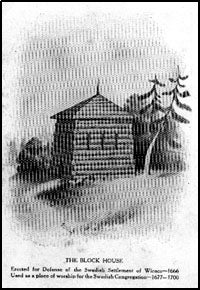

The original Gloria Dei “Old Swedes,” built in 1666 as a wooden blockhouse and converted into a church in 1677. www.old-swedes.org/history_founding.cfm

The settlement of Wicaco was named for a derivation of a Native American phrase for “peaceful place.” The settlement around Gloria Dei was first populated by Swedish settlers in the 1640s from the capital of New Gothenberg on Tinicum Island under the leadership of Governor Johan Printz, offshore from present-day Essington (ii). By the mid-17th century, the settlement of Wicaco was dotted with sturdy log cabins–a Scandinavian contribution to the American landscape–and the Delaware waterfront was lined with the descendants of the Viking long ships. The streets and docks resonated with the clanking of blacksmith forges, the hammering of shipwrights, the shouts of sailors, and the scraping of Swedish fiddlers.

The original Gloria Dei church was constructed in 1666 as a simple log block house that reflected the rugged building practices of its congregation’s native land, similar to those of the study and functional log cabin houses that dotted the streets and fields of the Wicaco settlement. The present-day church on the site, dedicated on July 2, 1700 by Pastor Andreas Rudman, was constructed by English craftsmen who had come to settle in William Penn’s settlement of Philadelphia directly to the north of Wicaco.

Charles XII (reigned 1697-1718), King of Sweden at the time of Gloria Dei’s construction. His military ambitions eventually cost him his life and Sweden’s empire, and also ruined his country’s economy.

By the time of Gloria Dei’s dedication, a series of brutal wars waged between Sweden’s war-loving King Charles XII and Russia’s Czar Peter the Great had sapped Sweden’s manpower and treasury(iii). This led to a decline of Sweden’s once-mighty European empire and a loss of interest by the Swedish crown its American colonies. By the early 1700s, the British settlement of Philadelphia to the north, made up of Quakers and Anglicans, dominated the Delaware Valley and annexed what was left of New Sweden. Wicaco was renamed Southwark by the Pennsylvania colonial government. By the mid-18th century, Southwark had lost its rural, maritime village charm and had become a neighborhood of dense row houses and shops.

Not all were pleased with the “progress” that came with Wicaco’s incorporation into the British Empire, particularly the original Swedish population. In 1743, Secretary Peters complained to Governor Thomas Penn:

Southwark is getting greatly disfigured by erecting irregular and mean houses; thereby so marring it’s beauty that when he (Thomas Penn) shall return he will lose his usual pretty walk to Wicacco [sic](iv).

The Philadelphia Navy Yard was originally located just south of Gloria Dei, which is shown in the background in this c.1800 print from the Independence National Park Collection. http://www.qvna.org/qv/history.htm

Despite New Sweden’s incorporation into the British Empire and later the new American Republic, William Penn’s original Charter of Privileges allowed the Swedish Lutherans to freely practice their faith alongside British Anglicans, Irish Catholics, and Sephardic Jews (v). Southwark Village, which comprises much of present day Queen Village and Bella Vista, remained a completely separate municipality until the 1856, when Philadelphia finally annexed its smaller Swedish-born sister with the Act of Consolidation (vi).

In the same way the Swedish settlement was swallowed up by the Anglo-American city of Philadelphia, Gloria Dei gradually lost its Scandinavian Lutheran congregants. Finally, in 1845, Gloria Dei severed its official spiritual ties to the Old Country and joined the American Episcopal Church.

However, the ties binding Gloria Dei to its original seafaring heritage grew even closer during the 19th century. In 1800, President John Adams and the Federalists, as one of their final acts before being tossed out of power by the anti-military Jeffersonians, ordered the construction of the Philadelphia Navy Yard just down the street from Gloria Dei. The Southwark Navy Yard, as it has become known, produced many of the U.S. Navy’s finest sailing frigates and steam warships from 1801 to 1867, when a fire destroyed it and the facility was moved to League Island (vii).

Reverend Sndyer Binns Simes, Rector of Gloria Dei from 1868 to 1915. Although the area around his church became largely working class and industrialized, the congregation prospered.

The Navy Yard caused a boom in construction and industry in the area around Gloria Dei, as thousands of immigrants swarmed into South Philadelphia looking for jobs. During the second half of the 19th century, the blocks beyond Gloria Dei’s gated cemetery truly became a noisy, industrial and smoky waterfront neighborhood. The Delaware River was lined with sailing ships and steamers, and the row houses and tenements surrounding the church became filled with immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Even after the closure of the Southward Navy Yard in 1867, industry continued to boom in the area, particularly along 4th Street, which became known as Fabric Row because of its flourishing textile industry.

But South Philadelphia’s growing economy did not lead to pleasant conditions for many of its residents. The familiar late 19th century urban problems in all their horror in the area around Gloria Dei: poverty, child labor, overcrowded housing, poor sanitation, and disease.

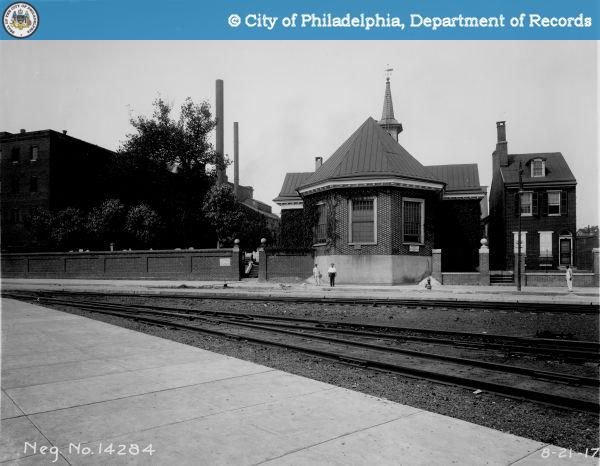

A 17th century maritime church meets the railroad. Gloria Dei church and rectory in 1917. www.phillyhistory.org

Despite (or possibly because of) its location in a bustling industrial neighborhood, Gloria Dei thrived during the late-19th and early-20th centuries, both as a house of worship and a place of urban outreach and ministry to the poor. Under the leadership of Rector Snyder Binns Simes, the church’s physical plant was expanded and improved, most notably with the installation of a first-rate Hook and Hastings organ. The church was well attended and the Sunday school thrived (ix).

The interior of Gloria Dei c. 1900, as seen from the organ loft and facing the altar and the Delaware River. To the right of the altar stands an 18th century Swedish baptismal font. The side balconies were added in the mid-19th century to accommodate the burgeoning congregation. The church’s interior today is almost entirely unchanged from this image.

However, following World War II, Gloria Dei and its congregation had to weather a trio of disasters that almost tore Philadelphia apart. The first blow was the familiar tale of the decline and eventual collapse of the city’s manufacturing economy, as factories closed or moved where labor costs were cheaper. South Philadelphia was particularly hard hit, and the construction of new but poorly planned housing projects in the vicinity of Gloria Dei made matters worse. According to the Queen Village Neighborhood Association:

Locally, several blocks between Christian Street and Washington Avenue (3rd to 5th Streets) were cleared to create the Southwark public housing project. Initially a model for urban renewal, the three large apartment towers quickly fell into disrepair and became a haven for drugs and crime (x).

The second blow was the flight by many residents of the tight-knit, dense row house blocks to the clean but bland middle class suburbs in South Jersey and Delaware County. The third blow, and perhaps the cruelest to Gloria Dei, was the construction of I-95 immediately to the west, severing the church from the neighborhood that had sustained it for two-and-a-half centuries. This construction project ravaged the historical fabric of Gloria Dei’s surroundings, destroying hundreds of 18th century homes (xi).

During the last decade of the 20th century, under the leadership of Reverend David Buchanan Rivers, Gloria Dei began to rebuild its congregation as a new group of artists, writers, teachers, and young professionals starting moving into the shattered neighborhood, which was renamed Queen Village in honor of Queen Christina of Sweden.

The Life of Gloria Dei “Old Swedes” Church in the 21st Century

According to the church’s mission statement, Gloria Dei’s goals are two-fold. The first is to continue its spiritual mission and to care for its congregation and community as a 21st century urban church. The second is to act as a steward for one of Philadelphia’s most important historic sites, one that is irreplaceable both in terms of its historical value and its architectural significance. It might be this rare combination of spiritual drive and earthly purpose that has helped sustain Gloria Dei through some very trying times for historic urban congregations.

Despite its age, one of the marvels of Gloria Dei is that it has survived for three hundred years with few significant “modernizing” alternations that would detract from its original 17th century construction. Gloria Dei is an exercise in ruggedness, simplicity and elegance. As a building, it makes no pretense to grandeur, although at the time of its construction it must have towered over the squat wooden houses of Wicaco. Although small in size and simple in detail, Gloria Dei shares a lot in common architecturally with the Anglican Christ Church at 2nd and Market Streets that was constructed twenty five years later. It is constructed in a simplified Georgian style, with red brick walls laid in a Flemish bon pattern, and white trim and window frames. Its west front is defined by a tall, white wooden spire. Like Christ Church, Gloria Dei is built in an open, meeting house style format, with no side aisles or crossing. The church’s interior tones are muted; its woodwork is painted white, and its ceiling robin’s egg blue. The church, rectory, and parish hall are surrounded by a tree-shaded cemetery and brick wall that from provides a refuge, not a barricade, from the row houses and piers of South Philadelphia.

The news events that are having a deep impact on the Episcopal Church in recent years, namely the ordination of homosexuals and the election of a female presiding bishop, are well known. In addition, the Episcopal Church has been gradually losing members. This decline has hit urban areas particularly hard, leaving once grand city churches with smaller and increasingly older congregations (xii). The resulting straitened financial circumstances faced by these urban congregations make it difficult to carry out ministry programs such as feeding the poor and operating day-care centers.

But Gloria Dei’s congregation, despite these present day controversies and having weathered three centuries of urban change and upheaval, has been able to devote itself to its mission and retain a strong, diverse and loyal congregation in the midst of the city. One factor that has helped its survival is, of course, its unique and rich history. Although few people of Swedish descent now sit in the pews, the church still celebrates the spiritual heritage of its original builders during Luciafest, the most important Swedish cultural event of the year. Luciafest takes place during Advent and involves the children of the congregation. According to Gloria Dei:

Luciafest, also known as the “Festival of the Lights”, is a musical extravaganza that is presented entirely in Swedish and in which most of the participants are children. Lucia has been a symbol of light and hope to the Swedish people since the Middle Ages, when she brought food to the hungry during a great famine. The modern Lucia is the eldest daughter of the family. She rises early on December 13 and carries a tray of cookies and sweets to each member of the family while singing the old Sicilian melody Santa Lucia and wearing a white robe tied with a crimson sash and a crown of lighted candles (xiii).

The children of Gloria Dei dressed up a festival.

http://www.old-swedes.org/events_special.cfm

The other, more powerful factor in the strength of Gloria Dei is its open and inclusive spiritual atmosphere, one that is welcoming to parishioners and visitors alike. A typical member of the congregation is Rita West, a South Philadelphia resident who works at Black Tie at 12th and Walnut. An Italian-American who was raised Roman Catholic, she came to Old Swedes and the Episcopal Church relatively late in life. Although she does not know much about the history of the building, what matters to her deeply is that Old Swedes is like a small family of approximately 200 people.

Reverend Joy Segal, current rector of Gloria Dei “Old Swedes” Church.

http://www.old-swedes.org/people_minister.cfm

West feels that the energy and personality of the new rector, Reverend Joy Segal, holds this family together. Segal was hired just over a year ago to replace Reverend David Buchanan Rivers, retired after thirty years of service to Gloria Dei. “She is A-1 quality,” said West during a May 4 interview. “Joy is a big factor in the church knowing its mission…When you see her pray or raise the communion chalice, she has an intense spiritual glow about her. (xiv)”

West adds: “This is a close-knit congregation full of warmth and joy, we all stick together. I’ve been to many churches in my lifetime, and this church is my comfort-zone.”

LINKS

Gloria Dei Old Swedes Church

http://www.old-swedes.org/

The church’s official website.

Queen Village Neighborhood Association

http://www.qvna.org/

More information on community life and news in Queen Village, particularly on reaction to the casinos.

American Swedish Historical Museum

http://www.americanswedish.org

Located at 1900 Pattison Avenue in a replica of an 18th century Swedish manor, this museum celebrates the Swedish-American experience.

The Kalmar Nyckel

http://www.kalmarnyckel.org/

The Kalmar Nyckel, based in Wilmington, is a working replica of the 17th century sailing ship that brought the first Swedish settlers to the New World in 1638.

———————————————————

(i) http://www.old-swedes.org/about_mission.cfm

(ii) Gloria Dei Old Swedes Church http://www.old-swedes.org/history_founding.cfm

(iii) http://www.pierre-marteau.com/resources/charles-xii-sweden.html

(iv) Queen Village Neighborhood Association http://www.qvna.org/qv/history.htm

(v) Gloria Dei Old Swedes Church

http://www.old-swedes.org/history_founding.cfm

(vi) Queen Village Neighborhood Association

http://www.qvna.org/qv/history.htm

(vii) The Philadelphia Navy Yard www.navyyard.org

(viii) Queen Village Neighborhood Association

http://www.qvna.org/qv/history.htm

(ix) Gloria Dei Old Swedes Church

http://www.old-swedes.org/history_simes.cfm

(x) Queen Village Neighborhood Association

http://www.qvna.org/qv/history.htm

(xi) Ibid

(xii) Female Chief Makes Church History

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/5093256.stm

(xiii) Gloria Dei Old Swedes Church

http://www.old-swedes.org/events_special.cfm

(xiv) Ibid

(xv) Interview with Rita West, Black Tie, May 4, 20

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.