New organ donation technique challenges line between life and death

A new organ donation technique can recover more organs from each donor, and organs that are less likely to fail. But some doctors say it’s unethical.

Listen 10:02

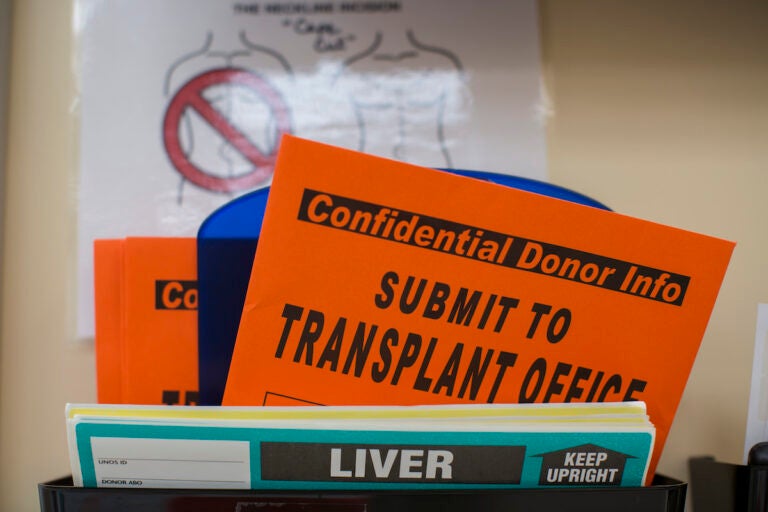

This Friday, Feb. 21, 2014 photo shows organ donation paperwork at Mid-America Transplant Services in St. Louis. (AP Photo/Whitney Curtis)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In 2021, Navy officer Tony Donatelli felt a pain in his legs that got worse.

He was diagnosed with AL amyloidosis, a rare disease where abnormal proteins gather in the organs. At 40 years old, he went from being a fit, active-duty Navy officer to sometimes not being able to walk around a hospital room five times.

“I was decomposing,” he said. “I was losing muscle. I was getting weaker.”

Donatelli needed a heart, liver, and kidney transplant to live, and he needed all three organs at the same time.

People who need organ donations sometimes wait for months or years. Some even die while waiting for an organ transplant.

But, Donatelli got those three organs, thanks to a donor and a new technique that can recover more organs from each donor, and organs that are less likely to fail.

However, the new procedure is controversial, even among doctors. The American College of Physicians, the second largest professional group for doctors in the U.S. declared this procedure unethical, and said it should not be allowed in the U.S, because, “nature is not taking its course, but rather medicine is intervening to ensure death.”

Right now, most organ donations come from people whom doctors declare brain dead, meaning they have no brain function. A surgical team takes a donor to an operating room, opens up their chest, and takes the organs out.

Later, doctors also started to collect organs from people who died because their hearts stopped. Doctors declare that someone is dead, wait a while to confirm that the person’s heart will not start again on its own. Then, they could recover lungs, livers, and kidneys, but not hearts.

Doctors used to think that technique didn’t work on hearts, because if a heart had stopped without oxygen for too long, it would be irreversibly damaged.

But the new procedure that saved Tony Donatelli’s life — NRP, or normothermic regional perfusion — changes things.

Subscribe to The Pulse

In these cases, a patient’s heart has stopped, and the damage is so serious that doctors and families agree there is no meaningful recovery. A patient could not live without always being hooked up to machines. Doctors declare the patient dead, wait to make sure the heart will not start on its own. Then, they can use machines to pump blood back into the heart and use a clamp to make sure none of that blood reaches the brain. Then they can recover the heart to be transplanted.

“These hearts are not irreversibly injured,” said heart surgeon Ashish Shah. “You can bring them back, reanimate them. You can actually use them in transplant. They still work a year or more later and work great.”

Shah, chair of cardiac surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, said there are not enough organs to meet the demand for people who need them to survive, and this new technique could change the field. It adds a new group of potential donors. It means that doctors can check to see how the vital organs would perform before taking them. And doctors can recover more organs at a time because the blood keeps pumping.

The problem with this procedure is that in the U.S., only a dead person can donate their vital organs. With this new procedure, doctors pump blood back into a patient’s heart after they have died — and even though there is a clamp to make sure none of the blood reaches the brain — the heart does start beating again.

That means the patient is no longer dead, argues Matthew DeCamp, bioethicist and physician at the University of Colorado.

“It invalidates the prior determination of death,” he said.

He helped write a paper for the American College of Physicians explaining their position against the procedure.

DeCamp said imagine a patient’s heart stops in a hospital, a medical team puts them on life support, the person’s heart starts beating, and they start breathing again. He said that brings a patient back to life, and it is no different in the context of the new organ donation procedure.

He said that doctors who are in favor of this organ donation technique say even if, by some accident, blood flowed to these patient’s brains again, their chances of recovering brain function are very, very slim.

“But to say that they’re slim is not to say that they’re zero. And so, what that statement really is — is an implicit judgment about a quality of life worth living.”

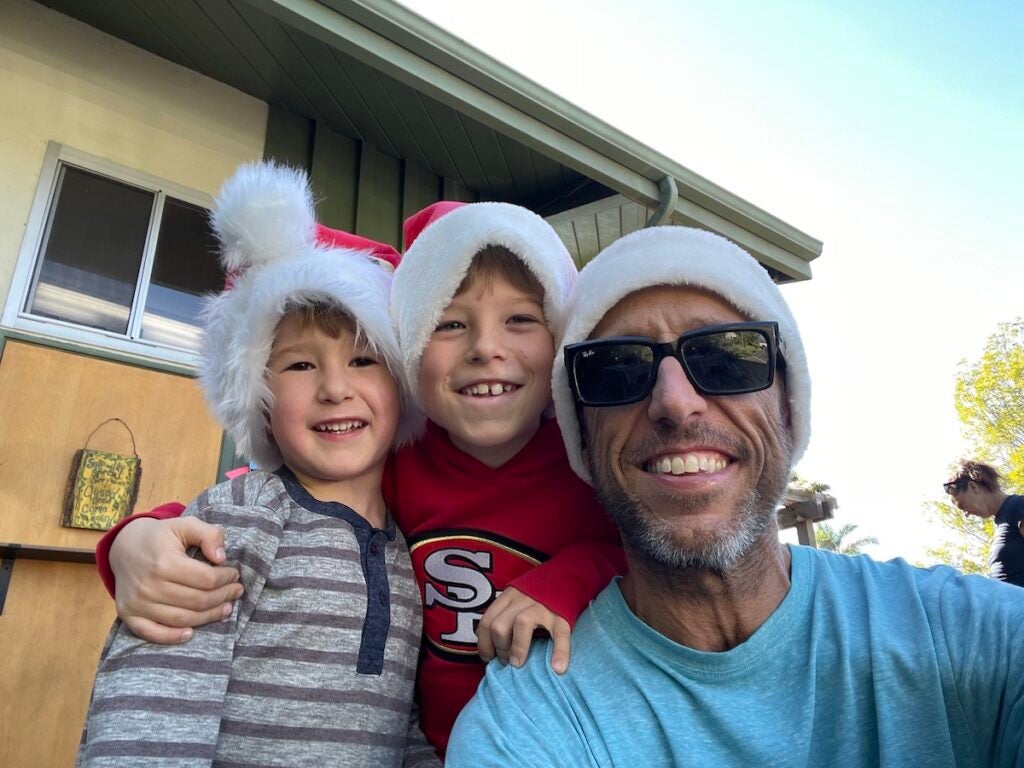

Rob and Katherine Kerr know what it is like to make a judgment like that.

Their third son, Jared Kerr, was diagnosed with a rare genetic brain disorder called metachromatic leukodystrophy when he was 2 years old.

Patients gradually lose the ability to walk or speak. Most do not live past childhood.

When Jared was three years old, he got a stem cell transplant from a donor in North Carolina. That helped him live longer. But his father Rob says it did not mean he recovered.

“He wore a diaper. He was fed by a tube … so he never ate by mouth,” Rob said. “He went from … walking and talking and stuff to where he couldn’t even sit up on his own … he was in a hospital bed in a wheelchair and everything for 14 years.”

Rob and Katherine took care of Jared at home, with around the clock care. They had all kinds of medical equipment, and a nurse to take Jared to school.

In 2021, when Jared was 17, he caught a cold, and he did not get better. He went to the hospital and had to be put on a ventilator three times. But despite that, his lungs started failing. His doctors told Rob and Katherine that Jared would need to breathe through a tube for the foreseeable future.

“Then he’s gonna be on … these machines forever,” Rob said. “Throughout our years of being with handicapped kids and seeing other stories, we knew that that was going to be a very, very difficult life for him. So, we decided to … let him go.”

They took Jared off the ventilator. Jared died in July 2021 at the age of 17.

Rob and Katherine never forgot the stem cell transplant Jared got at the age of three.

“He was gifted the cord blood that saved his life or extended his life to 17 years old when his life expectancy was 5 years old,” Katherine said. “We always wanted to give back.”

Using NRP, the new organ donation technique, Jared donated his heart and kidneys. Rob says that for him and Katherine, even if Jared’s heart was beating again inside his body, his lungs would not have recovered. That’s why they agreed to take Jared off life support.

“The way I looked at it is: Your ultimate goal is to restart the heart in someone else,” he said. “Knowing Jared helped these other people is what helps me get up every day and keep rolling.”

He says they are in touch with the person who now has Jared’s heart, who had a heart problem since she was 10 years old.

“She couldn’t even walk across the living room without getting out of breath, couldn’t even climb the steps, and because of Jared’s amazing donation, she just finished her first 10k.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.