What we learned about disaster response from 9/11

Listen Photo via ShutterStock)" title="9/11 memorial for pulse" width="640" height="360" fetchpriority="high" />

Photo via ShutterStock)" title="9/11 memorial for pulse" width="640" height="360" fetchpriority="high" />

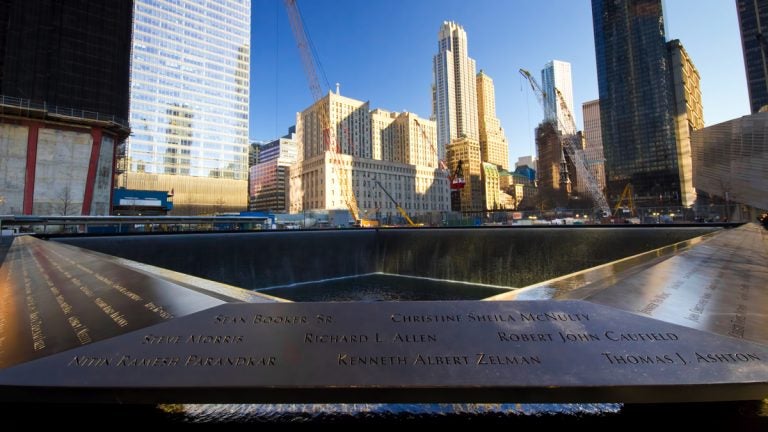

(<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-106467170/stock-photo-new-york-city-feb-nyc-s-memorial-at-world-trade-center-ground-zero-seen-on-feb.html?src=DHw5ckIRt8RNXMYahldmLQ-1-13">Photo</a> via ShutterStock)

Survivors and researchers have been working together to better understand human responses in the midst of major emergencies.

Many people are still dealing with the physical and emotional impact of 9/11. Over time, though, survivors and researchers have also been homing in on the events of that day, to better understand human responses in the midst of major emergencies and to learn what factors contributed to the decisions and course of action that day.

Today, the site of what would have been the two towers consists of a memorial plaza, adjacent to the newly constructed Freedom Tower. Surrounding the perimeters of what would have been the towers, are waist-level walls. Engraved on them are the many names of people who died on September 11, 2001. On the other side, in the footprint of where the actual towers once stood, is a waterfall, nearly an acre in size, descending down the sides. It forms a pool. The water drops down yet again into a smaller square that appears to have no bottom.

On a recent weekend, hundreds of people line the walls, looking up, leaning in.

One survivor’s experience

Peter Miller knows what once stood in those reflective pools very well.

“Most of my career I was on the 65th floor, 63rd, 64th floor, but right in that area of the north tower,” he says.

Miller had been working inside the World Trade Center for the Port Authority since the ’80s. He’s soft spoken and has a neatly trimmed white beard. Sitting inside his apartment uptown, he recalls some of the details of that early fall day.

“I was settled into my computer,” he says. “My office was on the north side with windows looking out onto the George Washington Bridge, the Empire State Building. And it was just a beautiful day.”

Crystal clear. He had been on vacation and come in to the office early to catch up.

At 8:46 a.m., the plane struck the building. He described hearing what sounded like a plane accelerating at takeoff. He felt a huge jolt. He thought the floor would cave in. It didn’t.

“I remember people on our side of the floor who got up after the impact, and said, ‘What was that?’ They didn’t hear the plane, so the senses select which one works, I guess.”

He says he and a colleague went toward the center, gathering with others. He turned back at one point for his backpack. Another coworker wanted to stay at her desk.

“She said, ‘I’m waiting for instructions. Aren’t we all supposed to wait for instructions? I’m waiting for instructions.'”

Through a series of decisions and dynamics that played out next, Miller, his coworker and thousands of others eventually got out.

In the years since 9/11 many have reviewed these critical evacuation moments, in hopes of improving response efforts in the future. It didn’t happen right away, but Miller and others began revisiting the details of what happened in the critical moments of that day – what went well during that evacuation, what didn’t.

“I had this more abstract sense of why should I survive when so many people died?'” he recalls. “What can I learn from this?”

A survivors group formed.

Searching for insights

Robyn Gershon, a public health disaster researcher at Columbia University at the time, also set out to find answers.

“We wound up doing the single largest high rise evacuation study up to that point that had ever been conducted,” she says.

A few months after the attack, Gershon began interviewing Miller and others, analyzing the details of that day. She says people’s responses paint a complex picture. Her research took years to complete.

The value of training, of any kind

She found the evacuation, in many ways, was a success. The buildings weren’t full that day, and most people who were below the floors of the crash made it out. Even so, at least 25 people in her study got out at the very last minute.

“We found that, on average, people delayed six minutes from the time of the first impact of either building before they started their egress out of the building,” she says.

Gershon says once the plane hit, many were searching for information when there wasn’t a whole lot. The p.a. system was down in the north tower, for example. And she learned that many, by no fault of their own, lacked important knowledge about emergency preparedness for the building.

“When I saw the data staring right at me, I was shocked to find out that so few had any kind of training, had ever even been in the lobby to get the training from the fire safety director at the time,” she says. “I was shocked.”

Some didn’t know about the different stairwells. That’s why she says even basic knowledge of a building layout in advance is critical in preparation for major disasters.

Amanda Ripley, meanwhile, a journalist who covered 9/11 and other major disasters had also spent a lot time interviewing survivors. A few years after the attack, she visited the group Miller was involved in.

“I went to a meeting of the World Trade Center Survivors Network with a totally inaccurate idea in my head of what it would be like,” she says. “I was bracing for another exchange of grief, but what actually happened was they were sharing lessons learned and strategies and they wanted very much to share.”

Exploring why people delay

This made Ripley even more curious about those moments, those initial delays. She began researching other disasters, discovering patterns she hadn’t expected in human behavior. Ripley says even amid a major, incomprehensible situation, people may first enter a phase of denial. They may even freeze up.

“It’s not that they’re idiots. This is a normal human reaction,” she says. “Given uncertain information, your brain will search for patterns, explanations that make sense.”

She recalls the story of another woman who was in the tower.

“She remembers grabbing onto her desk and lifting feet off the floor and shouting ‘what is happening?’ But one of interesting things that happened after this, and this was something that many survivors talk about, is that what she wanted someone to shout back, what she wanted with every fiber of her being was someone to shout back, ‘Nothing! Don’t be crazy. Go back to work.'”

What also happens, says Robyn Gershon, is something she has noticed in other disasters.

“There’s some phenomenon that’s referred to as the emergent norm,” says Gershon. “Someone steps up to the plate to take charge of the group.”

It’s often a person with previous emergency training, maybe a volunteer fireman or a member of the military, who doesn’t freeze up. In the case of Peter Miller, who was in the North Tower on 9/11, he had some familiarity with the stairwells and evacuating the World Trade Center, when a bomb went off in the basement in 1993.

“What we learned in ’93 was that there are no instructions,” he says. “You can’t depend on that.”

The building’s fire safety marshalls had always drilled in the importance of instructions. Depending on the situation, going down a stairwell may not always be the best option.

But 9/11 was different, Miller recalls. And he knew a plane had hit this time. So he says he and a colleague didn’t wait for orders. They consulted with one another about what to do. A different kind of “down and out” instinct kicked in and the group decided to get out. He recalls helping inform people that a plane had hit, to enforce the need to leave the floor.

Yet the weight of what was happening, he recalls, hadn’t sunk in.

“Our experience with ’93 gave us a false sense of confidence,” he points out.

Miller didn’t feel like he was in a huge rush to get out because he didn’t realize the building would collapse. And in ’93, there was more time. And evacuating down certain stairs quickly during ’93, he recalls, led to more smoke exposure.

Ripley says while limited, inconsistent information based on past experiences can have weaknesses, it can also work in people’s favor and help them reach safety.

“The good side of that is it is reassuring to you, and prevents from freezing all together,” she says. “Because the denial cushions the blow and the realization of what’s happening.”

For some, realizing the magnitude of a horrific event can dull the senses, leading to a slower response, a loss of hearing or even vision.

Debunking the panic myth

Ripley was surprised to learn about another aspect that she heard recounted of what happened in those stairwells.

“We naturally assume that in a disaster people will behave the way that they behave in rushhour on the freeway, which is to say not very nicely. They’re under stress and sometimes people behave badly when they’re frightened,” she says. “But in fact, it’s not really in your survival interest. When you ask survivors what it’s like in stairwells, it’s not the answer we might expect. What they tend to say, not always, but typically is that it was very quiet and calm. People were very orderly.”

Miller recalls when one or two people did panic, others helped calm them. People are social, they often gravitate toward one another.

“Everyone expects the entire group of victims to run screaming and trample each other and that’s simply not the case,” says Miller.

Gershon says, and what matches recounts of other major disasters, unless there’s competition for something like an exit, people don’t tend to panic. They help each other.

“You know, we’re social animals. We want to be with others when there’s anything that’s unusual or there’s some kind of threat to us,” she says, adding that the larger the group amid an uncertain situation, the greater the chances people could take longer to make a decision and take action.

Big picture takeaways, 14 years later

For Gershon, one of her biggest takeaways from her research is the role of preparedness, even at the most elementary level of knowing where the exits are in a space. And 9/11 highlighted the need to reassess protocols, so people know who to turn to and how to respond in their buildings, instead of spending too much time figuring out what to do.

After 9/11 the city worked to update its building codes for the first time in three decades.

“I think the fire code change was enormous, really enormous,” says Gershon. “All of a sudden it made that director of these high rises have a much more important role in protecting the health and well being of people in those buildings.”

The updates include expanding the fire safety director role of a building into that of an emergency action plan director. That included more training for directors and occupants, not just for fires, but for other types of emergencies like chemical attacks, natural disasters or other instances of violence.

For Amanda Ripley, she says a big takeaway for her is that at the end of the day, people’s most important tools and allies when it comes to major disasters will likely be each other…neighbors and coworkers.

“This is important,” she says. “These are my first responders, and I am theirs.”

As for Peter Miller, he hopes these and other lessons will resonate with others.

“It’s to remember what happened, and to be respectful and sad to those it happened to, but also to try and find ways that we can be stronger and actually better as a result of it,” says Miller.

Over the years, his group has connected with survivors from other emergencies, such as the Boston Bombing and the Oklahoma City bombing. They provided input to other disaster planning guides, most recently in New Zealand.

Back to Ground Zero

Memories of 9/11 are still raw for Miller and his family. He recalls people helping each other down the stairs that day. But as they descended, his own adrenaline wore off. He become disconnected and less helpful. Other responders guided him to safety. Eventually, he made his way back to his apartment several hours later, to his wife Cathy Miller.

“We didn’t know where Peter was – I can’t look at him – alive until two in the afternoon so that was tough,” she says, sitting across from him at their table. “The not knowing was very hard.”

“In many ways she suffered more profoundly than I did that day,” Miller replies.

“It was on the one hand hard to believe it ever happened, and on the other hand it’s very immediate, and he was amazing,” she adds.

On the 9/11 anniversary, Miller often meets up with other survivors for an annual lunch and memorial service downtown. He says he has been back to Ground Zero a couple times. His and other survivor’s stories can be heard inside the new Memorial Museum, and some from his group have helped lead tours of the site.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.