One doctor’s mission to recycle pacemakers for patients in India

Listen

Cardiologist Daniel Mascarenhas says life saving items like pacemakers cost $6

A Pennsylvania doctor is turning medical trash into life-saving gold.

It’s not every day that I discuss the best way to evade customs, but today, that’s exactly what I’m doing.

“So I’m going to pack them up and send them with him,” says Dr. Daniel Mascarenhas. “And I’m going to tell him how to carry them, because if you put them in the middle of the suitcase they can look like a bomb because they’re closed circuit. You just put them on the side because on the side you cannot see them.”

I should clarify here. We’re not talking about bombs, or drugs. We’re talking about pacemakers and Dr. Mascarenhas is a cardiologist. And believe it or not, we’re talking about saving lives. Let’s take a step back.

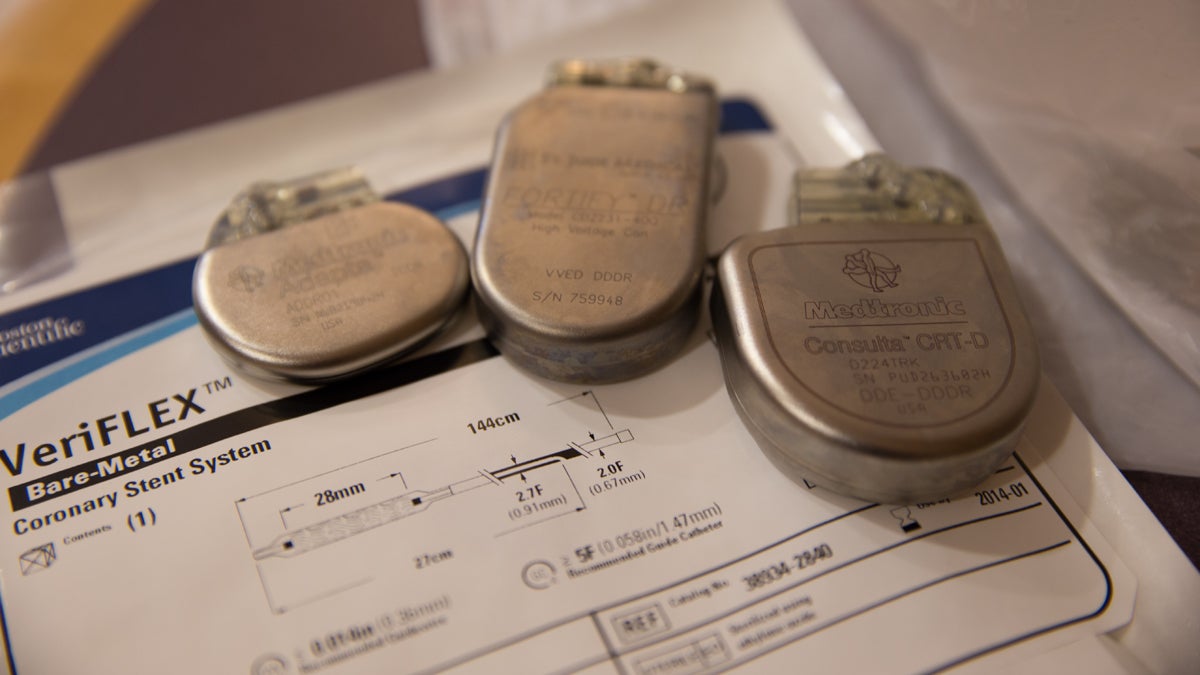

A pacemaker is a nice computerized device that goes under the skin just below the left side of the breastbone, and is hooked up to the heart through two wires. They are small devices that kind of look like metallic peppermint patties and they have one job: to keep a failing heart beating. Every year about a quarter of a million people receive pacemakers in the United States, but Mascarenhas is originally from India, and over there that number is much smaller. It’s somewhere closer to 15,000.

But what happens to all the people in India that aren’t getting pacemakers?

“In India really, there is no safety net. So if you don’t have the money, in short, if you’re from the slum, you’re dead,” he said matter-of-factly.

You need a lot of money, too, because a pacemaker costs $6,000, and if you need a defibrillator, that costs $28,000. The fact that life-saving devices are out of reach for many Indians isn’t a surprise for Dr Mascarenhas, after all, he grew up and trained there. But there was something about the pacemaker industry here in the United States that did surprise him.

“One of my patients had a pacemaker and she died,” he remembers. “They put in a pacemaker and two days later, she was dead, and they buried her with the pacemaker. That was an eye-opener for me. What a waste of resources. Something costing $6,000 was buried in the ground.”

Pacemakers come with a 10-year battery life, give or take, but the question most of us never thought to ask is this: “What happens to the pacemaker when the patient dies?”

Well, it turns out that the device is buried with the patient, still fully functional, still ticking away, trying to beat a dead heart. And this could go on for years after the body has decomposed. It’s kind of morbid.

“The sad part is that we could reuse them in this country by re-sterilizing them,” he says. “But nobody wants to do this because we are a land where we learn to waste.”

Recycling life-saving devices

So Dr. Mascarenhas came up with a scheme.

“I call up the funeral homes,” he shrugs. “Every week, when I have nothing better to do, instead of golfing, I call up the funeral homes, find out if they have devices.”

If they do, he asks permission from the family to remove the device from the body.

“I take them home, I put them in a Cidex solution and I clean them up,” he says.

Then he measures the remaining battery life on the device, in hopes that there will be at least 5 years left on it.

“And then once I do that, I put them in a package and send them to India,” he says.

But he can’t just put them in the mail because they could get stolen along the way or they could end up in the hands of customs.

“So anybody who tells me that they’re going to Mumbai, I stop them and ask them, ‘Can you carry this for me?’ There’s this doctor who comes and picks them up. They get completely gas sterilized prior to using them. So, if I’ve used it in a patient who can’t afford it, and who has still 5 years left to go on that battery, he can start planning for the future. I’ve had it all well thought out.”

Exploring the legality of his mission

There’s just one catch, this whole thing isn’t exactly legal.

“The FDA regulations are ‘single use only,'” he says. “[It’s] illegal if I use it in this country.”

I wondered why it’s illegal in this country to reuse these expensive electronic devices. I mean, people buy refurbished laptops, people buy refurbished iPhones, why can’t you have a refurbished medical device?

“If you put the refurbished iPhone in your body, then that won’t be legal,” he says. “Simple as that.”

That’s because, even though Dr. Mascarenhas follows the sterilization process to the letter, the FDA can’t guarantee sterility once the device has left the factory, and an implanted device that gets infected can be catastrophic for a patient. In India, the laws surrounding this are a little bit looser. That is to say, it is technically illegal to reuse devices, but so far enforcement seems to be low.

“We get a consent from the patient that there is a small chance of infection,” he said. “That’s not the end of it, after the device is obtained, they need to send me a letter that they got this device free.”

‘It’s not always a rosy picture’

Over the years, Dr. Mascarenhas’ project has steadily grown.

“It’s not only with devices, now I’ve graduated from cardiac to gastrointestinal endoscopic surgery, to laparoscopic surgery, to orthopedics, wherein I collect devices which normally would have been thrown away because their shelf life has expired. But really they have not expired. And we’ve used them in India. Because one man’s trash is another man’s gold.”

So that’s the position Dr Mascarenhas finds himself in. To do something that seems so common sense, he has to essentially become a graverobber, then a smuggler and only then a doctor.

“And believe me, it’s not always a rosy picture,” he told me. “This was in January of 2003 wherein by mistake I went through the wrong area in customs and they impounded my bag. They took all the devices.”

But, despite occasional setback, for Dr. Mascarenhas, it’s worth it.

“I could find a diamond worth $5,000, but that wouldn’t stimulate me as much as finding a device which has 10 years,” he smiled. “Because the diamond is not going to give somebody life.”

Is this practice ethical?

We checked in with NYU medical ethicist Art Caplan on this issue, who says he is generally not opposed to reusing medical devices. However, he says this is not a good idea when done in a “mom-and-pop” style of operation.

Too many things could be going wrong in the sterilization process. The medical device could be compromised in some way the doctor is not aware of. True patient consent in India can not really be verified. He said reuse of medical devices should be guided by strict procedures and guidelines.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.