Using ‘big data’ to help keep small children safe

Listen

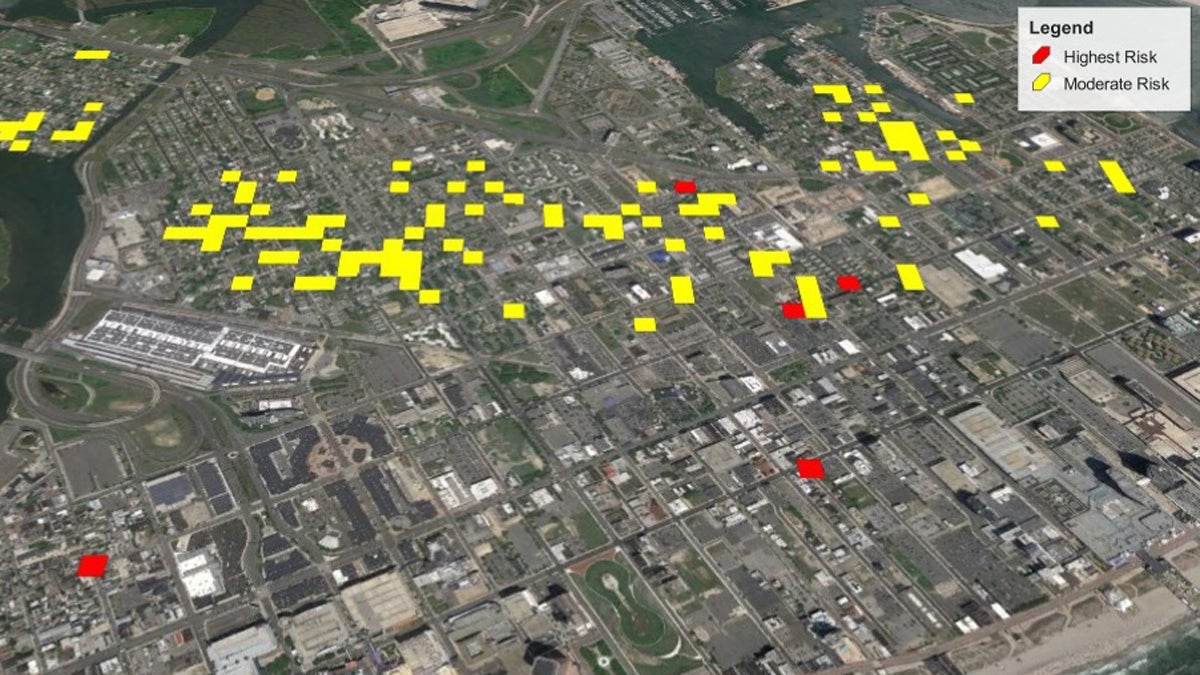

One example of predictive analytics through Risk Terrain Modeling. (Courtesy of Joel Caplan of Rutgers University)

Researchers in Fort Worth, Texas are mining data in search of abusers of children.

Doctors at Cook Children’s Medical Center in Fort Worth, Texas are used to treating cases of abuse, but what they’d really like to do is prevent it. So they’re experimenting with “big data” technology that could help predict neighborhoods where kids are most likely to be abused.

Sometimes, when a child who has been abused gets to the emergency room, it’s too late. Dyann Daley, a pediatric anesthesiologist at Cook Children’s, remembers a tiny toddler who had been kicked by his father in the stomach.

“We didn’t know exactly what the injury was when he came into the operating room,” she says. “But he had come into the hospital awake.”

Although doctors tried to keep him alive, the injury just wasn’t survivable. He bled to death during surgery.

“It was an emotional time because of the type of injury he had and how close he was in age to my own children,” Daley says.

In 2015, more than 170 children died as a result of abuse or neglect in Texas, according to the Department of Family and Protective Services. Tarrant County (where Fort Worth is located) has one of the highest rates of abuse in the state. Daley says no one really knows why.

“Some people say we’re better at catching it or better at reporting it,” she said. “I’ve worked in a number of children’s hospitals in Texas, and also in other places in the United States, and I’ve never seen as much physical abuse as I see here.”

Daley, who now runs Cook Children’s Center for Prevention of Child Maltreatment, has been on a mission to train doctors and nurses to recognize the signs of abuse early—like suspicious bruises or marks—but detecting abuse is hard. Especially for infants who may not interact with teachers or nurses familiar with the clues.

That’s where something called predictive analytics could be helpful.

“This technology has been used to predict where shootings would occur and other types of violent crimes, but no one had applied it to domestic violence, like child maltreatment before,” Daley says.

So here’s what her team did: First, they collected data on things like poverty, domestic violence, and aggravated assault. Then, they crunched the numbers using free predictive software invented at Rutgers University. It’s called “Risk Terrain Modeling.” It spit out a forecast for likely locations of child abuse in Fort Worth.

“Amazingly, we were able to capture 98 percent of the cases that occurred in the future,” Daley says.

In other words, the technology identified specific locations in advance, actual blocks in a neighborhood, where cases of abuse would likely occur.

Predictive analytics is a huge market; it’s part of a big data industry valued at $27 billion a year. And it’s only recently that these tools started being put to work by nonprofits and local governments.

U.C. Berkeley graduate student Darian Woods studied how predictive technology is being used to benefit children in potential danger from abuse across the world. So far, he says there have been some positive examples in places like New Zealand, Pennsylvania, and Los Angeles among others.

One success story he highlights is that of Hillsborough County, Florida. After a rash of child homicides there, the government boosted the number of social workers and used predictive analytics to pinpoint the most urgent cases of abuse. Since then, for those under court-ordered protection, the number of child homicides has been zero.

Woods warns that could be an anomaly, but he points to it as evidence that data may have an imporant role to play in community health.

Even if predictive technology does pan out, though, there are thorny ethical questions that come with using statistics to judge whether children are safe. Woods says researchers have to be careful about reinforcing racial inequities and targeting specific communities.

For example, if one of the risk factors the models take into account is whether the child is cared for by a single mother, and more single mothers live in communities of color, “then maybe the model might target communities of color more,” Woods says. “And so that may lead to more social workers being sent out and more children being taken from homes from those communities.”

Neglect and abuse, Woods points out, also happen in wealthy communities, places that might not be flagged in traditional risk modeling.

At Cook Children’s in Fort Worth, Dyann Daley wants to use predictive modeling to target resources, not people. She says knowing where the risk clusters are provides an opportunity to align prevention services in the areas that need it most.

Her team has big plans for this big data experiment. The next step: to use the same predictive software to forecast abuse hot spots in the state’s largest cities.

Lauren Silverman reports on health, science, and technology for NPR affiliate KERA in Dallas, Texas.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.