More Philly overdose patients turning down ambulance ride after naloxone

'It’s a near-death experience, and you really want to get these people the help they need,' says the Philadelphia Fire Department's head of emergency medical services.

Listen 5:03-

A water bottle is filled with needles at an encampment beneath an overpass at Emerald and Lehigh Streets. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Many drivers honk horns and yell out their windows to people living under the overpass at Emerald and Lehigh Streets in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

People living under the overpass at Emerald and Lehigh Streets in Philadelphia are removed weekly, but return after city workers complete the clean-up. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

During he spare time, Rosalind Pichardo brings food, clothing, and clean needles to people living beneath an overpass Emerald and Lehigh Streets in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

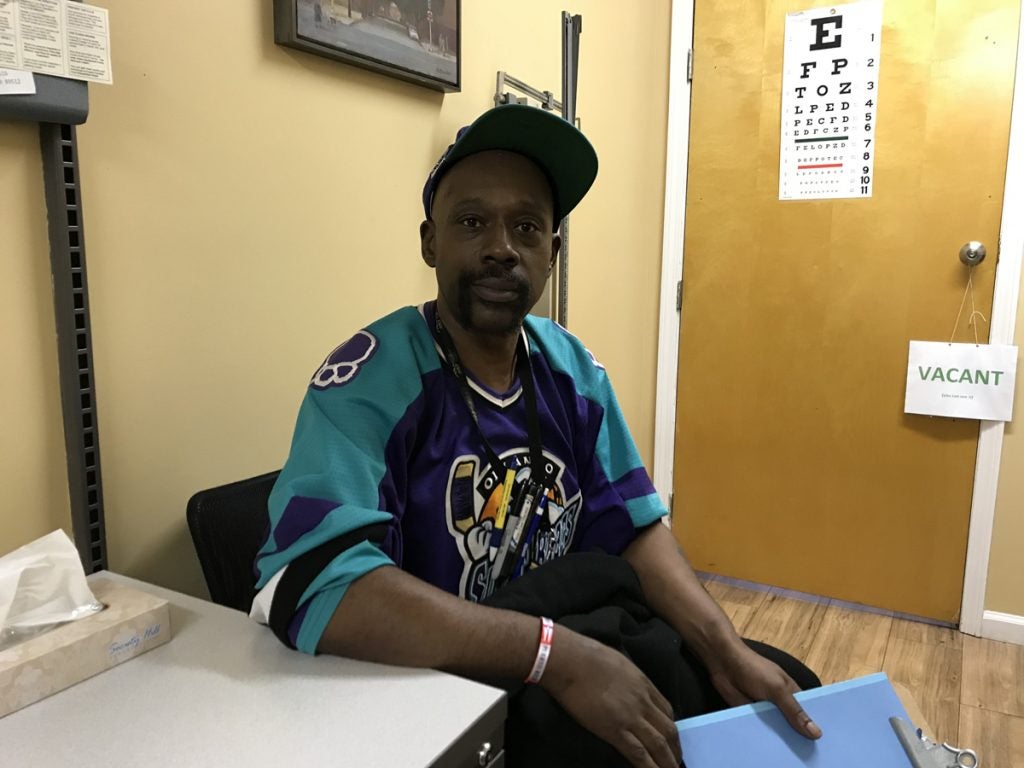

Dante Jones was revived with Narcan during an overdose by his girlfriend. He said he wouldn’t go to the ER because of the judgement of those working at the hospital. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Needle caps mingle with gravel in the secluded alleyway behind Genevieve Geer’s house in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, orange plastic pebbles that speak to its popularity as a place to inject heroin.

One day in August, Geer and her husband saw a man lying on the ground outside their back gate. A woman was leaning over him in a panic.

“He was turning kind of purple; she was screaming,” Geer recalled.

An ambulance arrived with the overdose reversal drug that could save his life.

“They jabbed him with the Narcan,” Geer said. “He took a great big, deep breath and looked stunned.”

When the man came around, Geer says the paramedics asked him a list of questions, including whether he wanted to seek addiction treatment and get checked out at the hospital. He said no, and soon his rescuers got in the ambulance and drove away.

Not long after they left, Geer says, the woman he was with started rifling through a purse.

“She pulls out needles,” Geer said. “Then they moved a little further down the street, and then they shot up again.”

A dangerous cycle

Paramedics in Philadelphia revive thousands of people from overdoses each year. After they come around, more and more drug users are refusing an ambulance ride to the hospital. According to the most recent data, 16 percent of the patients Philadelphia paramedics revive with the opioid-overdose antidote naloxone refuse a ride to the hospital. That’s three times as many as just two years ago. The climbing refusal rate could make it even tougher to get drug users help for their addiction.

Paramedics try to get every overdose patient into the ambulance, said Jeremiah Laster, the head of emergency medical services at the Philadelphia Fire Department.

“It’s a near-death experience, and you really want to get these people the help they need,” Laster said.

Laster says people revived with Narcan — the brand name for a device that delivers naloxone — need monitoring to make sure they don’t fall back into an overdose when the medication wears off.

Skipping the ambulance ride could also mean missing an opportunity to start treatment. Hospitals throughout Philadelphia and the state are working on “warm-handoff” programs to make emergency rooms better access points for detox beds and medications that help users get clean. The idea is instead of just handing people written information about treatment options, before they leave the ER, they get connected to a real person offering treatment. But if overdose patients don’t get to the ER, they miss that opportunity.

“It’s a difficult thing, but you can’t force the care on people,” Laster said.

Laster says Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney’s opioid task force considered making hospital runs mandatory. But that was controversial, and it didn’t make the final list of recommendations.

‘My overdose actually saved my life’

So why are more and more patients refusing to go? Laster thinks it has something to do with the greater number of overdoses paramedics are responding to these days.

During the first half of 2017, Philadelphia paramedics administered naloxone more than 3,000 times — close to twice as many as the same period last year.

The medical director of the city’s emergency medical services says there’s also a “growing awareness” among drug users of the withdrawal symptoms that follow a hit with naloxone and how many hours they might be stuck in the ER. A lot of people paramedics are saving these days already know the drill.

Lewis Brown has overdosed three times in his lifetime, and he was revived by paramedics each time.

He’s now in recovery and does outreach work for the harm reduction nonprofit Prevention Point Philadelphia. But the first time Brown overdosed, he was living out in the cold in an abandoned building.

“I didn’t want to go to the hospital and the paramedics was like, ‘You got a lot more going on, you should go to the hospital,’” Brown said.

He listened to them, and spent four months in a hospital bed recovering. It turned out he had pneumonia.

“My overdose actually saved my life,” Brown said.

But after the second and third overdoses, Brown said no to the ambulance. The withdrawal symptoms were too much to bear.

“Diarrhea, throwing up, nose snotting, cold shakes, you know, you don’t want to feel that,” Brown said. “So, instead of going to the hospital and getting more treatment, I went and got more heroin. The same thing that just almost took my life, I ran right back and got again.”

Prevention Point’s associate executive director, Silvana Mazzella, says it’s important to tell overdose survivors that the withdrawal symptoms are a temporary effect of the naloxone, and that it’s not safe to use again. At its Kensington headquarters, Prevention Point often monitors those who refuse the ambulance ride until they’re out of the woods.

The reality is that, right now, in spite of the push for warm-handoff programs, many hospitals don’t do that much more for them, Mazzella says.

“You might get offered treatment,” she said. “That treatment will likely not be available right away. Someone is in withdrawal after that reversal. So, if they are waiting several hours for that treatment assessment, it’s unlikely that someone’s going to stay.”

Mazzella says that until hospitals streamline the treatment handoff, overdose survivors who have gone to the ER before will be more likely to walk away from paramedics.

Deploying outreach after emergency

To address this, fire department officials are talking with Prevention Point about having outreach workers such as Brown visit people who decline an ambulance ride.

“When 911 gets there, if John Doe doesn’t want to go to the hospital, perhaps somebody else can walk with him and talk with him as he decides what he’s going to do next,” said Laster.

Laster says it could be an effective way to broach the topic of treatment.

But, as of now, that idea is just another work in progress.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.