The complex science of chocolate

Listen-

-

-

-

-

-

Lucy Kibe examines patient Sherri Robinson at St. Elizabeth Wellness Center

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

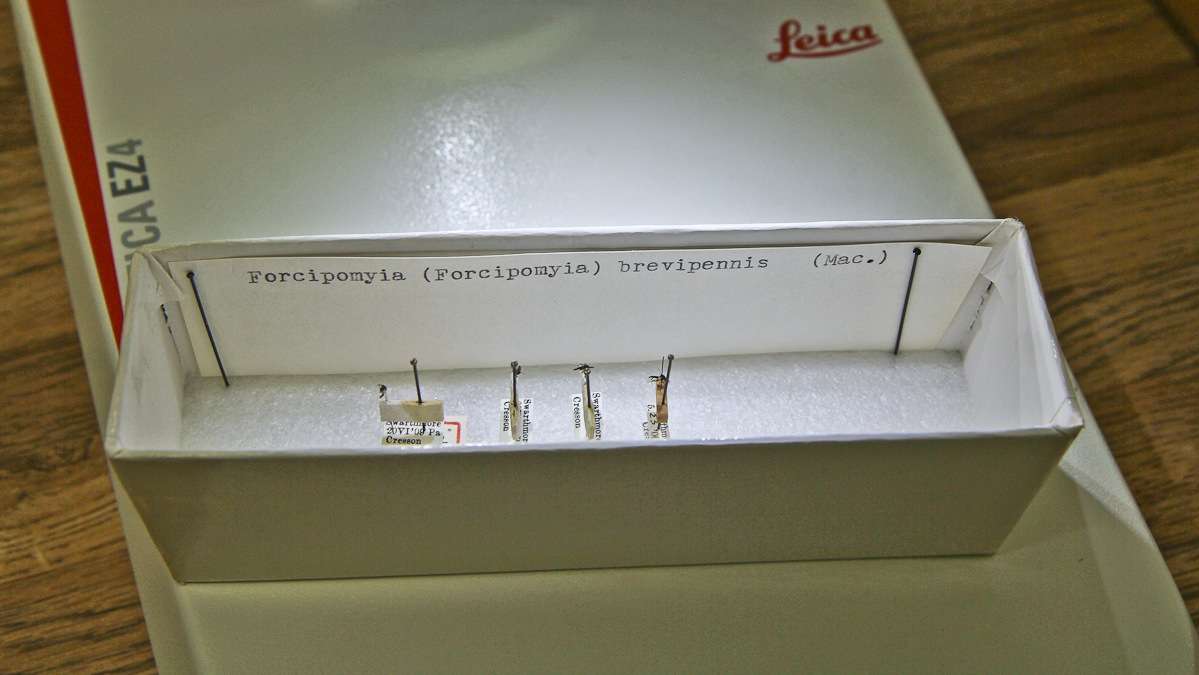

Biting midge flies may be one of several insects that help chocolate plants turn flowers into fruit.

This month, in Philadelphia, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University opens “Chocolate: The Exhibition.” It documents the huge economic and cultural reach of the chocolate industry, and also explores how chocolate is created. One aspect of that is an important interaction between the cocoa plant and insects, which scientists are still working to fully understand.

Biting midge flies may be one of several insects that help chocolate plants turn flowers into fruit.

Tatyana Livshultz, assistant curator in the Department of Botany at the Academy, says Logan Square in Philadelphia—just across from the museum–is a good place to learn about pollination, and get an up-close look at how that interaction between plants and insects works.

The flies and wasps that visits chocolate plants don’t live in Philadelphia, but there are lots of insects hard at work there transporting pollen (the male part of a flower) to the female part.

Pollination is how plant sex gets done—kind of. Livshultz says pollinators are more like matchmakers.

For flowering plants, on average, less than one percent of the pollen that leaves flowers actually arrives on another flower. The insect needs to be a frequent visitor—and bring the right kind of pollen.

To be most fruitful, Livshultz says flowers prefer foreign pollen from a plant that’s not closely related. The best pollinators don’t just buzz from flower to flower on the same tree, they travel far and wide.

An up-close look

The Academy stores dried and pressed samples of the cacao plant in its sixth floor herbarium. There are rows and rows of huge cabinets, and the air conditioner is turned up high.

“We keep it cold up here because–speaking of plant-insect interaction–there’s a species of beetle that specializes in eating dried plants,” Livshultz said.

There are specimens from Jamaica and Mexico, but those are likely cultivated plants.

Wild Theobroma cacao trees grow in South America, near the Amazon basin, and they like heat and shade.

“They’re short and in the wild they grow under a canopy of taller forest trees, and in cultivation, they might cut out some trees from a rainforest and plant Theobroma cacao in the understory,” Livshultz said.

Clusters of creamy yellow flowers grow directly out of the trunk of the tree. Often it is petals that entice insects, but on the cacao, the flashiest features are five ruby-red spikes at the center of the flower. We don’t know for sure, but botanists say those staminodes may also produce a bit of nectar to attract insects.

The pollinators

Chocolate is big business, but there have been surprisingly few studies on which insects actually help cocoa flowers become fruit.

“If you don’t have pollinators, you don’t get fruit, and if you don’t get fruit, you don’t have chocolate to sell,” Livshultz said. “One of the things I’m struck by is how little we know about pollination.”

Livshultz says part of the challenge may be that the insects that pollinate cacao flowers are so very small.

The academy has specimens of flies and wasps similar to those that visit cocoa plants. Forcipomyiinae flies–one group of biting midges—are as small as the head of pin.

Entomologist Jason Weintraub, manager of the academy’s insect collection, says the flies are best seen under a microscope.

One male is hairy, with a long abdomen, and eyes banded in black and bronze.

The midges at the academy collection aren’t the flies that visit chocolate plants, but they’re in the family.

“It’s a distant cousin of one of the tropical species in Africa that we suspect is a pollinator of cultivated Theobroma,” Weintraub said.

It’s fun to talk about the midge, but Weintraub says the list of potential chocolate pollinators is long.

Another pollinator candidate is a tiny wasp in the family Eulophidae. In South America, wasps in the same family also visit cacao plants.

“It’s not clear cut that one single family of flies, is necessarily the most important group of pollinators,” Weintraub said. “Everyone’s glommed onto that because there’s no other additional information.”

The science of chocolate

During a visit to the Hershey Company, head of product development, chemical engineer Jim St. John lead the tour and explained some of the science behind chocolate.

On tempering chocolate the artisan way:”So you think about carbon, you can have a graphite pencil or you can have diamonds. What you want is the cocoa butter crystal to be in its tightest packing form, that’ll keep the melt temperature higher, so you can pick it up with your hands, and it doesn’t melt all over the place all the time,” he said.

On why chocolate is a good vehicle for other flavors:”So you put in your mouth, and it’s at that perfect temperature, it spreads across your palate, and it more or less carries flavors with it, and there are certain flavors that go very nicely that way–caramel, vanilla and probably, I think, the best one is peanut butter.”

On putting peanut butter in the refrigerator:”Those flavors have to evaporate and get up in to your nose cavity. So if it is refrigerated, and you’ve got to warm it, you’re just delaying that sensation. If it’s room temperature, it hits your nose much faster, and you get that full intense peanut flavor.”

On the science of making a good Reese’s cup:”You have to worry about things like oil migration. Peanut oil is liquid at room temperature. Cocoa butter is hard at room temperature. So, those two things, they’re not really very compatible.”

On bitter chocolate:”There’s a general trend as you grow older, you tend to like bitter more. Some people think that sweetness is the last receptor that kind of goes. So as a kid you are getting all these flavor and sweet, but as you mature, other receptors die off, and you are left with sweet. One flavor chemist told me that if you say that’s too sweet for me, you’re really saying I’m getting old.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.