What the Medicaid expansion means for those ‘in the gap’

Listen

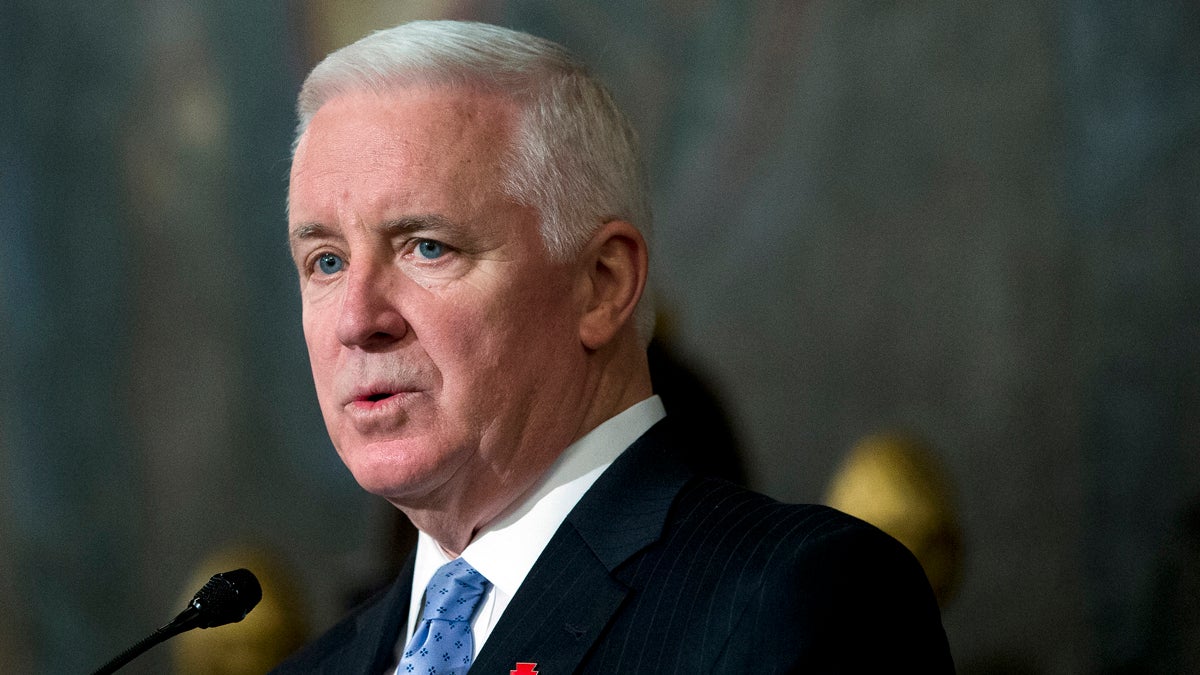

(AP Photo/Matt Rourke

Last week, the Corbett administration announced a Medicaid-alternative agreement with the federal government that would allow more people into Pennsylvania’s Medicaid program.

The debate over the Medicaid expansion in Pennsylvania has largely centered around people “in the gap.”

Today, when people “in the gap” go to the Affordable Care Act marketplace to shop, they’re often surprised to learn they don’t qualify for discounts and tax breaks.

David Coleman from Philadelphia said he was eager to sign up.

“I found out I made too much for Medicaid and that I didn’t make enough to get the benefits of Obamacare,” Coleman said.

Under the federal health law, single people who earn around $12,000 a year were supposed to get their coverage through an expanded Medicaid program. But in Pennsylvania, initially, that expansion didn’t happen.

Last week, the Corbett administration announced a Medicaid-alternative agreement with the federal government. Pennsylvania will get billions of federal dollars in coming years. In exchange, the state is welcoming more people into its Medicaid program.

Some opponents wanted to reserve Medicaid for the most vulnerable people. They argued that it’s too costly to allow “able-bodied, childless adults” in to the program. But starting next year, people “in the gap” can enroll in the Corbett-designed Medicaid alternative.

Corbett’s Medicaid expansion alternative is getting mixed reviews.

In an analysis for Forbes, analysts from the conservative think tank the Foundation for Government Accountability said: “Gov. Tom Corbett (R-PA) is the latest Republican to be flamboozled, having fallen into this trap with his Healthy PA plan.”

Health economist Janet Weiner has questions too, but said the plan may be good news for federally qualified health centers across the state.

“Their bottom line should be helped tremendously,” said Weiner, with the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute.

Health clinics already care for many patients “in the gap” with no insurance.

“Many of these people are already being seen, not in a coordinated systematic way but they are going to the health centers anyway,” Weiner said.

Adults between ages 21 and 64 with incomes through 133 percent of poverty level will be eligible for the new coverage. Pennsylvania created a program for the newly eligible population that is different by design than traditional Medicaid, said Leesa Allen, executive Medicaid director at the Department of Public Welfare.

The idea is to get low-wage earners used to the way health insurance works in the private sector, she said.

“We were really looking for this to be a pathway to employer-sponsored coverage; we wanted it to look and feel like employer-sponsored coverage,” Allen said.

In 2016, some participants in Corbett’s alternative Medicaid plan will pay premiums. People will chip in $20 to $25 a month toward their coverage but could get a discount on that bill if they follow through with some healthy behaviors such as getting a yearly check-up.

“Our data has shown when folks lead healthier lives that overall health care spending goes down,” Allen said.

Work-search and health coverage

In the official agreement, the federal government said “no” to one of Corbett’s more controversial proposals. He wanted to link job-search requirements to health coverage. Using state dollars, Pennsylvania is moving forward anyway with a program to encourage employment. Allen says newly eligible Medicaid participants will get a career coach and help looking for work, such as resume writing and interview skills.

“We’ve seen lots of connections where folks who were working have had improved health just from the perspective of being able to feel some self worth in themselves,” Allen said.

In coming years, Medicaid-alternative participants will pay less for their insurance if they participate in work-search activities, Allen said.

“That is our goal, is to have them have a reduction in their premium costs in year two,” she said.

By email this week, Aaron Albright, a spokesman with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services clarified the federal government’s position on Pennsylvania’s “Encouraging Employment” program: “Health coverage or benefits will not be affected by this state initiative.”

A new bureaucracy

Collecting premiums from enrollees is a departure from the way the Department of Welfare manages Medicaid now, said economist Genevieve Kenney, co-director in the Health Policy Center of the left-leaning Urban Institute.

“What it means is that within the agency, you are going to have to develop a unit that’s dedicated to tracking receipt of premiums,” she said. That includes canceling coverage when people fail to pay their premiums on time–and re-enrolling them when they are ready to return to the program.

Pennsylvania is setting up a parallel system for its newly eligible enrollees, and Kenney said the bureaucracy of tracking relatively small premium payments could be costly, especially if calculations are attached to monitoring patient health behaviors.

Also, she added, there’s good evidence that asking very low-income people to pay a monthly bill–before they use their health insurance–discourages some people from buying coverage at all.

“It can get pretty complicated,” Kenney said. “It could end up being a net cost to the state and not generate saving that may be anticipated.”

Enrollment for the Medicaid alternative begins in December to gain coverage in January 2015.

The nearly 400,000 newly eligible people won’t try to sign up on day one, but analysts are trying to figure out if Pennsylvania’s health system is ready to absorb the demand.

Health policy watcher Janet Weiner said other expansion states have not experienced widespread primary-care shortages. But some Pennsylvania counties are already designated primary-care shortage areas by the federal Health Resource and Services Administration.

Kenney said Pennsylvania would need to rely even more heavily on mid-level health care providers such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

Bus driver David Coleman, one of the newly eligible people in Philadelphia, said for him, the change means health and financial “security.”

Coleman says chest pains landed him in the emergency room in 2013, and he ended up with an $8,000 medical bill. He doesn’t have a primary care doctor. After his trip to the E.R., he tried to book a follow-up appointment at a local clinic and he says the first available spot was three or four months away.

About 168,000 people who are currently in Pennsylvania’s traditional Medicaid program could transfer over to the alternative program.

Medicaid director Leesa Allen said 80,000 potential transfers are in the state’s general assistance population. Another 88,000 are in the SelectPlan for Women program, which provides family planning care.

Health care for the state’s general assistance program is paid for with mostly state-level dollars today. The Medicaid-alternative plan will be 100 percent federally funded through 2016.

“Once you get beyond the ideology of not expanding Medicaid, this is really a dollars and sense issue, and I think Pennsylvania is recognizing that,” Weiner said.

Still to come are the details of a plan to cut back the health benefits package for Pennsylvania’s traditional Medicaid program.

Health reporter Elana Gordon contributed to this report.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.