Will people feed their pets lab-grown meat?

Lab-grown meat for dogs and cats might be on the market before lab-grown meat for humans.

Listen 08:55

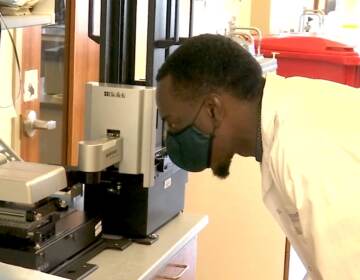

Scientist Shannon Falconer co-founded a company that's growing meat for pet food in a lab. (Image courtesy of Because Animals)

Shannon Falconer loves animals and she didn’t like the idea that they were being killed to feed her pets.

She has two dogs, a Labrador mix called Gaia and a tiny Chihuahua mix named Trots.

“As a kid, I grew up with three dogs and three cats,” Falconer said. “We had a lot of foster pets coming into our house as well, and I was an only child, so my siblings were my pets.”

Falconer stopped eating meat more than 20 years ago, but that’s not an option for cats and dogs. She became a scientist and got a doctorate studying antibiotics. Then she talked to Pat Brown, a former professor of biochemistry at Stanford University.

“This man who is an M.D. Ph.D., who had a career that he loved, and he left it all to basically create a veggie burger,” Falconer said.

Brown founded Impossible Foods, which is behind Burger King’s new plant-based Whopper. That made headlines nationwide.

The next frontier in replicating meat is to grow it in a lab, instead of making a meat substitute with plant material.

Falconer was inspired by Brown, so she decided to build on these ideas — with pet food.

She co-founded a company called Because Animals three years ago. It’s developed a dog cookie made from nutritional yeast, a popular cheese substitute in vegan food.

The company’s next product is the one Falconer dreamed about: a meat product that doesn’t involve killing an animal. It’s made in a lab from animal cells.

Scientists grow mouse muscle cells in a nutrient-rich broth in a petri dish, then harvest the tissue to put into a cat treat. It looks like a little brown meatball.

Falconer points out that bacteria would also like this nutrient-rich broth, but it is very easy to identify any potential contaminants and act against them.

Falconer and her colleagues have already fed a prototype of the mouse meat to a few cats. The next step is to make the process cheaper and more efficient, so the company can grow and sell on a larger scale.

For context, the people who made the first lab-grown burger for humans said one of those would cost $50.

Falconer acknowledged that feeding pets meat from a petri dish might sound a little strange at first.

“I know people sort of think it’s some sort of Frankenstein thing,” she said. “There is not a doubt in my mind that this will not be the way of the future.”

At a dog park near Philadelphia, I asked people who were walking their dogs: Would they feed their dog meat that was grown in a lab?

Reactions ranged from “ … this dog will literally eat anything,” to “humans have moved more towards natural food, and so it would be hard to accept [and] then moving towards petri dish-created food for our dogs.”

Falconer said that she didn’t see any of the reactions as negative, and that she would be surprised if nobody was hesitant at first. Now, as to the person who wondered whether lab-grown meat is natural, Falconer said that’s an interesting question.

“There’s nothing natural about pet food as it exists right now, nothing,” Falconer said. “The only reason why we feed cats chicken or beef or fish is because … it’s byproduct. In the wild, cats eat mice, small birds, and insects.”

She noted that the most common food allergens for cats and dogs are, in fact, beef and dairy products.

“For us, by creating a food, a mouse tissue for cats, this is arguably much more natural than … beef,” Falconer said. “A cat, a feral cat is never going to take down a cow in the wild.”

Animal-welfare scientists, Andrew Knight and Madelaine Leitsberger, went a little further in a 2016 journal article about vegetarian diets for cats and dogs.

They wrote that pet owners “frequently microchip, vaccinate, de-worm, de-flea and de-sex their animal companions, and confine them indoors at night … Clearly, such owners are willing to depart quite radically from ‘naturalness’ when they believe it may protect the health and welfare of their pets.”

There are, of course, those who want to feed their pets meat from a slaughtered animal. There is a thriving business around marketing cat and dog food that would be fit for a wolf or a tiger, with packaging that features the gleaming eyes of hungry carnivores. But animal scientist Ryan Yamka said wolves will actually happily eat berries and figs.

“Wolves like dogs or any others, they don’t necessarily seek out meat, they’re opportunistic feeders; and so they also forage.”

Yamka is an adviser to Bond Pet Foods, another startup that wants to take animals out of the pet food supply chain, though he’s not paid for it. He said wolves and dogs and cats actually don’t care about what kind of meat they’re eating; it’s just a vehicle for nutrients.

“They’re not focused on protein, they’re actually focused on amino acids,” he said. “In the case of a dog, if I could supply the proper amount of amino acids and it’s digestible and bio-available to that dog, that dog’s body doesn’t care if it came from soy or chicken, or it came from a cultured protein or algae or duckweed or crickets.”

Consumer attitudes aside, lab-grown meat could become a reality for pets much more quickly than for humans.

Big players are paying attention and getting involved. Purina, the second largest pet food company in the world, gave Bond Pet Foods, the company Yamka consults for, a $10,000 innovation prize.

And chances are, pets won’t even notice the change.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.