Deepfakes: What are they and should we be worried?

Machine learning is democratizing special effects — and that might be a bad thing.

Listen 13:04

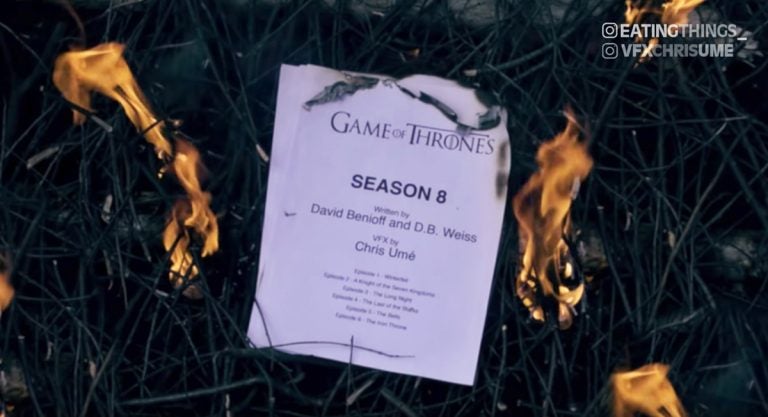

A screen grab from the viral deepfake that Chris Ume and his friends created spoofing the final season of "Game of Thrones." (Image courtesy of Chris Ume)

A few months ago, a new video started making the rounds on YouTube, entitled, “BREAKING: JON SNOW FINALLY APOLOGIZED FOR SEASON 8.”

It opens on a grim “Game of Thrones” scene from Season 8. Jon Snow, a character in the show, is giving a speech to mourn the fallen in the wake of a major battle. But instead of talking about the soldiers’ sacrifice, he says something else.

“It’s time for some apologies,” he says, looking around at the solemn crowd. “I’m sorry we wasted your time. I’m sorry we didn’t learn anything from the ending of `Lost.’”

As the camera pans around to the grief-stricken faces of the series’ most beloved characters, the apology continues.

“I’m sorry we wrote this in like six days or something,” Jon Snow says. “Now … let us burn the script of Season 8, and just forget it forever.”

And with that, we see the script of season 8 go up in flames.

With more than 2 million views, and over 2,000 comments, the video clearly struck a chord with “Game of Thrones” fans — which is understandable, given the near-universal outrage at how the show’s final season unfolded.

But there’s arguably another reason the video made such a splash — its special effects. Jon Snow’s apology is clearly fake, yet it looks and sounds real.

According to the video’s creator, special-effects artist Chris Ume, that’s thanks to the power of deepfakes.

There’s a relatively simple formula to creating deepfakes, Ume said:

- First, you download the software (most people use either Deepfacelab or Faceswap).

- Next, you gather photos and/or video of the person you’re trying to deepfake, preferably from as many different angles as possible.

- Then you feed that media into the software, giving it a week or two to “learn” how that person’s face and mannerisms work, all the way down, Ume says, to “the sparkle in [someone’s] eye.”

“If the quality of your source footage is good, it should learn this,” Ume said. “And this [is] done automatically.”

The final step depends on what kind of deepfake you’re creating. You can simply switch out someone’s face for someone else’s; change what they’re saying, and adjust their lips to match; or go full-on puppet master and essentially use the deepfaked person’s appearance as a costume for a lookalike.

And voila — you’ve got a video of someone saying and doing something they never said or did.

Special-effects artists like Ume, both professional and DIY, are excited about the potential that deepfakes bring. But others are worried. They say the proliferation of this new technology poses threats, both to individuals who could find themselves targeted for nonconsensual videos, and to our larger system as a whole.

What makes deepfake technology special?

According to digital forensics expert Hany Farid, who teaches at the University of California at Berkeley, the technology isn’t completely new. Versions of it have been used for years in academic circles, and to create special effects in Hollywood. What’s new, Farid says, is the democratization of the technology — and its ability to continually improve itself.

“I think what is dramatic about this is that the machines are essentially doing all the heavy lifting,” Farid said. “The way it’s actually generated is there’s two computer algorithms — technically they’re called deep neural networks — and one is a synthesizer and one is a detector. And the synthesizer creates the fake content and asks its counterpart, the detector, whether it’s real or not, and they work together in a very tight loop.”

As these two algorithms work together, they learn from each other — which means they’re getting better and better.

“There’s more and more data that — machines themselves generate data, which then comes back into the system. And I think that’s part of the reason why we’re seeing this very rapid development in the technology.”

Why are people worried about deepfakes, and what threats do they pose?

“Fake news, fake images, and fake video is not new, but the sophistication and, again, the democratization of access is a worrisome trend that we are seeing,” Farid said.

It’s led some experts and critics to call deepfakes a threat to democracy — or at least, to the shared objective reality that’s necessary for democracy to function.

“I’m worried about all kinds of things,” Farid said. “I’m worried about the video of a candidate for high office being released 24 hours before an election — and before anybody figures out it’s fake, we’ve had a manipulation of our democracy. I’m worried about national security issues … These genuinely worry me.”

How did deepfake technology become so widespread?

The democratization of deepfakes — along with the name — started with an anonymous Reddit user named “deepfakes,” who in 2017 started distributing fake celebrity porn. The user also began distributing the technology to create the deepfakes.

“The deepfake algorithm that was developed by this particular user on Reddit turns out to be a very robust and reliable, and, relatively speaking, simple technology,” said Siwei Lyu, an expert in digital-media forensics who teaches at the State University of New York at Albany.

“So he actually published his code as open-source software, and subsequently there were quite a few other implementations of the same algorithm. And everybody [who has an] internet connection, knows a little bit about computer programming and machine learning will be able to run this code and start making fake videos.”

What risks do deepfakes pose to individuals?

Noelle Martin was a college student in Australia when she discovered that her social media photos had been stolen and posted — along with her name and personal information — on multiple porn websites. That kicked off a years-long fight to get her photos taken down.

“I mean, it shattered everything,” Martin said. “Like I just had this cloud over my head for, you know, six, seven years, and I wanted essentially — you know, I did not want to live for a lot of my adult life.”

Martin became a well-known activist against image-based abuse and nonconsensual pornography — a fact that she suspects was connected to the release of deepfake pornography videos featuring her face.

“It was, in my opinion, something that was used as an attempt to silence me and intimidate me,” Martin said. “It angered me that they had the audacity to do that and to try and, you know, silence and weaponize this technology or this form of abuse as a means to kind of control and manipulate women.”

The technology’s rapid development is putting more and more women at risk, she said.

“People can use one photo to create these videos — they don’t need hours of footage of someone,” she said. “That’s the scary part … that as technology advances and becomes better over time, then these videos are going to look so realistic. They are already starting to look extremely realistic to the point where it’s really difficult to detect what is real and what’s fake.”

How can deepfakes be stopped?

As the technology advances, researchers around the world are looking for ways of identifying deepfakes.

Among those researchers is Siwei Lyu, the digital-forensics expert at SUNY Albany, who along with some colleagues came up with a widely publicized detection technique — to which deepfake creators quickly adapted.

“I think in the long run, it’s just kind of like a cat-and-mouse game,” Lyu said. “You know, it’s always going to be kind of a competition between the detection side and the synthesis side. So both sides will continue improving.”

Hany Farid, who’s also working on detection techniques, agreed.

“There absolutely will come a time where the generation of deepfakes will defeat our forensic techniques,” Farid said. “Our hope is that that takes not weeks or months, but years. And in the meantime, we will develop new techniques.”

The hope is that each new tactic will buy them enough time to come up with another one — and weed out the deepfake creators who aren’t savvy enough to bypass them.

“So the game here that we are playing is not eliminate the threat,” Farid said. “It’s not eliminate the ability to create deepfakes, but it’s make it harder, more time-consuming and more risky, and take it out of the hands of the average person and put it back into the hands of a relatively small number of people.”

Others are arguing for legislative reforms that would make deepfake creators legally responsible for disseminating libelous videos, including deepfake porn. But many of those efforts are currently stalled.

Deepfake artist Chris Ume argues for a different kind of strategy.

“People just have to learn to be more critical — that’s the point,” he said. “They don’t have to be scared of deepfakes, because it probably existed even before you heard the word ‘deepfake.’ You just didn’t know it. At least now, you know it exists, and you know you shouldn’t believe what you see.”

What’s the bigger picture of deepfakes’ impact?

Farid said the threat deepfakes pose goes beyond the dissemination of fake content.

“What happens in the world if anything can be fake?” he asked. “Nothing is real. If more than half of the content that we see online is fake, how are we going to distinguish the real from the not real?”

“And I think that’s what’s more worrisome, is that the ecosystem is going to become so poisoned that nobody’s going to be able to believe anything they see, hear, or read online.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.