Off the battlefield, many veterans face a new foe: damaged hearing

Tinnitus is the most common service-connected disability, the VA says. More than 2 million veterans get compensation for it.

Listen 06:39

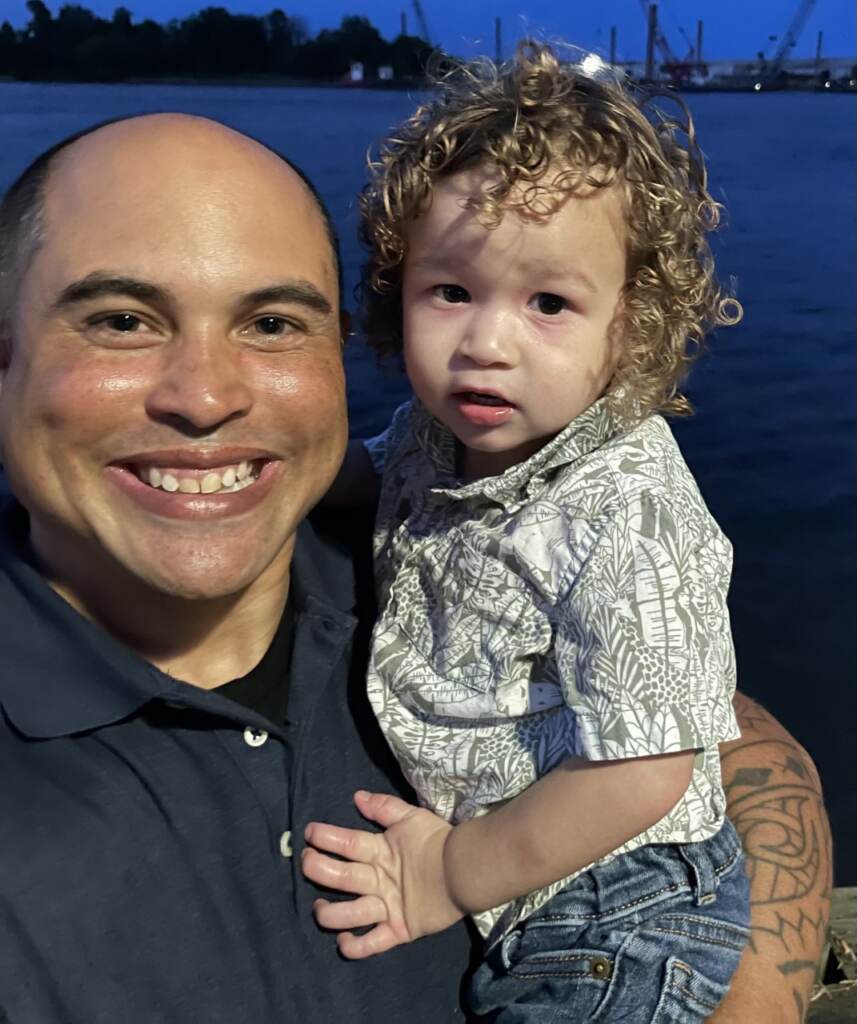

Dave Schible suffers from tinnitus and hearing loss. Tinnitus is the most common service-connected disability, the VA says. More than 2 million veterans get compensation for it. (Courtesy of Dave Schible)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

When Dave Schible thinks of the things that destroyed his hearing, one memory rises to the surface: an explosion on Nov. 24, 2004, during his first deployment to Afghanistan, as a sergeant and fire team leader in the U.S. Army.

“It was so loud and so horrifying that it’s just really hard to describe,” Schible said. “It felt like it went in slow motion. I was looking at the vehicle, and all of a sudden it was just dust and smoke, and just debris hitting our vehicle.”

The explosion killed two men, missing him by just a couple of feet. The experience, and others like it, left scars not only on Schible’s psyche, but on his hearing.

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, tinnitus is the number one service-connected disability veterans deal with. More than 2 million veterans receive compensation for tinnitus, a ringing or buzzing in one or both ears — and the numbers are growing.

In addition to tinnitus, research has found that hearing loss commonly occurs in the wake of traumatic brain injuries. There are other auditory complaints, too. As many as 48% of veterans with blast exposure suffer from decreased sound tolerance, meaning they have negative reactions to everyday sounds, and can easily be overwhelmed by background noise.

Schible got his first inkling of the damage explosions could do to his hearing during basic combat training.

“[The instructors] set a mine off, and it was like, ‘Oh my gosh, that is ridiculous,’” Schible said. “And my question was to them, ‘What’s the significant damage that these Claymore mines can do?’ A lot more damage than you think.”

Schible said he and his fellow soldiers did receive hearing protection devices.

“The situation dictates, right?” he said. “When we’re getting shot at or when things happen in theater, we can’t just go tell the enemy, ‘Hey, cease fire — wait till we put our hearing protection in.’ Things are going to happen suddenly, and we can’t help that.”

There were improvised explosive device blasts and firefights that Schible estimated exceeded 130 decibels — well into the danger zone when it comes to hearing.

It was during that first deployment to Afghanistan that Schible noticed problems with his hearing. But he didn’t realize the extent of the damage until he’d returned home and was going out for the Special Forces — a dream he’d had for years.

“The Special Forces recruiter said, ‘Hey, I really want you on our A-team — however, you failed your hearing test,’” Schible recalled. “‘You need to go back, and I can’t give you a waiver. I can’t clear you.’”

So Schible took a second hearing test. This time, the results were unequivocal.

I was told, ‘Sergeant, we are going to issue out a set of hearing aids. You’ll probably be separated out of the Army within the next five years, and you’re non-deployable,’” Schible said. “And that’s how I realized this is a very severe issue.”

Schible was devastated. His whole life was centered around the Army. In fact, it was a family legacy — he’d first joined up in 1998, at the age of 19.

“My dad served 20 years in the United States Navy, and he retired as a chief,” Schible said. “You know, watching him succeed and watching other service members defend this great nation, I felt like I wanted to be part of the team.”

But just eight years in, Schible found out that his expiration date had already been stamped. His mind swirled around the news.

“I remember thinking to myself, ‘Well, what do I need to do next?’” he said. “‘And how am I going to go about it? Am I ready to get out of the military? Am I going to disappoint my dad? Am I going to disappoint everybody that looks up to me?’”

On top of all that, at the time Schible was going through a difficult divorce. The last thing he wanted was to sit at home while all his buddies deployed. So he volunteered for another tour — and made sure this time that his damaged hearing wouldn’t stop him.

“The funny story is, I didn’t get cleared to get deployed,” he said. “The lady who was stamping the form turned her back. I stamped it, and I left quickly.”

Schible turned in the stamped form and was approved for a new deployment to Iraq.

“Yeah, that was probably one of the most illegal things I’ve ever done,” he said.

It would end up being Schible’s final tour. After returning, he spent another few years as a drill sergeant, before finally being separated out for good because of his hearing.

Today, he uses bilateral hearing aids, but the damage remains undeniable and irreversible.

“The tinnitus is the worst — when everything is so quiet and you’re really trying to concentrate,” he said. “That is the worst time.”

Usually, he uses static from his hearing aids to drown out the piercing tone — but it doesn’t always work.

“When I try to go to sleep at 8 p.m., I end up going to sleep at 11 or 12 because it just sounds so unbearable,” he said.

Schible also struggles when talking to other people in noisy environments.

His first job after leaving the Army drove that problem home. Working as a barista at Starbucks. Schible would struggle to hear what customers were saying over the din of music and blenders.

When customers got frustrated, he’d explain that he had hearing loss.

“I was told, ‘That’s not my problem — give me my order,’” Schible said.

Years later, he’s on the other side of the counter. But that doesn’t make his interactions much easier.

“So when I ask somebody, ‘Hey, can you repeat yourself?’ And it’s not for the second time — it can be a third or fourth or fifth time,” he said. “You can see it on their faces that they’re disgusted. They don’t want to repeat themselves. You can see them getting frustrated.”

Interactions like these are common for people who are hard of hearing, Schible said — and can not only affect their interactions, but how they feel about themselves.

“Sometimes, you just kind of want to hide yourself and just really not go out in public,” he said. “Folks like myself who get flustered after so long just don’t want to really talk to people in general.”

Experiences like these have led Schible to become an advocate for veterans with hearing loss.

“There’s really not enough attention [on the problem],” Schible said, adding that isolation is a major problem for veterans with hearing damage.

“Folks with any type of disability always feel like they’re different,” he said. “Difference meaning, ‘No one’s going to accept me for who I am. No one’s going to really care about me … want to talk to me because they have to repeat themselves 9 million times.’”

There’s no cure for profound hearing damage — and Schible said a lot of veterans are too proud, or too ashamed, to take advantage of things that could help, such as hearing aids.

They can struggle to work, or interact with other people. On top of that, the military gives little compensation for hearing loss.

All of it adds up: For some veterans, it can lead to alcohol and drug abuse, even thoughts of suicide.

“They feel worthless — they feel like they’re a failure,” Schible said. “And that’s where we have to intervene and say, ’Hey, look — I cope with the same thing as you, but I don’t think about getting down to the bottom of the bottle. I don’t feel like I have to drink 24-packs of beer.’”

What you have to do instead, Schible says: “Stay busy.”

These days, Schible is busier than ever.

He’s currently vice president of the Hearing Loss Association of America’s new virtual chapter for veterans. In addition to his advocacy, he works as part of a hazard mitigation team, volunteers with the Red Cross, and has a wife and a 2-year-old son — who both motivates Schible to persist through his hearing damage and makes what he’s lost all the more acute.

“I get scared a lot because now that I have an adorable little guy in this world — I don’t want to miss out,” he said. “And I feel like as he gets older, the more of my hearing is going to virtually deteriorate. And so I’m going to miss a lot of the things that he says. Those are some of the things that I worry about later in life.”

For more information and support, veterans can visit the Hearing Loss Association of America’s Veterans Across America Virtual Chapter.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.