One woman’s mission to make sure everyone carries Narcan — including drug dealers

In Kensington, Rosalind Pichardo learned, people using drugs usually want to have Narcan on hand. Drug dealers were tougher to convince.

Listen 9:27

Rosalind Pichardo, an outreach worker in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, has reversed 400 overdoses by her own count. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Once a week, Rosalind Pichardo loads up a shoulder bag full of cookies, clean socks, unused syringes and Narcan and hits the streets of Kensington — the neighborhood at the heart of Philadelphia’s overdose crisis.

Despite its proximity to Center City Philadelphia, Kensington can feel as if it operates by a different set of rules. People use drugs and sell drugs in parks and on street corners and front porches. Shopkeepers sweep garbage and used syringes from the sidewalk in front of their stores, which sell cellphones or appliances or tires. Longtime residents come and go from the screeching El train overhead; kids step over syringes on their way home from school.

Pichardo grew up there, but it was only recently she turned her attention to the overdose crisis. For many years, after two of her siblings died of gunshot wounds, she offered support to families who lost loved ones to gun violence. She never felt like her family got the help they needed afterward, and she wanted to assist others.

Over time though, Pichardo noticed gun violence was not the only epidemic plaguing the streets of the neighborhood. One day, she was handing out food to people who were homeless — a good deed she described as a “break” from the emotional demands of her survivor support work. While doling out snacks, she saw a man lying on the sidewalk begin to turn blue. She didn’t know what was happening — she thought he might be choking.

“I was naive,” Pichardo remembered. “I knew people did drugs around here, but I didn’t know what an overdose looked like.”

She learned overdoses were happening everywhere: People were dying at alarming rates. So when Pichardo found out there was a nasal spray that could reverse overdoses, she started giving out as much as she could.

Now, she has relationships with a lot of the people using drugs and living on the streets of Kensington. She calls them her “sunshines,” because she wanted a word other than “addict” that avoids the negative connotations many have about people who use drugs. There wasn’t really a good alternative, so she made one up.

“Hey, sunshines!” Pichardo hollered toward a group of people huddled together on Allegheny Avenue mixing heroin — more likely, some combination of heroin and fentanyl — with water to prepare to inject it.

Each of them turned in response, and several waved as she approached.

“Y’all good with Narcan?” Pichardo asked.

“How much is it?” asked one man. Surprised he would think that she was charging, Pichardo chuckled.

“It’s gonna cost you a hug!” she joked. Everyone laughed, and Pichardo left the man with an embrace and a box of naloxone.

Pichardo doesn’t just give out Narcan, she also uses it. A lot. She’s reversed hundreds of overdoses, tracking them in a little black book she keeps in her fanny pack.

Narcan works to reverse the effects of opioids by restoring oxygen flow to the brain. It’s administered using a nasal spray, and is most effective when combined with rescue breathing and chest compressions, which Pichardo performs on hands and knees.

During the pandemic, that type of work has been harder — in fact, Pichardo contracted COVID-19 in April, though she doesn’t know exactly how. Once she recovered, she was back on the street, reversing overdoses using a special air bag to avoid mouth to mouth contact. Sometimes, it will take more than one dose to revive someone.

Who should carry Narcan?

One particular reversal changed the way she thought about who she should be giving Narcan, Pichardo said. A man was overdosing in front of a line of people waiting for free samples a drug dealer was handing out — a common practice to get people to come back and buy more.

Pichardo rushed to the man’s aid and gave him Narcan — her last dose. But he remained unresponsive. She reached for her phone to dial 911 and request an ambulance with more Narcan. When the dealer, who had been continuing to hand out samples, saw her calling the authorities, he pulled out a 9mm handgun.

“He put the gun to my face and said, `No, you’re not gonna call. Cause I’m not done handing out these samples.’”

Pichardo convinced the dealer to help her roll the man who was overdosing onto his side, so he wouldn’t choke on his own saliva. But he remained unresponsive, and she was paralyzed with fear. She wanted to rush home to grab another dose of Narcan, but that would mean returning to the man who had just threatened her life.

Thankfully, after a couple of minutes, the person who had been overdosing came to, and survived.

A few days later, Pichardo went back to where the dealer had been handing out samples, to track him down. She wanted to give him some Narcan.

“Now, we’re semi-friends, where he asks me for Narcan,” said Pichardo, laughing to herself. The dealer texts her when he runs out of doses, and she drops a big bag of it off on his porch. “It’s the strangest relationship you could ever have with a person,” she said, laughing. “I’m like his Narcan dealer, I guess.”

At WHYY’s request, Pichardo asked her friend if he would be open to an interview, but he declined.

Subscribe to The Pulse

‘No one should die of an opioid overdose’

Ever since that day, when Pichardo makes her rounds to hand out Narcan, she doesn’t just give it to people using drugs. She figures she might as well offer it to people dealing, too.

“If they’re business-savvy, they definitely want their customers coming back, right?”

If that idea seems kind of fringe, so did the notion that drug users would ever carry Narcan themselves. Naloxone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to reverse opioid overdoses in 1971, but it was really only used by doctors and paramedics for the next 20 years.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s, during the height of the HIV epidemic, that harm reduction advocates started thinking seriously about shifting naloxone out of the medical realm and into the hands of drug users themselves. By that time, syringe exchanges had begun to prevent many people who use drugs from contracting HIV. That meant that the more pressing, lethal threat for drug users was no longer HIV, it was overdosing. But back then, giving naloxone to people injecting drugs was a very controversial idea.

“Harm reduction was a dirty word in the federal government,” said Nancy Campbell, a researcher at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the author of a book about the history of naloxone.

Campbell writes about naloxone as an “act of civil disobedience,” noting examples of people historically breaking the law in efforts to distribute it and save lives. Naloxone was considered drug paraphernalia in some places — you could get arrested if you were found carrying it. The thinking was if you knew you could reverse an opioid overdose, that would encourage people to use drugs.

Harm reduction advocates think about it the opposite way. As they see it, people suffering from addiction are going to use drugs regardless, so if there’s a tool to stop someone from dying, that tool should be easy for anyone to get and use.

Campbell wrote about a small community of drug users in the hills of New Mexico, who learned about naloxone when paramedics would come out there to reverse an overdose. They wanted to keep some on hand and save the EMTs a trip, so they offered the paramedics a bargain: In exchange for leaving some naloxone behind, the paramedics could take with them their own personal supply of locally grown marijuana. According to Campbell’s account, they struck a deal.

After a decades-long battle, naloxone is now pretty mainstream. Forty-six states, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, have waived the need for a prescription, so anyone can purchase doses at a pharmacy. Public health departments distribute naloxone and train people how to use it.

The way Campbell sees it, drug dealers handing out Narcan with fentanyl is no different than a doctor co-prescribing naloxone if they prescribe an opioid for pain — it’s the same principle, operating in an illegal economy. Campbell said putting Narcan in the hands of dealers is consistent with its historical role on the cutting edge of harm reduction.

“Narcan has gotten into the hands of dealers, and I believe that is a good thing,” she said. “Those are going to prevent largely preventable deaths. No one should die of an opioid overdose.”

Pichardo has no trouble giving naloxone to people who use drugs, but the dealers can be a bit more skeptical. She has a whole strategy for how to approach them, and like any good plan, it revolves around snacks.

She carries packaged cookies — Oreos are the most popular — that are hard to refuse.

She starts by offering food to her “sunshines” — that signals to people that she’s an outreach worker and she’s there to help. Then, she’ll offer snacks to the dealers. Some will accept, and that’s when she’ll ask if they carry Narcan.

“Some will say yes, some will say no,” Pichardo said. “The ones that say no, I guarantee that maybe by next week, someone will carry it.”

Pichardo said it’s easier to convince people to carry Narcan if she recognizes them from around the neighborhood. But after a police sweep of the area, she’s less likely to recognize the faces of those dealing drugs — when people are locked up, a new crew pops up to take their place. Though sometimes, even the new people go for it.

For Pichardo, whether she is talking to someone using drugs or selling drugs, her goal is the same.

“It’s always been in my mind to meet people exactly where they are,” she said. “I’m not trying to change anybody, I’m just trying to make people smile for a moment. I think I do that a lot.”

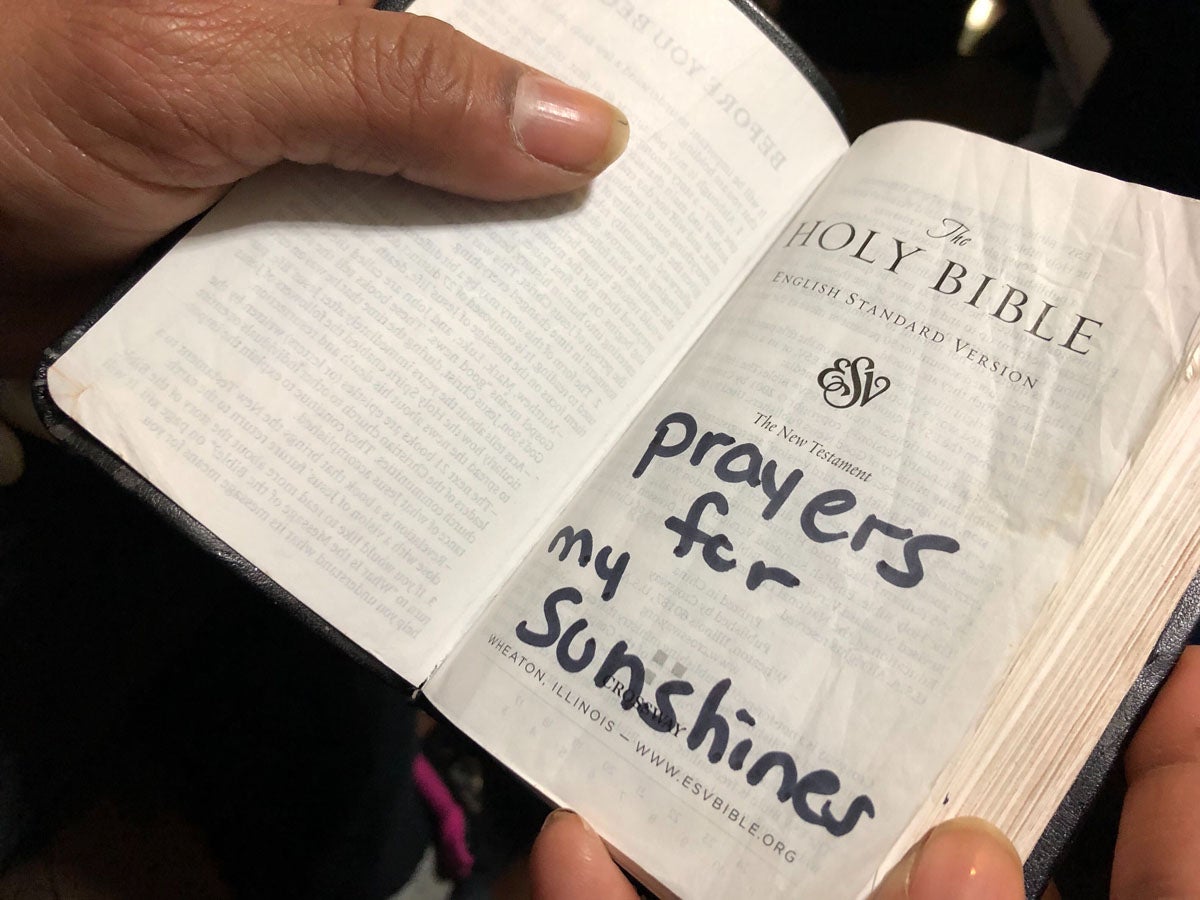

Still, the work is emotionally draining. She relies on her faith to get her through. The little book Pichardo carries with her to track the overdoses she’s reversed is actually a pocket-sized Bible. Across the thin pages and fine print, she’s jotted down, with a Sharpie marker, the rough demographic information of each person she’s saved.

One entry reads: Male, July 12th, 2019. Male in his 60s, Kensington and Somerset. Two narcans to reverse him — he went to the hospital, the stamp on the bag was Venom.

Pichardo would like to pray for the people whose lives she’s saving, but she doesn’t always feel that hovering over someone while reversing an overdose is appropriate.

“They gonna be like, `Lady, you crazy!’” Pichardo said. Instead, she notes details about them across the Bible verses. “They don’t even have to know you praying for them — just write it in the book, and that’ll be my way of praying.”

As usual, she’s just trying to meet people where they are.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.