Songbird nesting habits may indicate severity of hurricane season

A Delaware professor is using a migratory bird species that nests in Delaware to predict the severity of the coming hurricane season.

Listen 5:33

This veery songbird can predict the severity of the coming hurricane season more consistently than meteorologists, according to research published this month by Delaware State University professor Christopher Heckscher. (Courtesy DSU)

Hurricane season is officially underway, but its peak won’t arrive until mid to late August. The National Weather Service predicts this year’s range of storms will be about average, possibly above average, with 10 to 16 named storms and one to four major hurricanes.

Those predictions use sophisticated computer modeling, but other prognosticators look to the trees in compiling their forecasts.

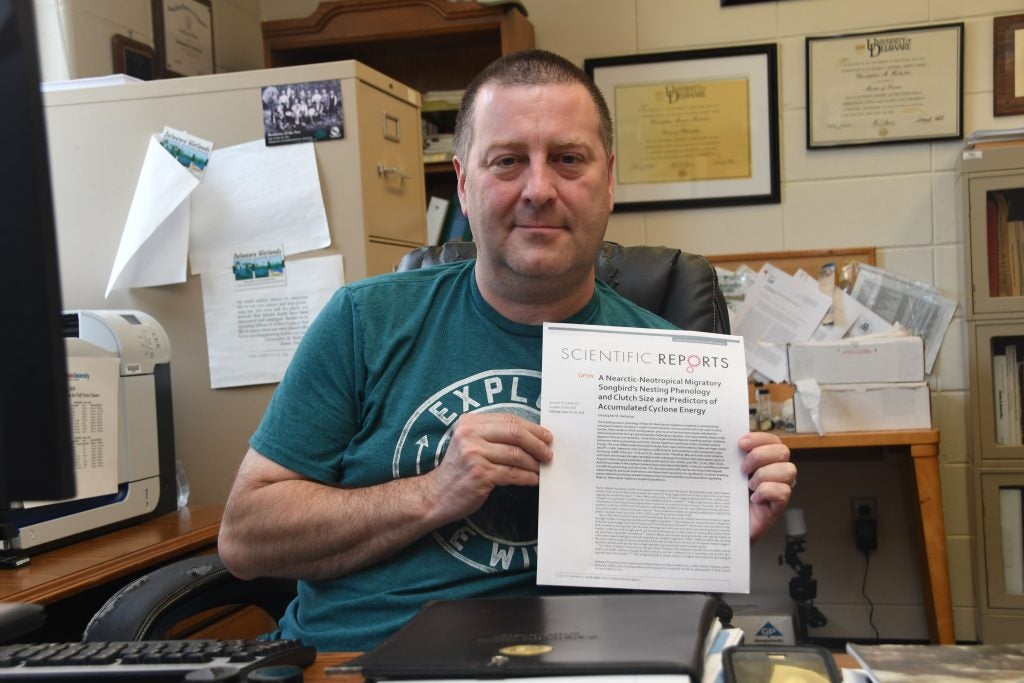

Delaware State University professor Christopher Heckscher has just published a study in the journal “Nature” that says the breeding habits of a migratory bird species nesting in Delaware can predict the severity of the coming hurricane season.

Like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, animal behavior can provide important clues about nature that humans can’t necessarily perceive or predict. But it’s not a canary that Heckscher is using for his hurricane outlook; it’s a thrush species called veery. The small birds, similar to robins, rarely leave the forest and so may be less familiar to most people. Veeries spend their winters in Brazil before migrating north to nest in Delaware and other parts of the Mid-Atlantic region.

Since 1998, Heckscher has been watching veeries at White Clay Creek State Park in Newark, Delaware. They typically arrive in mid-spring and start laying their eggs in early May. After noticing that the birds ended their breeding period earlier in some years, he started seeking the reason. After looking at the data, he eventually landed on a correlation between the nesting habits and hurricane season.

After studying the bird’s habits over that time, Heckscher discovered that when the veery breeding season was longer, hurricane season tended to be less severe. Short breeding times were followed by more severe storms. Less severe storm seasons also occurred in years the veery had more chicks.

“Maybe tropical storms might be something that they’re trying to avoid or perhaps get to South America a little early, so they might skip some of the peak of hurricane season,” Heckscher said.

“If you’re a little bird, and you have to migrate down to Brazil, which is where they spend the winter, you want to make sure that you’re going to have a safe flight,” he said. Small birds that typically fly over the Caribbean Sea during the height of hurricane season could die in a severe storm.

“If they stop nesting early, they might have more time to migrate during the fall, they might have a longer period of time to get ready to migrate before they leave Delaware,” Heckscher said.

But the birds’ timing isn’t always right. “It’s not 100 percent, so some years they are off,” Heckscher said.

Still, the birds beat the record of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other experts, he said.

“It’s actually turned out that the veery are better early season predictors of the following hurricane season than some of the other major meteorological groups,” Heckscher said.

So how do these little birds make such accurate predictions? Heckscher hypothesized that the veery can detect something in the atmosphere or environment that meteorologists aren’t looking at right now. The key to their instinctive action may be linked to some environmental signal in South America where they spend eight months of the year, he said.

“They’re using something out there that’s a pretty good predictor that — so far, at least it appears — is a better predictor than some of the parameters that meteorologists have been using,” Heckscher said.

He said he hopes researchers will be able to figure out what the birds sense in the environment, so forecasters can also use that information in making their predictions.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.