Vivid dreams and their role in waking life

Many people practice remembering their dreams to help with clarity, creativity, or problem solving.

Listen 9:10

Many people practice remembering their dreams. What's the use in that? (Image courtesy of val.pearl/Flickr)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

A lot of us experience a memory lapse every day — when we first wake up and our dreams slip away from us.

But there are people who remember their dreams often, and in striking detail. Some work hard to cultivate this skill because they believe dreams are useful for waking life.

Is that true? And what separates someone who always remembers dreams from someone who never does?

Shady Rose, an artist in Washington, D.C., falls in the camp of people who remember their dreams.

On a recent Sunday morning, Rose had just woken up and a dream from the previous night was still fresh on their mind.

The dream started in media res, Rose recounted. “I woke up in a hole in this salt flat desert, with this man looking for me, trying to take me back to the town or the city where I was wanted for something, ” they said.

As they’re talking, Rose gets a far-off look in their eyes, like they’re summoning the experience.

“The salt was really white, and the sky was really blue,” they said. “There was sort of like a hazy mirage around the horizon, everywhere I looked. I can feel the sweat on my back, even though it’s very cold in the dream.”

This sort of detailed, sensory recall is common for Rose. For as long as they can remember, they’ve had an extremely rich dream world. They’ve kept a journal since they were a kid, and they try to record their dreams as often as they can. A lot of their dreams sound like post-apocalyptic movies.

There was one recurring dream series, for instance, in which the world had ended and Rose was part of a group trying to preserve human knowledge. In different dreams, they had to perform different missions, like going to the seed bank or saving books from the Library of Congress. (If you’re wondering, Rose succeeded in saving the books. “They’re in a vault very deep underground, in a ruined Washington, D.C.,” they said.)

Rose said they feel like they live two lives, of equal proportion: a dream life and a waking life. They’re the same person in both worlds … with maybe some tweaks. “For example, in my dreams, I know how to fight really well,” they joked.

But the events that transpire in Rose’s dreams often provide just as much insight for them as events from waking life.

“When I’m dreaming, I have the opportunity to test my view of myself — to put myself in so many different outrageous circumstances and really live through them, and almost simulate ways to interrogate my beliefs,” they said.

“The only thing I ever strive to do, whether awake or dreaming, is to be my best self,” they added. “To be kind, to find the truth, to act fearlessly when I can.”

High vs. low dream recallers

Maybe you’re questioning whether anyone can really remember their dreams in this much detail. Rose offered a few speculations about why they might remember their dreams so vividly.

For one, they were raised in a deeply mystic religion from Ghana, called the Akan, or Akom, tradition. Rose believes their spiritual upbringing made them more open to the surreal, or more willing to question perceptions of reality.

“I was taught from a very young age to respect and think about dreams, but also daydreams, and errant thoughts, and letting your mind wander,” they said.

They also suspect their sharp dream recall has to do with how their mind works generally. Even in waking life, they’re honed into little details and sensory experiences.

“My brain gets in the habit of sort of regenerating detail,” they said. “The room I’m in right now, if I were to close my eyes, I could pretty much draw everything in it. And I think that sort of transforms into, in my dreams, generating that much detail.”

Some people, like Rose, remember their dreams like they’re immersive blockbusters. Others remember just a few fuzzy details, or nothing at all. Why is that?

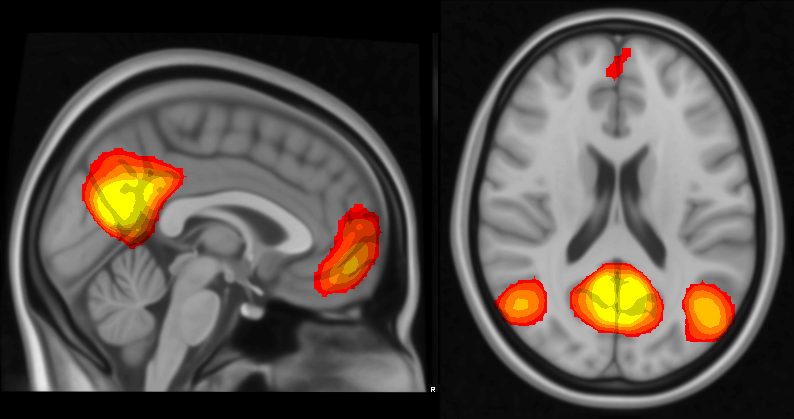

Raphael Vallat, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, looked into this question. Using fMRI and PET scans, he compared the brain activity of high dream recallers — people who remember their dreams every day — with low recallers, who never remember their dreams.

“One thing that we consistently found is that high dream recallers typically have more activity in one specific brain network,” Vallat said.

It’s called the default mode network, and it was only discovered in 2001. The default mode network helps us view and make sense of ourselves. For example, it facilitates episodic memory, or the long-term recollection of specific events and experiences. Your memories of your first day of school, your first kiss, or a powerful conversation you had with a friend are all episodic memories.

The default mode network is also active when your mind is wandering — when you’re in a dreamlike state.

“Say you are commuting, you’re on the train, you have nothing to do, you’re just looking at the landscape out the window, and completely lost in your thoughts,” Vallat said. “That’s when the default mode network is very active.”

His team found the default mode network was more active in high dream recallers, not just when they were asleep, but also when they were awake. “For us, that means that there are some fundamental differences in memory processes between these two groups,” he said.

These findings add to a growing body of research that suggests dreams play a role in memory consolidation.

“You are actively reprocessing and filtering memories, in order to optimize which ones you need to remember, which ones you can forget,” Vallat said. “For example, is it relevant for you to remember where you parked your car two weeks ago? Probably not.”

Scientists know that daydreaming is important in memory consolidation. When you let your mind wander, “you will typically reprocess some of the memories, some of the experiences that you experienced maybe the day before, maybe one hour before, or even memories from years ago,” Vallat said.

The thought is, this process is also happening when you’re dreaming in sleep — but to an even stronger extent.

“Just because the brain state is so different … and you have no inputs because you are asleep, we think that this reprocessing of memories is much, much more efficient when you’re actively dreaming than when you are just mind wandering,” Vallat said. “But this is very new, so we don’t have all the answers.”

You don’t necessarily need to recall your dreams upon waking, however, for them to be effective. “Probably you don’t need to remember your dreams for them to actually be doing something for your emotional regulation, memory consolidation, and all,” Vallat said.

Still, tons of people are captivated by their dreams, and really want to remember them. What’s the use in that?

A window into our inner lives

Some believe that dreams are useful for emotional processing and reflection.

“Attention to dreams isn’t necessarily about focusing on the dream world — it’s about getting in touch with life,” said Mark Dean, a psychotherapist in Philadelphia.

Dean practices Jungian analysis, which is based on the ideas of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. He also runs a weekly dream group in Philadelphia.

“I really want to go to the dream as a source of wisdom that knows something I don’t,” Dean said. He believes dreams are messages from our unconscious, pointing us toward things to pay attention to, or make connections between, in waking life.

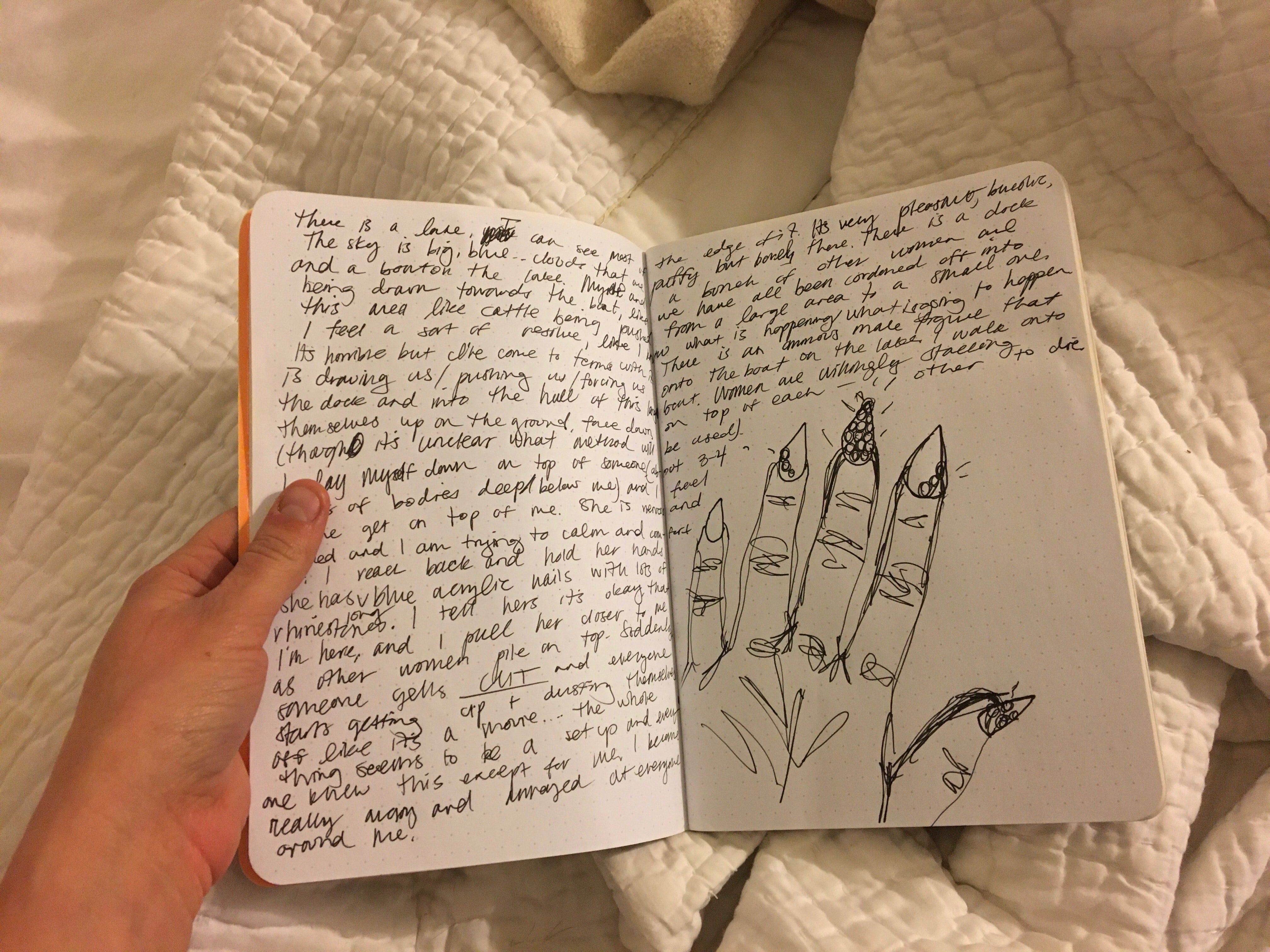

During a dream analysis between Dean and a former dream group participant named Sam — we’re not publishing her last name, to protect the privacy of her personal dream — she said the dream’s setting was a lake.

“You can see most of it. The sky’s pretty big,” she said. In the dream, she’s in a dangerous situation on a boat with a bunch of people. And she helps this one particular woman.

The woman has “blue acrylic nails with a lot of diamonds and details on them,” Sam recalled.

“Could you say a little bit more about the woman with the fingernails? What comes up for you around that?” Dean asked.

“Yeah … there are moments when I want to have acrylic nails or something like that,” Sam said. “And then, also many moments where that feels like that doesn’t actually fit into my life, or who I am.”

Here, Dean says, the woman with the acrylics maybe represents Sam’s relationship with her own femininity. In the dream, she’s kind of reconciling with that part of herself.

“As a young person, I definitely identified as a tomboy or something along those lines,” she continued. “But also, yeah, having moments of deeply wanting that sort of femininity and being able to perform a sort of feminineness is… powerful.”

Dean believes this happens a lot in dreams — we think we’re interacting with some other person or thing, but we’re actually interacting with what he calls shadow aspects of ourselves: “an aspect of the dreamer that the dreamer doesn’t fully identify with, and yet somehow or another, is lurking in there,” he said.

The mind is able to produce a whole world

When you talk about dream analysis with academic researchers, they’re reluctant to say anything about it. It’s hard to back with scientific evidence.

Michael Schredl is a dream researcher at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany. He doesn’t necessarily believe in Jungian analysis, but he agrees with Dean on this: “Dreams are very clearly related to your waking life experience,” Schredl said.

Schredl has been recording his dreams for 36 years. “Now, I think I have 15,500 dreams, or something like that,” he said.

Dreams, he said, often take waking life and exaggerate, or dramatize, or turn into metaphor. They can be “very helpful for us to understand what’s really important,” he said.

For instance, “say you are avoiding something in your waking life,” Schredl said. “Then you might have the dream of a monster that’s chasing you. The main focus is that you have anxiety, or panic, and you are not confronting anything. You are just running away.”

Dreams also show us what the mind is capable of.

“I think it’s still underappreciated that, in dreams, the mind is able to produce a whole world without any external input,” Schredl said.

Tapping into these dream worlds, he added, can be an impetus for creativity and art. “I’m still astonished about the creative function, the creative mode, of dreams,” he said.

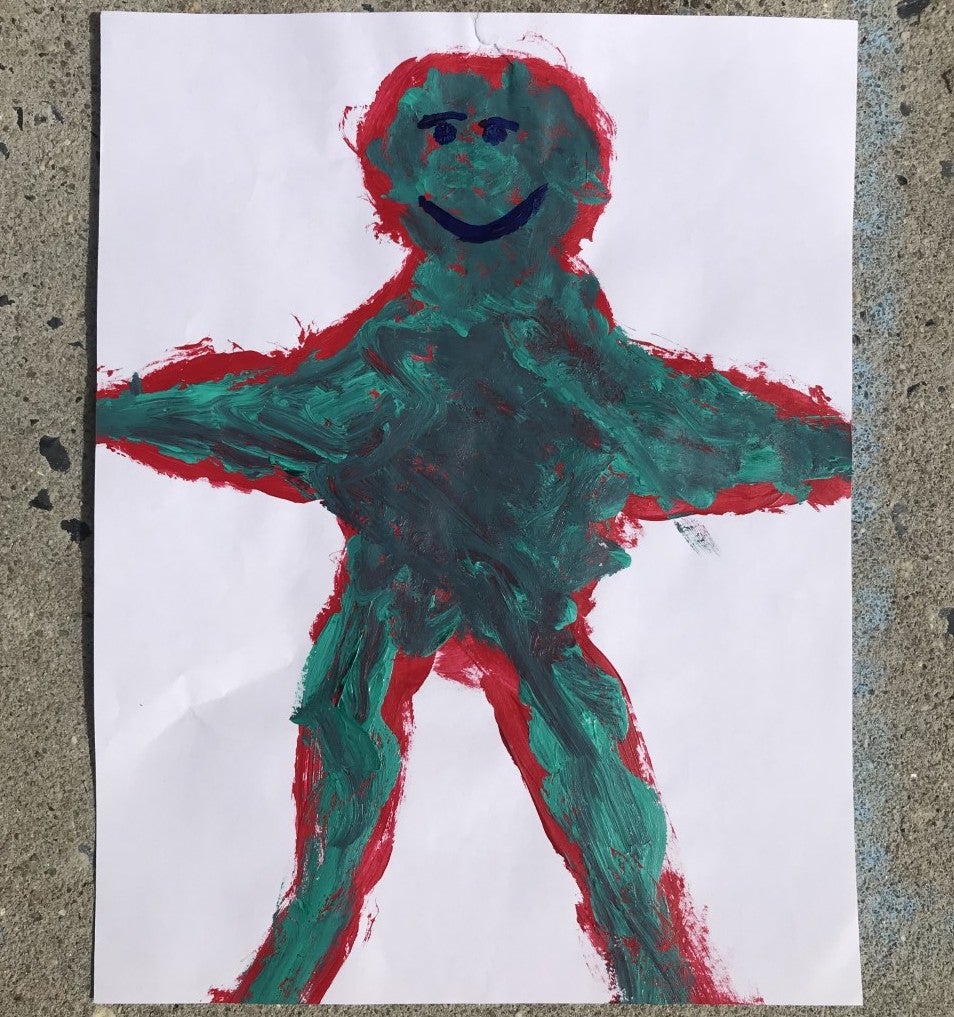

Shady Rose, the artist, incorporates their dreams into their creative work, which involves performance, writing, and visual art. Right now, they’re writing out a dream they once had that lasted for several weeks in the dream world. They want to publish it as a novella.

They’re also the lead singer in a band called Lightmare. Their lyrics often grow from the tenor of their dreams.

“We describe ourselves as ‘music from that one dream,’” Rose said.

How to remember your dreams

Some researchers, including Michael Schredl, have found personality differences between high and low dream recallers. On personality tests, dreamers score higher on traits such as openness to experience, extraversion, creativity, and anxiety.

But, beyond that, the best predictor of dream recall is simply showing an interest in one’s dreams. So if you feel motivated to remember your dreams more, here are some tips from Nirit Soffer-Dudek, a dream researcher and psychologist at Ben Gurion University in Israel.

- Retrace your steps. When you wake up, stay in the same position with your eyes closed, and mentally review your dreams for a few minutes. Then immediately write down or voice-record what you remember — even if it’s just a few key words, or fragments, or simply, “I didn’t remember any dreams today.”

- Morning is the best time for dreaming. The only way to remember one’s dreams is to wake up. That’s why people most often remember the last dream they had before awakening, even though we dream through the night. Hitting snooze can help you remember your dreams more, because you’ll drift in and out of slumber and your sleep will be more aroused. That mixed, or aroused, sleep can make dreams more intense or unusual — and you are more likely to remember emotionally intense and unusual dreams.

- Increase your REM sleep. Research now shows we dream in all phases of sleep, not just REM sleep, as previously thought. But our REM sleep dreams may be more vivid and narrative, and we are more likely to remember them. REM sleep mostly occurs later in the night, once we’ve gotten our slow-wave sleep out of the way. So it helps to get enough sleep in a night (not to mention the myriad other benefits sleep has on our physical and mental health). Alcohol and THC can also reduce REM sleep, so cutting out those substances can help trigger powerful dreams.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.