‘Americanitis’ and the perils of life in the fast lane

Listen

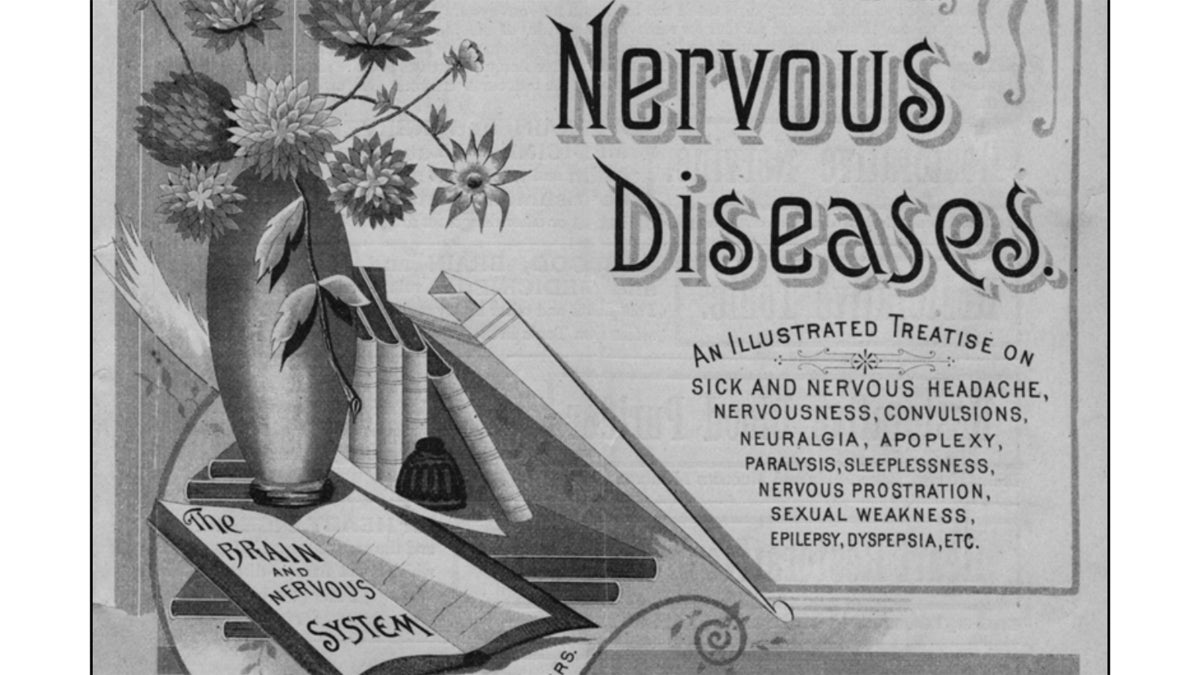

Pharmaceutical companies published booklets like this in the late 1800s as a way of getting people to self-diagnosis with neurasthenia as the first step towards self-medicating with proprietary medicines. (Courtesy of John W. Hartman Center for Sales

Are you feeling stressed out and sluggish? Worried about your work-life balance? Are you not sleeping well, can’t concentrate, have frequent stomach troubles, and aches and pain?

In the 19th century, you might have been diagnosed with Neurasthenia – a condition which was defined by neurologist George Beard.

“The condition was predicated on the idea that our bodies run on nervous energy,” explained history professor David Schuster, who has written a new book called “Neurasthenic Nation.”

“This was a popular idea in late 19th century – the time of Edison – and it was thought that we eat food, which is digested into energy, and our nervous systems transport the energy to our organs. And when our bodies ran low on this energy, it could cause all kinds of mental and physical health problems.”

The decades after the civil war were a time of rapid change for the nation. Cities were industrializing and growing, the railroad was expanding, the invention of the telephone was around the corner, the stock ticker was about to go live. Americans, it seemed, were doing more than ever before, and were growing concerned about the impact of life in the fast lane on their health.

Physician and philosopher William James soon dubbed this malaise “Americanitis,” which was part commentary on how fascinated Americans had become with their health, and part humble brag that America was more modern than any other nation. People were paying the price for being so advanced.

“It’s almost like if you had Neurasthenia, you were working hard at something, you worked yourself into sickness, and you needed to recover, take some time off, get back into the rat race,” said Schuster.

Neurasthenia was not just for entrepreneurs and businessmen, though – it was closely associated with artists and creative people. “People who were focused on ideas, used their brains to excess, felt strongly for things, that made them more susceptible,” said Schuster.

The treatment for Neurasthenia was different for men and women. Women were told they needed a rest cure – six to eight weeks of bed rest, sometimes even with bed pans so they never had to get up.

For men, treatment was far more exciting.

“Men were told ‘go out West and rediscover your cowboy roots,’ it was thought that living close to nature restored the body’s vitality.”

Neurasthenia fell out of favor with the medical profession in the early 20th century, as science discovered the impact of hormones and vitamins, and as Sigmund Freud introduced a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between body and mind.

But David Schuster says the concerns framed by the Neurasthenia diagnosis are alive and well today.

“Back then, people were concerned about the move from farm to the city, from the calm life in the country, to the artificial life in a city. Now it’s looking at your smart phone rather than the people at your dinner table.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.