New blood test could indicate long-term severity of concussions

Listen

Over the past 15 years, scientists and physicians have come to realize that concussions are very serious injuries. In fact, about 20 percent of people who suffer a concussion go on to have long term cognitive impairment. Considering there are at least two million concussions per year in the U.S., 20 percent means 400,000 people – that’s a lot of brain damage.

We know concussions are a big deal, but how exactly do we diagnose one? The things commonly associated with concussions – blacking out or seeing stars – only happen in a fraction of cases. You can’t feel your brain cells dying. So I wanted to find out exactly how we go about diagnosing this condition. I spoke with Dr. Douglas Smith, Director of the Center for Brain Injury and Repair at the University of Pennsylvania, who walked me through the process. As I found out, it’s still a rather primitive ordeal. Dr. Smith states, “Currently, (there’s) what we call the sideline test. You would have taken a baseline test at some point.”

So if you were a person at high risk for concussion, like an athlete or soldier, you would have taken a test before anything happened – usually consisting of a few simple questions. And these tests, adds Dr. Smith, “often look at things like what we call processing speed, how quickly you can think. Or memory, whether you can retain something that was just told to you.” And then if you get hit, you take the test again. Dr. Smith continues, “When you take the test again, your new score is going to be compared to that.” If you performed worse than your baseline, Smith notes, “you go to the emergency room. And even currently, you’re basically being watched.”

Considering the fact that we all agree concussions are a major public health concern, it’s amazing that we’re still relying on coaches to diagnose them using pretty primitive tools. I mean, this is all so subjective. And most of us haven’t even had a baseline test in the first place. But even if you did, according to Dr. Robert Siman, research professor of Neurosurgery at Penn, “they can be manipulated by the individuals or interpreted in varying ways by those giving the test.” He adds, “There’s clear opportunity for an objective, quantitative measure that takes the decision-making out of the hand of the athlete, and the trainer and the coaching staff.”

Is there a better way to diagnose concussions? Is there a better way to tell who will end up in the 20 percent with long term damage and who will be just fine? Dr. Siman and Dr. Smith believe the answer just might be a protein they’ve discovered, called SNTF. That’s short for calpain-cleaved αII-spectrin N-terminal fragment. How could this tiny protein potentially help diagnose millions of concussion sufferers per year? Understanding that requires an understanding of the protein’s function. “It’s a fragment of a protein that is normally a part of the structural support of the axon,” states Dr. Siman.

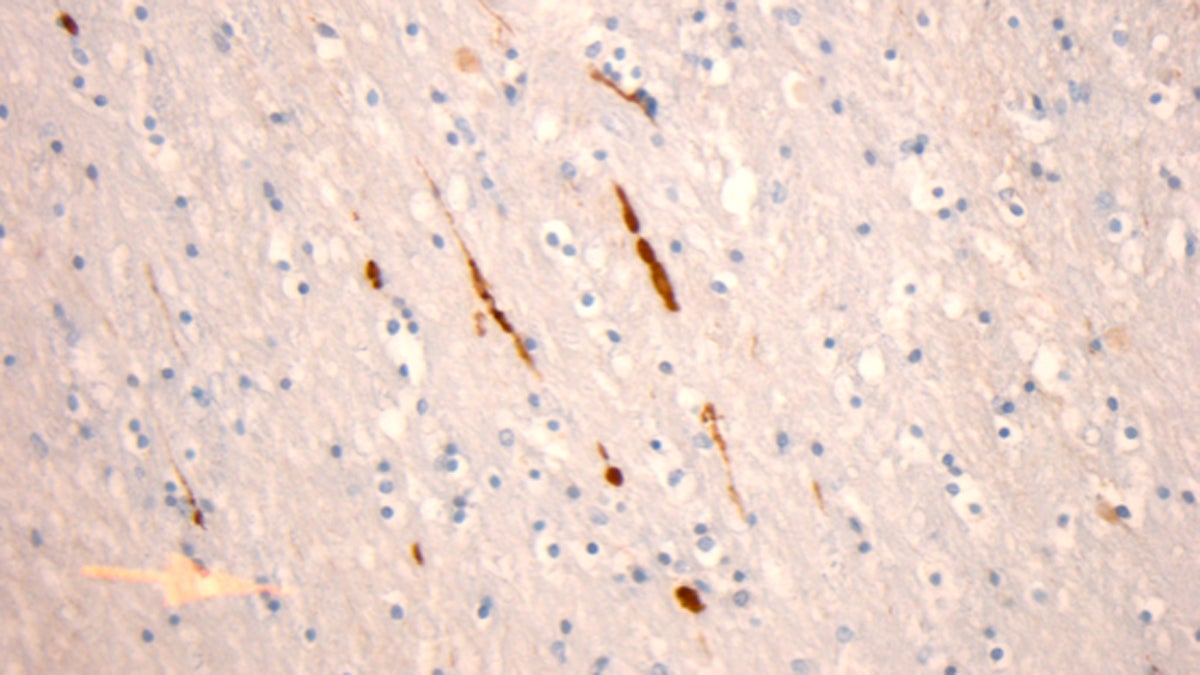

Your brain is made up of nerve fibers. And there are proteins that create the structural support inside those nerve fibers. So if the nerve fiber is a tent, these proteins are the tentpoles. When you get a concussion, and your brain bangs around the inside of your skull, the nerve fiber gets damaged and those structural proteins get broken. They literally break in half. The tent collapses and dies, and that broken half tentpole is SNTF. Dr. Siman notes, “This structural protein gets cleaved in half, and one of the halves of this protein, that’s normally not found in axons, starts to accumulate within axons.”

And so this cellular rubble, all these broken tentpoles, start to pile up in the brain as nerve fibers collapse and die. It’s a strange process that continues long after the moment of injury, and is kind of kept going by certain enzymes that run amok inside the cell. But regardless, once the levels get high enough, SNTF starts leaking into the bloodstream. “And that’s the protein we find becomes measurably increased in the blood.” concludes Dr. Siman.

And the good thing about a protein that leaks into the blood is that it can be measured. In other words SNTF could be the first objective blood test for brain injury. Dr. Smith notes, “If we see the proteins that should be in those axons appear in the blood, that means those axons died.”

In 2013, they tested the concept on patients coming into the Emergency Department after head injuries and their results were promising. In 2014 they collaborated with Swedish researchers who had access to some pretty amazing research subjects. “All 288 players in the top professional ice hockey league in Sweden agreed to participate in this study,” notes Siman. They measured SNTF levels in the players before the season began. Then they took serial measurements of SNTF if and when any player got hit during the season. And, amazingly, they found that SNTF levels did in fact correlate with concussion severity.

Siman states, “Players who suffered a concussion and had their post concussion symptoms resolve within a few days had no difference in their blood levels of SNTF. But for that subset of players that had persisting post concussion symptoms, that required that they be withheld from play for six days or longer, they had measurable and statistically significant blood elevations in SNTF.” In other words, the test was able to distinguish between bad concussions and not so bad concussions.

Siman adds, “And so SNTF blood levels were a prognostic marker in that within hours of a player suffering a concussion, their blood levels of SNTF could be used to predict which of those concussed hockey players were going to go on to suffer long term post concussion symptoms.”

More brain damage, more SNTF leaking out. It’s a simple concept, but the implications are huge. Siman states, “It’s an admittedly small study, but it’s the first evidence that a marker could be measured in the bloodstream on the day of a concussion that could distinguish between those individuals who are going to be OK and those who are not.”

Right now, they are the only lab capable of measuring SNTF, but Dr. Siman has patented the test and is in the process of developing it. But even so, there’s still a lot of work to be done. Because the fact is, even if we do diagnose a concussion, we still don’t have any great treatment for it. “Exactly how to rehabilitate someone who has suffered a damaging concussion is something that’s never been defined,” notes Dr. Siman.

But Siman’s hope is that an objective test like SNTF could help researchers investigate new treatment strategies. So what does this all mean in the big picture? I asked Anthony Kontos, the assistant research director at the UPMC sports concussion center. He emphasized that while their results so far were promising, their sample size is small and more research is needed. Additionally, he noted, “Just like with any disease or any injury, we typically don’t rely on a single test or single blood biomarker. For example for heart disease they do an assay test of multiple markers, and I think that’s where these blood biomarkers will help us out down the road as providing a potential spectrum of information for different subtypes of the injury. And SNTF may fit into one of those subtypes or one particular approach across a larger assay of multiple blood biomarker tests.”

And to be fair, there are ongoing studies looking at other blood markers, as well as better imaging that would allow doctors to actually “see” concussion damage. So regardless of which method ends up on top, the race is certainly on to find a 21st century measure for a 21st century injury.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.