Redina’s story: A mother’s troubled journey home from prison

Redina Rodriguez was released from Pa. state prison one year ago and says she wants to change. But the odds of her staying out are long, while the stakes couldn't be higher.

This story also can be experienced as a radio documentary. To listen, click the play button above or download the podcast of this special Nov. 27, 2017 episode of WHYY’s NewsWorks Tonight on Apple Podcasts or Stitcher. The story was reported and produced by Katie Colaneri, edited by Sandra Clark and Eugene Sonn. Charlie Kaier engineered and mixed the sound for the documentary.

—

It’s late December 2016, and Redina Rodriguez is standing up in front of the classroom in a Philadelphia high-rise, reading off a sheet of notebook paper the things she wants to put behind her:

“I’m leaving behind drinking, DUIs, prostitution, jail, drugs, resentment, using people, co-dependency, selling drugs, impulsive thinking, the streets, negative behaviors, rebelling, stealing, manipulating, and lying.”

Redina, then 48, is one of a dozen formerly incarcerated women taking part in a 10-week program called Women Working for a Change, run by the Philadelphia anti-violence group Mothers in Charge. Now, it’s Week 5, the halfway point.

Redina wants to change. And, she says, she really means it this time.

—

Outside during a smoke break, Redina tells me she’s been in prison for 11 of the last 17 years. She was released on parole a month ago.

Redina committed her first crime 25 years ago. It was 1992. She was 24.

“I had a difficult childhood, and, instead of turning to drugs, I turned to relationships,” she says, “and I turned to the first drug that the guy I was in a relationship had — and it stuck.”

She got hooked on crack cocaine.

Redina and a friend were arrested for forging about $450 in checks and cashing them at Pathmark and Giant grocery stores in Central Pennsylvania, where she grew up.

Eventually, Redina pleaded guilty to three felony charges and was sentenced to 23 months probation. That touched off a vicious cycle of addiction and probation violations that went on for years.

Then, in late 1999, Redina left the county without permission. She was eventually found at a notorious crack house in Harrisburg and brought before a judge in Dauphin County for yet another violation.

Reading the court transcripts, I can see the judge really threw the book at Redina. He scolded her for thinking she could do whatever she wanted and get off easily by giving him a “sob story” about her children.

“Guess what?” the judge said. “The string has run out.”

He resentenced her to three to 21 years at SCI Muncy, a state women’s prison in Northeast Pennsylvania, but that didn’t stop the cycle. Redina went in and out of prison five times for violating parole by using drugs. The sixth time she was sent to prison was for a DUI in 2014, her first new charge in more than two decades.

“I always thought like, ‘Oh, I’ve been screwed by the justice system because I got three to 21 years. I’m doing time that murderers get, for being an addict,’” she says. “At the end of the day, what I’m learning is, it’s a choice … you can use or not use.”

High rates of recidivism

The last 25 years of Redina’s life mirror a perennially troubling statistic: Every month, about 1,800 people are released from Pennsylvania state prisons and more than half of them — 60.9 percent — will be arrested again or back behind bars within three years. Nationally, the recidivism rate is 67.8 percent.

“And this has not changed for 20 or 30 years. We’re seeing the same recidivism rates, even though we’ve had all this focus on re-entry since early 2000,” says Christy Visher, director for the Center for Drug and Health Studies at the University of Delaware.

Visher has been studying prisoners’ re-entry to society for more than 15 years. She says within the first six months of release, former inmates have a higher risk of dying — from an overdose, health problems or going home to violent communities — than the general population.

“This six months is really critical and, unfortunately, re-entry specialists haven’t really understood the importance of this particular period,” Visher says.

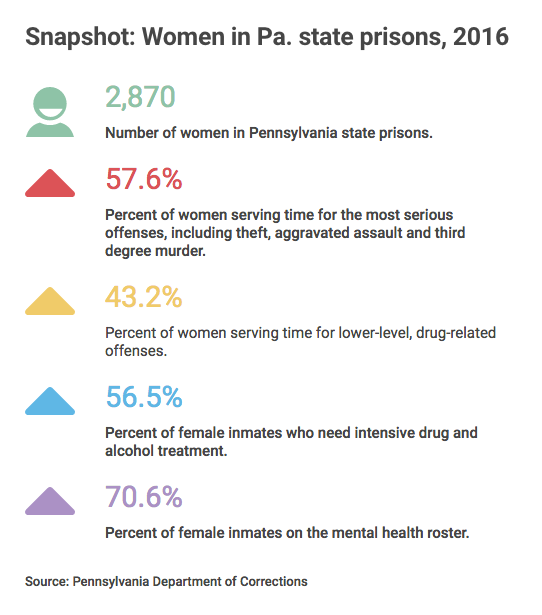

For women in the system, the road after release can be even more difficult — and the number of women behind bars is on the rise.

Across the United States, eight times more women are in prison today than there were in 1980, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. In Pennsylvania, it’s 10 times more. But, because the criminal justice system is overwhelmingly male, far less is known about women offenders and how best to help them when they are released.

Visher says research has found women are more likely than men to have serious mental health problems and to struggle with addiction.

In Pennsylvania last year, almost 60 percent of female inmates in state prisons required intense substance-abuse treatment, compared with about 40 percent of male inmates. And 70 percent of female inmates were on the mental health roster, compared with about 25 percent of male inmates.

Another shot at motherhood

For Redina, her kids are a major part of coming to terms with her past.

“They all suffer from abandonment, every one of them, and I know that I play a part in that,” she says.

Redina has five children — all adults now, except for her youngest, 13-year-old Jordyn. They were all raised by myriad relatives and foster parents, and, for much of their childhoods, Redina wasn’t there.

The effects of her absence were especially damaging for her older daughters. One is in the throes of heroin addiction. Another, 23-year-old Kylie Hess, told me she attempted suicide when she was 16 by slitting her wrists.

“I don’t want to blame her [Redina] because I know that addiction is a disease, but I’m mad,” said Kylie, who currently does not speak to her mother. “I’m hurt that this is something that she chose over five children.”

Redina kept in touch, often sending beautiful, handmade cards from prison, but those notes never filled the void.

“She gave birth to five kids that are all raising themselves,” Kylie said. “And, I hate to say it, but I’m surprised none of us are dead.”

Redina says gnawing guilt over her failures as a mother used to drive her back to using drugs and alcohol. A penchant for manipulating men also fueled that cycle, as did the emotional wounds of her own chaotic childhood — Redina says she grew up feeling unloved and unwanted, and that she had been sexually abused by her stepfather.

Now, Mothers in Charge is trying to help Redina work through those feelings and take responsibility for her past choices, so she can move forward with her life.

She recently reunited with her youngest after not seeing Jordyn since she was 6.

“On my way there, I told her I missed the bus and I wouldn’t be there til 9 o’clock at night and she was really upset, but truth is, I got there on time,” Redina says. “And I walked up to the door with a caseworker, and she almost knocked the caseworker over coming out the door to get to me.

“And when she hugged me and just started sobbing in my arms, it’s like everything in the world was OK … because she loved me, because she forgave me. And at that moment, I knew that it was going to do anything to do right by her, too.”

Reconnecting formerly incarcerated women with their children is the larger goal of Women Working for a Change or WW4C, says Dorothy Johnson-Speight, the founder of Mothers in Charge.

She says WW4C is the outgrowth of another program Mothers in Charge runs at Riverside Correctional Facility, Philadelphia’s all-female prison.

“The women that we were working with at Riverside oftentimes lacked resources and supports when they came home, and this was a reason oftentimes for their violation and that they would end up back in prison,” she says. “So we started to think, how can we keep these women home with their families?”

The organization turned to “Thinking for a Change,” a curriculum developed by the National Institute of Corrections and rooted in cognitive behavioral therapy, which boils down to this: If you can change the way someone thinks, you can change the way they act.

“So that was our goal, that we would help these women to change their thinking, so that they could change their behavior,” Johnson-Speight says. “So that they could be home with their children and their children would not become victims or perpetrators of violence or worse — you know, be murdered or end up in a penitentiary, as well.”

Redina and the dozen other women in her WW4C cohort are paid $200 a week to work — although, not in the traditional sense.

Aside from writing resumes and looking for job leads, the women are working on how to deal with some pretty complex emotions and coming to terms with the trauma they’ve experienced.

At Mothers in Charge, there’s also a strong emphasis on spirituality, leaning on God when the going gets tough, and on helping the women accept their checkered and painful pasts, while learning to let them go.

It can be intense.

Like this moment with one of the class facilitators, Sharon Thomas, who herself is a recovering addict:

“It’s the ones that love you the most that hold you more accountable for the stuff you’ve done! ‘Cause we hurt our families, we forgot that! Sometimes it takes 15 years, and they still want to hold that over your head, but that’s up to you how you receive that. I don’t receive it. I don’t.”

A ‘miracle drug’ and a change of scenery

After so many years of cycling in and out of prison, what’s different for Redina this time?

She says the switch flipped in 2014, the last time she was arrested.

“It used to make me mad when I got caught because I wanted to keep going, I wanted to keep running,” she says. “But this time, I can remember when I got arrested for my DUI, a feeling of relief washed over me. I can remember praying and telling God that I’m tired … I’m tired of living like this. This isn’t me …

“And I didn’t really believe in myself at that point like that I could stop or that I could change. I just knew that I had the willingness.”

But Redina is also getting some help that wasn’t there the last time she got out.

One month before she was released, Redina opted into a state program that gives returning inmates a medication called Vivitrol. The monthly injection blocks the opiate receptors on your brain — so if you were to drink a lot of alcohol, for example, you still wouldn’t feel drunk.

“I consider it to be like a miracle drug because by now, I would have had a craving to use,” says Redina, who has struggled with addictions to alcohol and prescription pain pills, as well as crack cocaine.

The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections gave her the first shot before she was released and is helping her get 11 more, along with counseling and group therapy.

Another big change is that this time, Redina didn’t go back home to Harrisburg after she was released. Instead, she was sent to a halfway house in Philadelphia, and her counselor there got her an interview with Women Working for a Change.

Redina has big goals now.

A gifted artist who spent some of her time in prison teaching fellow inmates to paint and draw, Redina wants to become a certified art therapist.

She also wants to get back custody of her daughter Jordyn. To do that, she needs to find a stable job and a place to live.

But as the big Mothers in Charge graduation ceremony in mid-February draws closer, it becomes clear that the warmth and support of the women in her program can’t shield Redina or her classmates from the realities facing the millions of Americans with felony convictions.

The night before the ceremony, Redina calls with some bad news. She’d submitted a request to state parole to leave the halfway house and move into a friend’s apartment back in Harrisburg. Her request was denied.

Redina says her friend had spoken to the landlord who’d said no problem.

“And then the head lady called back and said, ‘Well, I don’t know who you talked to. They shouldn’t have told you that … because we do not allow people with felonies in our complex,’” Redina tells me.

And, unlike some of her fellow graduates, she doesn’t have a job or another program lined up yet.

“Every day, I was making marks, and I was bettering myself there,” she says. “And it’s hard when you go from four days a week, eight hours a day, you know putting so much of yourself into a program and then, boom — you’re done. Now what? Now what am I going to do?”

The anxieties of the night before seem to have dissipated by the following evening, when Redina is wearing her shiny blue cap and gown. The excitement is palpable as she and her 12 classmates flit about the room fixing their hair and makeup, taking selfies with each other.

The nerves kick back in when it’s time to line up in the hallway outside a large meeting room at the School District of Philadelphia’s headquarters in Center City where the ceremony is about to begin.

The women march slowly up to the front of the room, passing tables of past graduates, their friends, family members, and some of their children.

No one is here for Redina.

But she seems gratified by the applause, when she gets up in front of the mayor of Philadelphia and other dignitaries to tell her story.

“OK. Hi, everybody! My name is Redina Rodriguez. I’m a 48-year-old mother of five beautiful children and two amazing grandchildren,” she says. “Because of what I’ve learned at Mothers in Charge and Women Working for a Change, my affirmation is, ‘When we accept our imperfections, no one can use them against us.’”

‘I have to have faith in her’

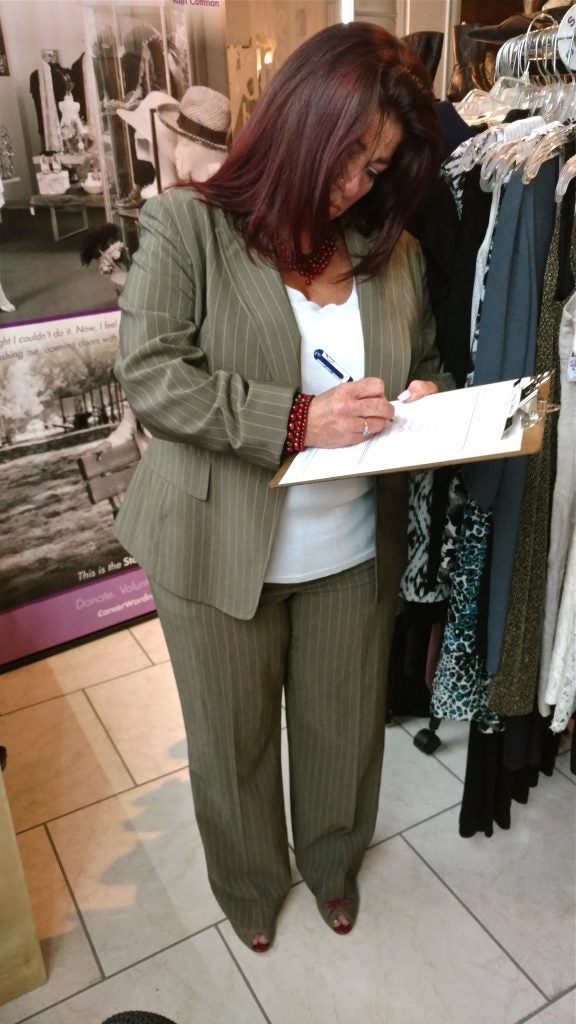

The next time I see Redina two months later, she’s dressed to the nines, wearing a taupe pantsuit with thin white pinstripes and matching peep-toe pumps decked with tiny red bows.

It’s a rainy afternoon in April, and Redina is modeling for me outside the dressing room at Career Wardrobe, a Philadelphia nonprofit that helps women struggling to find work get the right look for job interviews.

“I was discouraged for a little while because … I was applying every day for jobs, and it just didn’t seem like anything was happening,” Redina says. “And then, all of a sudden, all these interviews kept popping up every day.”

She says her favorite was at the Philadelphia Zoo, where she had applied for a job giving pony rides to children.

“But it only paid $7.50 an hour, so unfortunately, I can’t raise my daughter on that,” she says.

For now, her career in art therapy is on hold, replaced by the need to find a job — any job — that will pay enough to support herself and Jordyn.

Redina’s also struggling to decide where to live. She really wants to go back to Harrisburg. It’s more affordable, and she knows how to get around without a car. Plus, she has a lead on a recovery house out there and was offered a job at a nearby fulfillment center, making $12.75 an hour.

But Harrisburg is where the darker parts of Redina’s past — the people, places, and things associated with her addiction — could come back to haunt her.

And now she has a second interview in Philadelphia at an insurance company, and she’s going to give it a shot.

All Redina knows right now is that she wants to leave the halfway house where she’s been living for five months — Gaudenzia DRC, a tan-colored building complex in the East Falls section of Philadelphia.

Whenever Redina and the other residents want to leave, they must get passes signed by both their parole officers and Gaudenzia staff in advance. And when they enter the building, they have to pass through metal detectors and be patted down by security guards.

“They’re going up between your legs, and they’re going across the bra and down the middle, and it’s ridiculous and it’s violating and it’s demeaning,” she says. “This is supposed to be a step towards society.”

As much as she hates the controls, Redina admits that, in many ways, the limits that come with living in a halfway house have been good for her. But the longer she’s there, the more she longs for her own place where her youngest daughter, Jordyn, can live with her.

“I see a vision where I never saw a vision before,” she says. “I see myself with a stable home … I see myself stable in that home working a full-time job. I see myself paying bills, and being reliable and responsible. I see my children being able to come over whenever they want to come over, knowing that their mother’s house is going to be there.”

But making that vision a reality could still take months, maybe even years.

For now, she’s settling for a hotel room in Northeast Pennsylvania.

Every other weekend, Redina takes a nearly six-hour bus ride up to Williamsport, where she and Jordyn spend time rebuilding their relationship. The hotel is paid for by the local county children and youth services agency.

Jordyn lives in Williamsport with her adult half-sister, but she was raised by her grandparents in New Jersey.

On this Sunday morning, Jordyn’s working on her application letter to Milton Hershey — a private boarding school in Central Pennsylvania for disadvantaged kids. Redina is giving her advice, suggesting Jordyn needs to find a way to stand out, perhaps by writing about why she wants to be a correctional officer when she grows up.

Jordyn explains that, back in New Jersey, she worked at her uncle’s karate school, coaching younger kids. But Jordyn wasn’t just showing them how to kick or punch. She also coached them on conflict avoidance, how to be centered in their bodies and minds.

“I like to instruct a better mentality into them,” Jordyn says. “So I ended up tying that into correctional officer … like if I could help inmates go into a better path, like my mom’s going to a better path after she got out, I feel like I could be a really good source for them. Not a lot of inmates have visitors, family, or people that are there for them. They’re all on their own.”

Redina and Jordyn haven’t spent this much time together since Jordyn was 2. Their resemblance is obvious, especially in their long, dark curls and silly sense of humor. At one point during the visit, they start play-wrestling, rolling around on one of the beds and giggling.

Before they check out of the hotel, I ask Jordyn if she worries things with her mom will go back to the way they used to be.

“There’s always a thought like … an addict like might relapse, but I have faith in her,” she says. “I can’t really doubt her. I have to have faith in her or else this won’t work.”

Jordyn isn’t the only one feeling optimistic about Redina’s progress.

“It’s like night and day. She’s come so far … She’s what you hope for in the system that change can happen,” says Crystal Minnier, Jordyn’s caseworker.

Crystal has been with Lycoming County Children and Youth Services for 30 years. Many of the kids she worked with at the start of her career are parents themselves, parents with kids Crystal is now responsible for protecting.

She says many of those parents would be back behind bars or would have relapsed by now. But, so far, Redina is staying on track.

“If her recovery was in jeopardy, we wouldn’t see this,” says Crystal, who thinks if things keep going this well, Redina could get custody of Jordyn within a year.

Just six days after I spent the day with Redina and Jordyn, Redina sends me a text saying she had moved to that recovery house near Harrisburg.

A month later, on Memorial Day, I go out to visit her. The house is in Lemoyne, a small suburban town just across the Susquehanna River from the state Capitol.

Redina greets me on the front porch and shows me around the living room and kitchen. Then, she takes me upstairs to her bedroom, decorated with hot pink leopard print curtains and a matching bedspread. A dark-red betta fish swims in a bowl in the corner. There’s a shelf loaded with perfumes and a closet stuffed with thrift store clothes and purses – evidence Redina is relishing her first time living without a roommate in more than two years.

Redina seems happy here, but exhausted. She’s been working the late shift at a fulfillment center for an online pet supply company, driving around a cart and lifting heavy bags of dog food from 5 p.m. to 3:30 a.m. And she’s going to at least four Narcotics Anonymous meetings a week — recovery house rules.

Redina says being back in her old haunts has been easier than she thought.

“I’m very centered in my thinking and … I guess I just don’t want a bad ending in my story,” she says. “That and I just … I don’t want to go back. I don’t want to go back.”

That last thing Redina said — about not wanting a bad ending to her story — would haunt me for the rest of the summer. I would often lie awake at night wondering why she’d said that. Did she have a reason to think her story wouldn’t end well?

About a month later, Redina stopped picking up my calls.

A turn for the worse

In early August, I finally reach her daughter’s caseworker, Crystal Minnier. She tells me she also hasn’t heard from Redina in weeks, but the last time she saw her, things weren’t good.

Redina had traveled up to Williamsport the first Friday in July for one of her weekend visits with Jordyn. Crystal says she dropped them off at the hotel, then the two of them met up with one of Redina’s friends for pizza.

“Next morning, I get this frantic call from her daughter saying, ‘She left me at the hotel two hours after you dropped us off and never came home, and I called all night,’” Crystal says.

Jordyn woke up the next morning to the sound of the hotel phone ringing. It was the concierge telling her an Uber was downstairs to pick her up. The driver took her to Redina’s friend’s house.

“A half-hour later, she ended up turning up there, and she was crying, and she tried to hug me,” Jordyn tells me on the phone in October. “And she was like, ‘I missed you,’ and I was like, ‘Please don’t touch me … why are you lying to me?’ ”

Redina told Jordyn she had left her phone at her friend’s house and had gone back to get it. Then, she went to buy them some food … and then, her phone died.

Eventually, Redina admitted what really happened.

“She was like, ‘Well, I ran into your dad.’ I was like, ‘You don’t just run into him. I don’t even just run into him, especially at like midnight or something,’ ” Jordyn says. “She’s like, ‘I ran into your dad, and he offered me some drugs.’ I’m like, ‘You should have said no and turned away.’ But she ended up doing drugs with him and then, she was walking down and a man picked her up. He so happened to have drugs, too.”

About six weeks before that night in July, Redina had stopped taking Vivitrol, the monthly injections she was getting to help treat her addictions to drugs and alcohol.

When Redina moved back to Central Pennsylvania from Philadelphia in April, she needed to change her health insurance, but learned her new plan wouldn’t kick in until July. Redina was referred to a mobile clinic, but the nurse who runs the clinic says she didn’t know Redina was part of a state program giving Vivitrol to returning inmates. That means if Redina’s insurance wouldn’t cover it, the state would have paid for the shots, which go for about $1,000 each.

Not knowing, the nurse instead prescribed Redina the same medication in a daily pill form. At some point, Redina stopped taking the pills.

Three days before her new insurance was supposed to kick in, she relapsed.

It started with a shot of vodka. Soon, she was back on crack.

While Vivitrol is not an effective treatment for people taking stimulants like cocaine, it has worked for Redina, who was prescribed the drug for her history of abusing alcohol and prescription pain pills.

Crystal thinks it’s clear what prompted Redina’s relapse: red tape.

“I can’t tell you how many times those kind of things happen. There are glitches that are ridiculous,” she says. “If my insurance lapses for some reason, and I can’t get my thyroid pill, I’m not going to risk death. That’s a little different than someone like Redina that absolutely needs to have it. You found something that works. She can’t be without it.”

In September, Redina and Jordyn had a hearing in family court.

The court hearing officer ruled — at Jordyn’s request — that it would not be in her best interest to continue her visits with her mom. The court hasn’t terminated Redina’s parental rights, but for now, she’s no longer allowed to contact Jordyn.

Not long after that, Redina relapsed again.

“I’m not really sad,” Jordyn says. “I’m more like angry for her.”

Jordyn turned 14 in August. She thinks she might try to reconnect with her mom when she gets older, but for now, Jordyn says things have gotten better since she cut off contact — her grades are up, and she has more time for her friends.

“I didn’t want to end up in the same place my sisters did,” Jordyn says. “They were worried about her throughout their whole life, like … Is she going to relapse? Is she OK? Are we going to have a relationship now? I didn’t want it to be like that. I didn’t want my life to revolve around what she did and how it affected me.

“I guess I wanted to move on a bit,” says Jordyn, who is on the waiting list at the Milton Hershey School and hopes to finish high school there.

The right thing?

On a Friday morning at the end of September, I finally reach Redina. Her voice is hoarse, and she sounds drained. She tells me she’s checking into rehab as we speak.

On Halloween, I drive to a treatment center in Shippensburg to pick her up for our last interview.

A nurse helps load Redina’s backpack and suitcase into the trunk of my car and says goodbye to her in a way that’s so cautiously encouraging.

“All right, Redina, good luck, OK? I’m very glad, you look 100 percent better,” the nurse says. “Hang in there, OK? Good luck — you’re going to be great.”

Redina seems ready to take on the world again with a vengeance. The moment the car door shuts, she launches into her version of the events that led to her relapse and shares her new plan to approach the future “one day at a time.”

“Oh, we have so much to talk about,” she says.

Five months have passed since I’ve talked to Redina in person, and as we make the hourlong drive back towards Harrisburg, she turns angry and resentful, a side she’s not shown before.

A longtime friend who’d been supporting her financially — paying her rent and her phone bill — is cutting her off. And then there’s Jordyn, who’s joined two of Redina’s other children in ending communication with her.

I ask Redina if she thinks that’s the right thing for her family to do, and she pauses for a long time.

“So do I think it’s the right thing? No, I would prefer that they, even though this is not the first time I’ve relapsed, I would like to think that they could try to support me because their support for me would, oh my God, it would shoot so much motivation into me if I, if I have them …”

Redina lets out a deep sigh.

“This is such a hard topic for me because the part of me that desperately wants them in my life says, you know you need to support me, you need to be there, you need to forgive me,” she says. “But then, the part of me being a mother who does love them and does want to protect them, also knows that they need protection from me and my addiction.”

‘A heart change’

It’s no secret people coming home from prison face many challenges as they try to re-enter — struggling to stay sober, finding someone willing to hire them or rent them an apartment, despite their criminal records. That’s why 60.9 percent of former Pennsylvania inmates like Redina will be arrested again or back in prison within three years of their release.

Although unlike many others, some of those things came easier for Redina in her first year out from behind bars.

If you ask her what it takes to beat those odds, she says it’s not a 10-week program, a job or even a “miracle drug.”

“It’s a heart change,” Redina said back in May, sitting on her bed at the recovery house. “It has to be genuine and it has come from inside you, and if you haven’t made that decision on the inside to be done, no program, no meeting, no sponsor, no nothing is going to work.”

But painful, wearying reminders are everywhere of how hard it is to make that change last, no matter the resolve.

“I hope one day they will see and say, ‘OK, my mom was 48 years old, and she got clean, and she stayed clean,’” Redina said as we drove down the highway that October morning. “That’s my biggest goal in the world, is to have my children see me as an inspiration for getting clean and not a failure.”

Nov. 14 marked one year since Redina was released from prison and, in some ways, she is even further away from achieving her goals now than she was then.

She’s only been off drugs and alcohol for a few months and, for the foreseeable future, the chance to raise her youngest daughter is off the table.

She’s still living at the recovery house and is now working as a receptionist for a company that sells used car parts. Although she’s relapsed twice this year, she hasn’t been arrested again, and she’s back on Vivitrol.

She’ll be on parole until 2027, when she’s 59.

—

WHYY is one of 15 news organizations in the The Reentry Project, a solutions-oriented focus on the issues facing formerly incarcerated Philadelphians. The aim is to produce journalism that speaks, across the city and across media platforms, to the challenges and solutions for re-entry.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.