In Pennsylvania’s 16th district, urban centers grapple with dominant outside interests

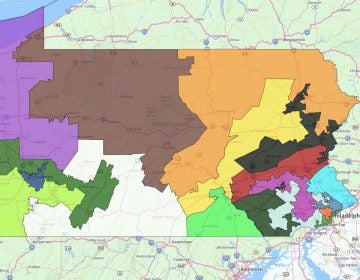

Listen 5:27In the interactive slider above, the city of Reading can be seen as an appendage thinly sewn to the top of Pennsylvania’s 16th congressional district.

Reading Mayor Wally Scott, a Democrat, has decided to focus on things he can change without relying on higher levels of government.

“I don’t have any reason to need them for anything,” he said.

So far his priorities have boiled down to four things: trash, parking, water and police.

“I live here,” he said. “I don’t want to live in filth, in trash. And we were sending people to jail for victimless crimes.”

Looking at Pennsylvania’s congressional map, it’s not surprising that Scott thinks this way.

The city of Reading has long felt out of place on the U.S. congressional map. It used to be divided between two different congressional districts.

Since 2011, it’s been in one, but the city has been separated from its surrounding communities in Berks County, and attached by a small sliver to rural Lancaster County.

Compared to the rest of the 16th congressional district, Reading is clearly an outlier.

It is Pennsylvania’s only majority Latino city, one where nearly half of residents were born in another nation.

The city is also one of the nation’s poorest, with a 40 percent poverty rate that more than triples the rate in the district overall.

And Reading’s homeownership rate (36 percent), percentage of people who’ve completed college (9 percent), median household income ($27,000) and value of owner-occupied houses ($68,000), are also less than half the rates seen in the 16th district.

The changes to the 16th district’s boundaries are generally viewed as part of a larger effort to advantage the GOP as part of a gerrymandering scheme that’s thought to be especially egregious in Pennsylvania.

The constitutionality of Pennsylvania’s congressional map is currently being questioned in state and federal court. But gerrymandering attempts are currently considered legal and have been utilized since the 1800’s by the party in power.

Republicans have controlled the Pennsylvania legislature and, thus, the mapmaking process during last two rounds of post-census redistricting.

In the 16th, the GOP’s victory margins have actually narrowed steadily over past two decades to their thinnest ever (54 percent) in the 2016 election, the first since 1996 without 10-term incumbent Republican congressman Joe Pitts in the running. These results could, however, be fully expected — a carefully calculated attempt to ensure a win there while securing seats in other, more competitive districts.

Given this situation, it’s understandable that Scott, a retired local judge, might trust his energy is better spent on things over which he has more direct control. He says he eschews politicking, but has witnessed the dysfunction first hand in his limited dealings with state lawmakers in Harrisburg.

“It’s the Democrats who blame Republicans, and then it’s the Republicans who blame the Democrats,” Scott said. “Why are you worthwhile if you can’t cross over and talk to somebody on behalf of human beings and forget about the political parties?”

Maintaining status quo

Freshman U.S. Congressman Lloyd Smucker, a Republican, now represents the 16th district. He hosts office hours every other week in Reading’s City Hall in a room that shares a wall with the space where Scott has his own office hours.

On a recent morning, Scott had about two dozen people waiting for him — about four times as many visitors as the Congressman’s office generally gets over the course of an entire day.

One person waiting for Smucker was Rev. Evelyn Morrison. She says she and other community ministers would meet quarterly with Smucker’s predecessor, but that she hasn’t seen the new congressman since his campaign last year.

Morrison grew up in Reading and attended Alvernia College. Now in her 60’s, the pastor is a fixture at meetings of city council and the local water authority, contributing in recent years to public pressure that led to a forensic audit of the authority and its executive director resigning.

“Without the voice of the advocate, all this stuff would have been under rug. We have to participate. You have to be engaged in order to understand what’s happening here,” she said.

Morrison, who ran as a Republican last year for the state legislature, was called in short order by one of Smucker’s staffers to the office. It’s big enough for a desk, two chairs and not much else.

She quickly learned Smucker wasn’t there. To see him, she’d have to make an appointment through an online portal.

So, she left without getting into the issues she wanted to discuss, including congressional redistricting, which will happen again after the 2020 census.

“It’s the older politicians who’ve have been in position for a long time wanting to maintain their status,” she said.

Morrison also thinks one of the many negative effects of gerrymandering is its impact on younger adults in particular, discouraging them from civic engagement.

“All that effort, all that money, … and it didn’t matter”

Troy Turner, 26, is not one of those disenfranchised youth.

“It’s so important to be out there, doing whatever it takes — whether it’s a lobbying, whether it’s disrupting certain events,” he said. “Anything it takes to … hold them accountable.”

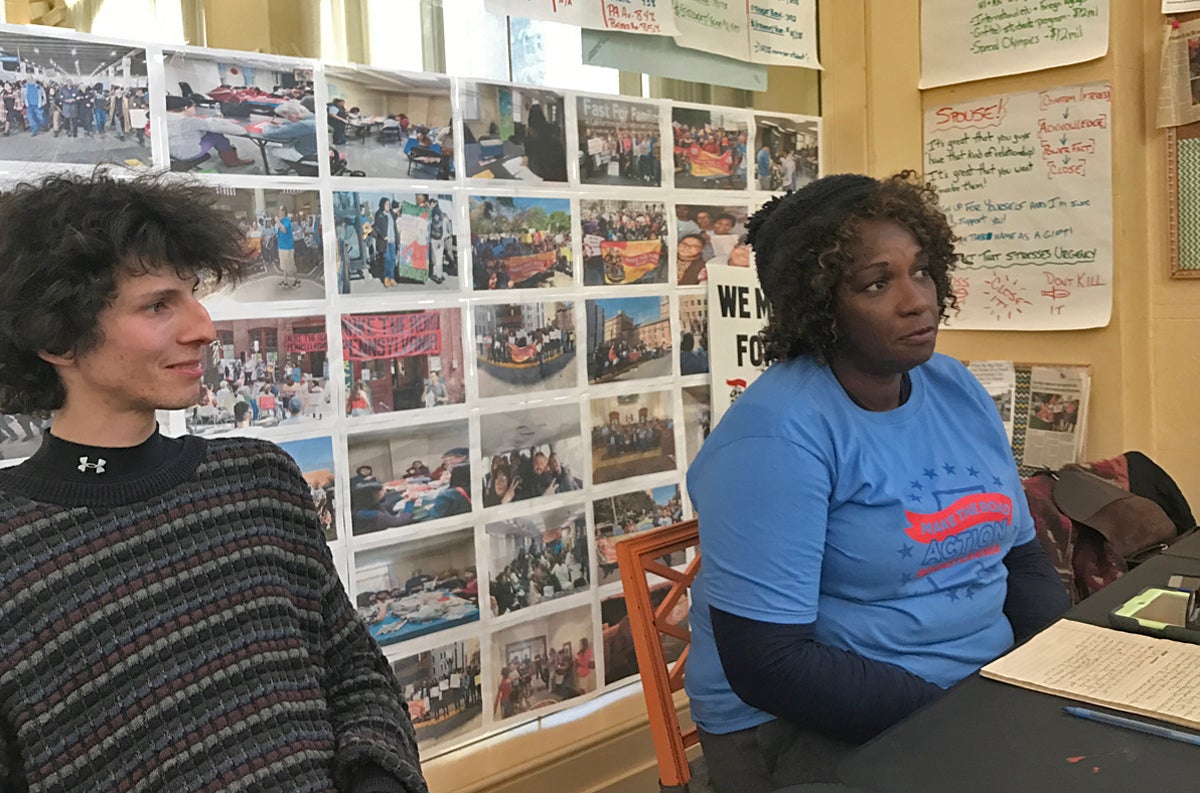

Turner grew up outside of Reading and lives in the city now. He also works there, as a field manager for Make the Road Pennsylvania, a local advocacy group focused on empowering Latino immigrants.

Turner says he does see a lot of frustration, people thinking their votes don’t count. They’ve experienced candidates they support who win and then abandon their promises. And then there’s what happened during the last congressional election: the Democratic candidate garnered way more votes in the city of Reading, but lost the election in the 16th district handily.

“We canvassed the entire city, knocked on 55,000 doors, had record turnout in all the precincts we were active in … and it still didn’t make a difference as far as the district is concerned,” he said. “We put all that effort, all that money, all these people into doing that. And in the grand scheme, it didn’t matter – or, I should say, it didn’t make a difference.”

But he says people haven’t given up about issues that affect them directly.

“It kind of helps with some of those feelings of hopelessness,” he said.

Diluted perspective

The second largest city in the 16th district is Lancaster, a 40-minute drive through farmland from Reading.

The Red Rose city, as it’s known, has never been gerrymandered, like Reading has; it’s never been cut in half — or cut out of its surrounding county.

But it shares little in common with its outlying suburbs and farms. And in that way, it’s akin to Reading.

The interests and issues of Lancaster, pop. 60,000, are often diluted by the residents of Lancaster County, half a million strong and the dominant community of the 16th.

Kevin Ressler, who runs the Meals on Wheels program in Lancaster, sees this pattern repeated statewide with widely dispersed small cities.

“You just have these significant pockets of populations dominated by the suburban perspective,” Ressler said.

But Ressler, 33, doesn’t have an easy fix.

“I don’t think you’re going to able to draw lines that are going to perfectly dictate that the representative is going to represent all the different pockets that exist for our country or state,” he said.

But he also believes gerrymandering works, in part, because some voters conform to demographics-based expectations that they’ll stay home, vote against their interests, or go with a candidate mainly because they feel familiar or comfortable.

And it goes both ways.

“You talk about Republicans suppressing the vote,” Ressler says. “The Democrats don’t really want everybody out there voting either. The more votes, the more risk. And they are about maintaining power.”

Ressler lost a bid this year to become the Democratic candidate in Lancaster’s mayoral race.

The current mayor, Democrat Rick Gray, will retire in January after completing three terms.

“The 16th congressional district looks like a pair of pliers or something,” said Gray. “It’s crazy. It’s pathetic. We don’t have enough in common with the rest of the district. We have different problems. We have different demographics. And really in my opinion there ought to be a nonpartisan group that puts together districts.”

Smucker, who helped create the current congressional district maps as a state senator, doubts that will yield a fairer map. He says he’s open to changing the redistricting process, but he doesn’t believe that taking it out of the hands of the legislature will make the result less political, even with an independent commission.

“Most people would want someone who’s accountable to the people to make decisions that affect district lines, so I think you’d want elected officials to have some degree control over the process,” he said. “And, of course, that’s the way it’s always been done.”

As for the way the 16th was drawn, he says multiple factors came into play, including politics. But Smucker, who was born and raised in Lancaster County, likes the diversity of the district he now represents and says he’s working diligently to know all of it — citing over 100 visits to schools, businesses and other organizations during the past 10 months.

“People can contact our office at any time, and they do. There are tens of thousands of contacts we’ve responded to, whether that’s email or phone calls,” he said. “And that, of course comes from all over the district.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.