How we manage our stormwater

May 3

By Kellie Patrick

For PlanPhilly

Homes topped with green roofs, parking lots paved with surfaces that let water soak through, and other techniques that reduce storm water runoff are becoming more common, said a group of national, state and local experts assembled for the Philadelphia Water Department’s Urban Watershed Conference.

But this region still has a lot of work to do before such flood-reducing, waterway-restoring building practices become the norm. And getting there will be neither easy nor cheap.

Federal and state regulations and statutes can serve as guides, but much of the work has to happen at the local level, said panelist Barry Newman, Department of Environmental Protection storm water planning and management section chief.

“The local level is where you have all of the necessary pieces: Land use control, building authority, construction oversight, the capacity to raise money, enforcement authority.”

Local control has split Pennsylvania into thousands of municipalities, all doing things in their own way at their own pace.

Many counties are working on a county-wide storm water plan, Newman said, and Bucks County is close to putting one in place.

But right now, “Municipal response is scattered,” said panelist Paul Leonard, Township Manager of Upper Dublin Township in Montgomery County. Municipalities have not been set up around watersheds or other environmental issues, he said, and while they are trying to do a lot, the efforts have largely been uncoordinated. “Many municipalities have adopted regulatory standards after the horse has been let out of the barn.”

The panelists said that some local variation would always be necessary, since communities are so physically different across the state. However, less variation would help developers, since they could use the same, water-friendly methods again and again.

There are grants available for municipalities to create storm water management plans.

But for Philadelphia and many older suburbs, a lot of damage has already been done over many decades.

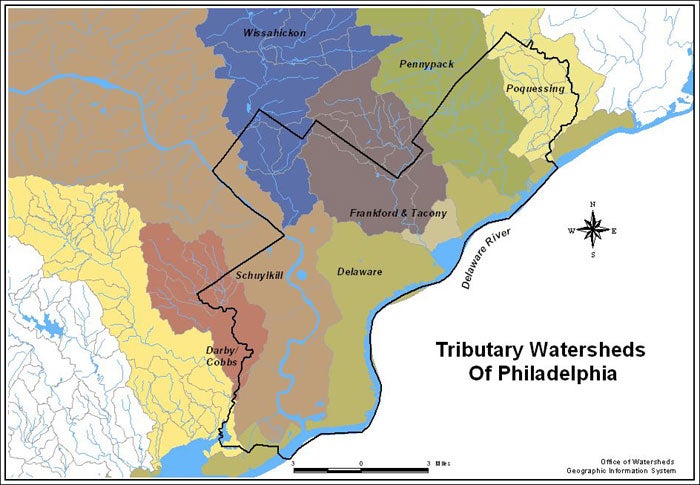

“The biggest problem we deal with in this region is that many of our watersheds are completely built up,” said Jeffrey Featherstone, Director of the Center for Sustainable Communities at the Ambler College of Temple University.

Fixing existing problems is expensive. And even residents who have been hit hard by the flooding do not necessarily want to pay for a fix.

“They say, ‘We’ve had enough of this. It’s been 30 years. We’re tired. Do something about it! But don’t raise our taxes,’” said panelist Eileen W. Mulvena, program manager for the municipal services division of NDI Engineering Company. NDI is the municipal engineer for six communities in Delaware County, including Darby, Yeadon and several economically depressed, inner ring suburbs.

So those who work at the municipal government level often look to redevelopment to fix old problems – and pick up the tab.

“We try to negotiate additional improvements, to try to get as much out of each developer as we possibly can,” Mulvena said.

Philadelphia’s Water Department is also looking to redevelopment to help remedy the city’s problems. New codes require new projects to reduce the amount of impervious surface.

Local leaders are starting to use many different kinds of incentives to encourage developers to build in environmentally friendly ways.

In Whitpain Township, large office complexes can now have smaller parking spaces, provide the saved space is a green area, said panelist James Blanch, a civil engineer who works for the township.

“The developer saves money on paving material,” Blanch explained, while there is less water run-off.

Panelist Sandy Wiggins, founder of Consilience, LLC – a national consulting and real estate development firm with a mission to build in environmentally conscious ways – suggested municipalities fast-track developments that employ good water management. “Time is money,” he said. “If you can knock six months of the pre-development time line, that’s a lot of money to a developer.”

Evelyn McKnight, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s water resource director, said that in addition to such carrots, communities also need to investigate a powerful stick: Charging fees based on the amount of runoff a development produces.

Philadelphia is now investigating that very stick.

Despite all the scary money talk, Newman wanted everyone to know that there are inexpensive ways to make a difference. “I was driving around with a stormwater management planner in a municipality a couple of weeks ago, and all of the water from every roof went into the ground … it was connected to a sewer. And all of the driveways were connected to the road. I remember one house with a large, flat lawn, but still, the roof just drained into a pipe. Just disconnecting everything would be very helpful.”

Susan Harris, watershed specialist for the Montgomery County Conservation District, said low impact developers can actually save money in the long run. For example, leaving existing vegetation in place where possible helps retain storm water – and it also costs less than stripping everything off the land.

While the panelists all said governments must take action, they concurred that the consumers who buy homes or lease office space have more sway with developers.

“What this country comes down to is voters, residents, people who buy goods and products,” said Janet Bowers, executive director of the Chester County Water Resources Authority.

“Do you believe that both residents and developers are beginning to realize that green infrastructure enhances property values?” moderator Barry Davis, chief deputy in the city of Philadelphia solicitor’s office asked.

Wiggins said that was happening in a big way in some places around the country.

“Around here, we’re not there yet,” he said. “It’s still an obstacle.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.