Undocumented teens unite through a painful, shared journey

Listen

El Sueno Al Futuro

A look at the mental health needs of undocumented immigrants.

In a lot of ways, Domingo is like other good kids his age. He has great manners. He does well in school – especially math class. And when he’s not doing his homework, he likes taking naps, going out with friends, and making music under the name DJ Bless.

But the story of how Domingo ended up as an 18-year-old sophomore at Benjamin Franklin High School is anything but average. On January 5, 2012, Domingo said goodbye to his family in Guatemala and set out on a journey to get to the U.S.

“That was a rough day,” he said in Spanish through an interpreter. “That day will forever be in my heart.”

At first, Domingo didn’t want to leave Guatemala. But his grandparents told him, that because he didn’t have parents, he needed to support himself and go to the U.S. for better opportunities. Domingo’s grandma paid a smuggler to take him across the border, with a group of others. The trip in total took about a month and a half. At one point, it got so cold outside that Domingo couldn’t feel his knees.

“Sometimes we only ate once a day,” said Domingo. “There were some that couldn’t keep walking. Some got cramps and they couldn’t continue and were just left there.”

Domingo made it all the way to Arizona, before running into immigration officers and entering federal custody as an unaccompanied minor – children who cross the border without parents or papers. Unaccompanied minors are typically from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Many are placed in foster care, group homes, or shelters around the U.S., as part of a program run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement under the Department of Health and Human Services. That’s how Domingo ended up in a West Philadelphia foster home, living with two other unaccompanied minors and their foster mom, who didn’t speak Spanish. While he was grateful to be in the U.S., he also missed his family – which made it difficult for him at times.

“When I first got here, I didn’t know anybody, and I didn’t trust anyone,” said Domingo. “And because of that, I couldn’t express what I truly felt.”

Domingo is just one of many thousands of unaccompanied children who cross the border alone and end up in federal custody each year. In the last two years, the number has nearly quadrupled to almost 25,000 in fiscal year 2013. In Philadelphia, there are around 75 of these youth in foster care administered by Lutheran Children and Family Service.

While the immigration debate continues to simmer in Congress, unaccompanied minors and other undocumented youth living in the U.S. face tough questions about their future and the unique situation of growing up as a teenager, without legal status.

Enter the youth mentorship group El Sueno Al Futuro – that’s Spanish for Dream for the Future. Domingo became a group member, after a caseworker at Lutheran Children and Family Service referred him to La Puerta Abierta or The Open Door – an all-volunteer project of the nonprofit Intercultural Coalition for Family Wellness. La Puerta Abierta runs the youth group and also provides free counseling to undocumented, mostly Spanish-speaking immigrants in Philadelphia.

La Puerta Abierta’s director and long-time family therapist Cathi Tillman says the group is a place for young people to meet others struggling with similar issues: things like leaving family behind, cultural adaptation, and even childhood trauma from their countries of origin.

“It’s everything from intense family turmoil, a lot of abandonment, unfortunately a lot of sexual trauma, physical trauma,” Tillman said. “Kids being married off when they’re very young, put to work for other families, taken out from school at a very young age.”

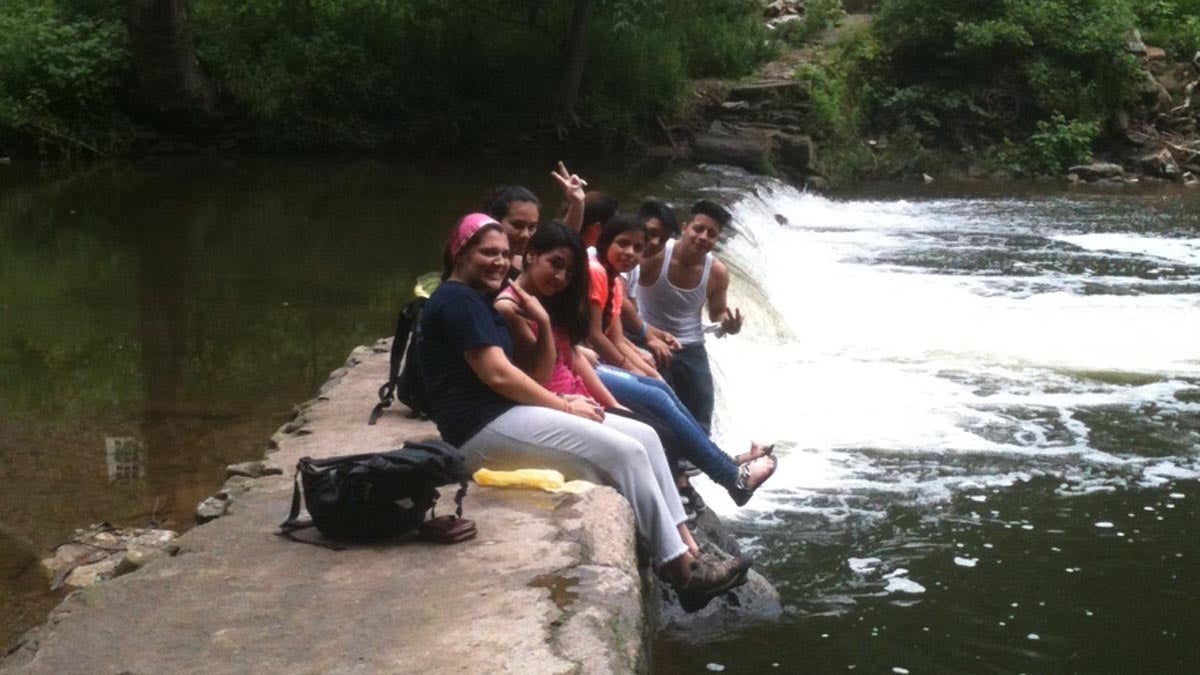

Every week, six to eight undocumented teenagers get together at the group’s South Philly headquarters to hang out and talk about their feelings. Sometimes they write. Sometimes they draw.

“Sometimes we share funny stories so we can smile, but then there are other times when we share difficult stories and then we cry,” Domingo said.

Group members are also just dealing with the regular problems of being a teenager, documented or undocumented.

Tillman said, “We all know that adolescence is that goofy time where there’s higher levels of impulsivity and trying to find your way in the world.”

But without U.S. citizenship, the stakes are much higher for making mistakes for undocumented teenagers, who could be deported.

“Whether it’s getting your girlfriend pregnant, or going out drinking and getting arrested and being in big trouble because you’re not here with legal status yet,” said Tillman.

While unaccompanied minors like Domingo tend to get immigration status eventually, others in the youth group have a much more uncertain future. Take Damara Telles, who crossed the border from Mexico with her family at age eight and was at a low point in her life when she first started attending the group.

“At that point, I was stressing about college because I’m an illegal immigrant from Mexico so I thought I couldn’t go to college,” said Telles. “Many people said we couldn’t go to college.”

Telles thought the only way was to get a scholarship or pay expensive out-of-country tuition herself. To save up money, she worked almost 40 hours a week, on top of going to high school and getting good grades.

Telles says it was very hard. She only had her Mondays off. “And I sat at home, read, and don’t speak to no one because that was my day to keep calm, stay home, and just relax.”

Telles can finally relax a bit more. She’s a freshman in college now and has been able to pay in-state tuition. But she still doesn’t have work authorization or a driver’s license – though that could change once she hears back about her application for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

Through all this, Telles says another important source of relief has been getting to blow off steam at La Puerta Abierta’s youth mentorship group. It’s even given her an opportunity to help other young people.

“It’s really hard for some of them because they’re here without anybody,” said Telles. “But we try to help them and stay with them and now we feel like a really big family.”

This report is part of a multi-media mental health journalism series made possible by the Scattergood Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.