Remembering Patient H.M.

Listen

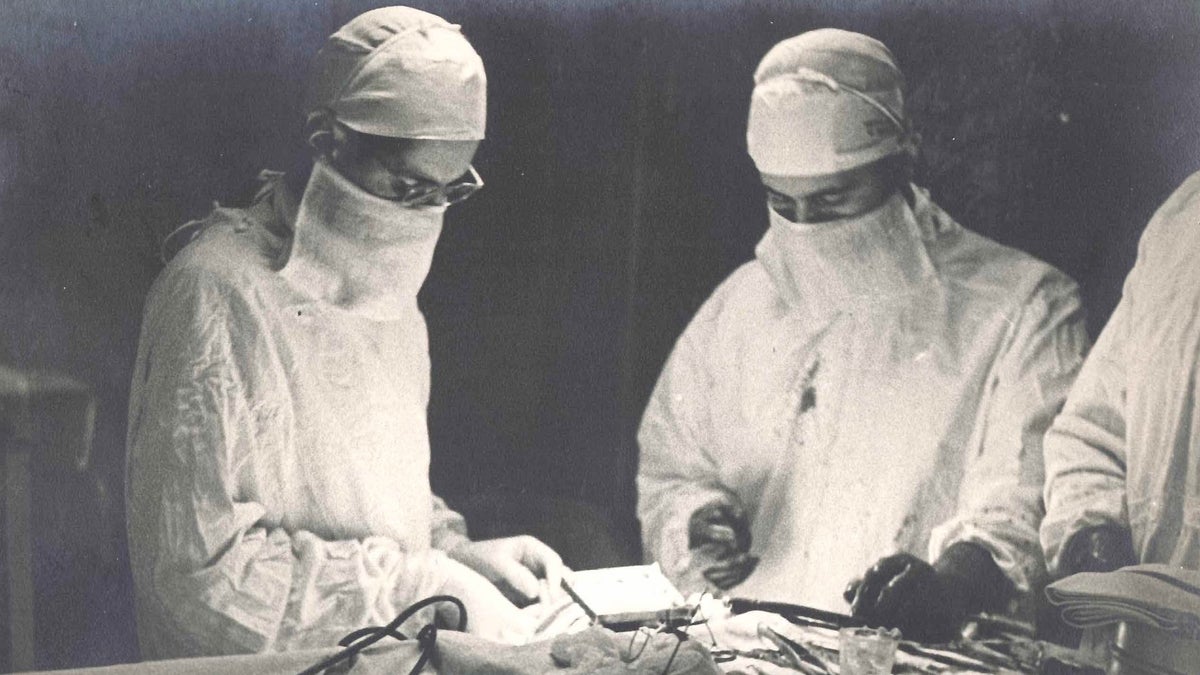

Dr. William Beecher Scoville (on left). (Courtesy of Luke Dittrich)

A new book uncovers some hard truths about early attempts to cure brain disorders with a scalpel.

When Dr. William Scoville removed part of the brain of Henry Molaison in 1953, he had hoped to cure Molaison’s severe epilepsy, but the result of surgery was a forever damaged mind that became what some call the perfect test case for the relationship between our memory and the structures of our brain.

“The present moment would just sort of slide off of him,” says Luke Dittrich, author of “Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets,” “[Molaison] lived the rest of his life—more than a half century—in 30-second increments.”

Dittrich documents the story of Molaison, who became known as “Patient H.M.” to the scientific community, and who contributed profoundly to our understanding of our minds. But, to put a twist on the narrative, Dittrich tells host Maiken Scott that Scoville, a respected surgeon of his time, was, in fact, his grandfather.

“This has been part of my family lore for as long as I can remember,” said Dittrich. “I think I always knew that this was a story that at one point I was going to have to tackle.”

Dittrich says that, though he never discussed Patient H.M. with his grandfather (Scoville died when his grandson was just nine), the family generally viewed Molaison’s condition as a regrettable but isolated mistake. But Dittrich found out that his grandfather honed his surgery skills on vulnerable and powerless patients in psychiatric hospitals. He discovered what he called a “chilling letter” that described the “unlimited access” to “human material” that his grandfather had been given in one asylum.

“In order to understand the story of Patient H.M., you really had to look at this long-term campaign of what’s hard not to call human experimentation that was conducted in asylums and hospitals around the country.”

Dittrich said that Molaison’s story isn’t just one of science, but of how we pursue knowledge about ourselves: “His case does raise some questions of research and medical ethics that should never be forgotten.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.